Chapter 23 | False Alarms | A Dash From Diamond City

The bottom and surroundings of the eminence afforded plenty of cover, and the fugitives pushed on in and out among dense patches of low growth, and, leading their sure-footed little ponies, they climbed over and around piles and masses of stone that would have been difficulties even to mules, while twice over West scaled a slope so as to carefully look down and backward at the enemy.

This he was able to do unseen, and came down again to report that the patrol was still making for the kopje as if for rest, but that their movements were too careless and deliberate for those of an enemy in pursuit.

The far side of the pile of granite and ironstone was reached in safety, placing the fugitives about a quarter of a mile from the Boers in a direct line, but quite a mile of intricate climbing if measured by the distance round; and they paused in a green patch full of refreshing beauty, being a wide ravine stretching up into the height, and with a bubbling stream of water running outward and inviting the ponies at once to take their fill.

“This settles it at once!” said Ingleborough, letting his bridle fall upon his mount’s neck.

“Yes; we can go well in yonder, leading the ponies along the bed of the stream. There is plenty of cover to hide half a regiment.”

“Of Boers,” said Ingleborough shortly. “It will not do for us.”

“Why?” said West, staring. “We can hide there till they have gone.”

“My dear boy,” said Ingleborough; “can’t you see? The beggars evidently know this place, and are making for it on account of the water. We saw none on the other side.”

“Very well,” said West sharply; “let’s ride off, and keep the hill between us and them.”

“Too late!” said Ingleborough. “This way; come on!”

For as he spoke there was the loud beating noise of many hoofs, indicating that the whole or a portion of the commando was coming at a gallop round the opposite side of the kopje from that by which the fugitives had come; and to have started then would have meant a gallop in full sight of a large body of men ready to deliver a rifle-fire of which they would have had to run the gauntlet.

“We’re entering another trap,” said West bitterly, as they led their reluctant ponies along the bed of the stream, fortunately for them too stony for any discoloration to be borne down to show the keen-eyed Boers that someone had passed that way, and at the same time yielding no impress of the footprints of man or beast.

As far as the fugitives could see, the ravine went in a devious course a couple of hundred yards into the eminence, but, as it proved, nearly across to the other side. It was darkened by overhanging trees and creepers, which found a hold in every ledge or crack of the almost perpendicular sides, and grew darker and darker at every score of yards; but the echoing rocks gave them full notice of what was going on near the entrance, the voices of the Boers and the splashing noise of their horses’ feet coming with many repetitions to drown any sound made by their own.

“It isn’t a bad place!” said Ingleborough, as they hurried on, with the ravine growing more narrow and the sides coming more sharply down into the water. “It strikes me that we shall find the water comes out of some cave.”

Five minutes later Ingleborough proved to be quite correct, for they paused at a rugged archway between piled-up fern-hung blocks, out of which the water rushed in a fairly large volume, but not knee-deep; and, upon leaving his horse with his comrade and boldly wading  in, West found that the cave expanded as soon as the entrance was passed, so that the spring ran outward along a narrow stony bed, and on either side there was a bed of sand of considerable width.

in, West found that the cave expanded as soon as the entrance was passed, so that the spring ran outward along a narrow stony bed, and on either side there was a bed of sand of considerable width.

“Come along!” said West. “The water gets shallower, and there is a dry place on either side.”

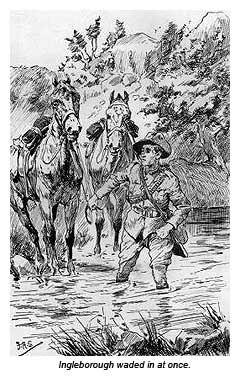

Ingleborough waded in at once, but unfortunately the ponies shrank from following, and hung back from the reins, one of them uttering a loud snort, which was repeated from the interior so loudly that the second animal reared up wildly and endeavoured to break away.

West dashed back though directly and relieved his companion of one of the refractory beasts, when by means of a good deal of coaxing and patting they were finally got along for some yards and out onto the sandy side, where they whinnied out their satisfaction and recovered their confidence sufficiently to step towards the running waters and resume their interrupted drink.

“Rifles!” said Ingleborough shortly, when West unslung his and stood ready, following his companion’s example as he stood in the darkness with his piece pointing out at the bright stream with its mossy and fern-hung framing.

“Did you hear anyone coming?” whispered West.

“No, but they must have heard our ponies and be coming on,” was the reply.

“Let them come; we can keep the whole gang at bay from here!”

But five minutes’ watching and listening proved that they had not been heard, for the Boers were too busy watering their horses, the voices of the men and the splashings and tramplings of the beasts coming in reverberations right along the natural speaking-tube, to strike clearly upon the listeners’ ears.

Three several times the fugitives stood on guard with rifles cocked, ready to make a determined effort to defend their post of vantage, for the voices came nearer and nearer, and splashing sounds indicated movements out towards the mouth of the ravine; but just when their nerves were strained to the utmost, and they watched with starting eyes a corner round which the enemy would have to turn to bring them within range, the talking and splashing died out, and they simultaneously uttered a sigh of relief.

“I couldn’t bear much of this, Ingle,” said West, at last. “I half think that I would rather have them come on so that we could get into the excitement of a fight.”

“I don’t half think so, lad; I do quite,” replied Ingleborough.

“But you don’t want to fight?”

“Of course not; I don’t want to feel that I’ve killed anybody; but at the same time I’d rather kill several Boers than they should kill me. However, I hope they will not attack us, for if they do I mean to shoot as straight as I can and as often as is necessary. What do you say?”

West was silent for a few moments, during which he seemed to be thinking out the position. At last he spoke: “I have never given the Boers any reason for trying to destroy my life, my only crime being that I am English. So, as life is very sweet and I want to live as long as I can, I shall do as you do till they get disheartened, for I don’t see how they can get at us, and—”

“Here, quick, lad!” whispered Ingleborough, swinging round. “We’re attacked from behind!”

West followed his example, feeling fully convinced that the Boers had after all seen them seek refuge in the cavern, and had taken advantage of their knowledge of the place to creep through some tunnel which led in from the other side, for there was a strange scuffling and rustling sound a little way in, where it was quite dark. With rifles pointed towards the spot and with fingers on triggers, the two friends waited anxiously for some further development, so as to avoid firing blindly into the cavern without injury to the enemy while leaving themselves unloaded when their foes rushed on.

“Can’t be Boers!” said Ingleborough, at the end of a minute, during which the noise went on; “it’s wild beasts of some kind.”

“Lions,” suggested West.

“Oh no; they’d go about as softly as cats! More like a pack of hyaenas trying to get up their courage for a charge!”

“If we fired and stood on one side they’d rush out!” replied West.

“Yes,” said Ingleborough grimly; “and the Boers would rush in to see what was the matter. That wouldn’t do, for it’s evident that they don’t know we’re here.”

“But we must do something, or they’ll injure the horses! Why!” cried West excitedly; “it must be that they’ve pulled the poor beasts down and are devouring them.”

“Without our little Basutos making a kick for life? Nonsense! They’d squeal and kick and rush out. Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha!”

To West’s astonishment his companion burst into a prolonged fit of gentle laughter.

“Here, come along!” he said. “Of all the larky beggars! Here, you two ruffians, stow that, or you’ll smash up those saddles!”

Ingleborough dashed in, followed at once by West, and as they got in further from the cave’s mouth they dimly saw their mounts spring up from having a good roll and wriggle upon the soft dry sand to rest their spines and get rid of the larvae of some worrying pernicious horse-fly.

The moment the two ponies were on all-fours they gave themselves a vigorous shake, and then whinnied softly and advanced to their riders with out-stretched necks, expectant of a piece of bread or some other delicacy with which they had been petted from time to time.

“Why, you larky little rascals!” cried Ingleborough, patting the two beasts affectionately; “what do you mean by frightening us out of our seven senses? I mean frightening me, for you weren’t scared a bit—eh, West?”

“Frightened? It was horrible! I can understand now why the Boers can’t bear being attacked from behind!”

“Of course! I say, though, no wonder children are afraid of being in the dark.” He turned to the ponies, and said: “Look here, my lads, I suppose you don’t understand me, but if you could take my advice you’d lie down to have a good rest. It would do you both good, and if the firing did begin you’d escape being hit.”

To this one of the ponies whinnied softly, and then moved gently to its companion’s side, head to tail, bared its big teeth as if to bite, and began to draw them along the lower part of the other’s spine, beginning at the root of the tail and rasping away right up to the saddle, while the operatee stretched out its neck and set to work in the same way upon the operator, upon the give-and-take principle, both animals grunting softly and uttering low sounds that could only be compared to bleats or purrs.

“They say there’s nothing so pleasant in life as scratching where you itch,” said West, laughing. “My word! They do seem to enjoy it.”

“Poor beggars, yes!” replied Ingleborough. “I believe there’s no country in the world where animals are more tortured by flies than in Africa. The wretched insects plunge in that sharp instrument of theirs, pierce the skin, and leave an egg underneath; the warmth of the body hatches it into what we fishing boys called a gentle, and that white maggot goes on eating and growing under the poor animal’s coat, living on hot meat always till it is full-grown, when its skin dries up and turns reddish-brown, and it lies still for a bit, before changing into a fly, which escapes from the hole in the skin it has eaten and flits away to go and torture more animals.”

“And not only horses, but other animals!” said West quietly.

“Horses only? Oh no; the bullocks get them terribly, and the various kinds of antelopes as well. I’ve seen skins taken off blesboks and wildebeestes full of holes. And there you are, my lad; that’s a lecture on natural history.”

“Given in the queerest place and at the strangest time a lecture was ever given anywhere,” said West.

“It is very horrible, though, for the animals to be tortured so!”

“Yes,” said Ingleborough thoughtfully; “but the flies must enjoy themselves wonderfully. They must have what people in England call a high old time, and—eh? What’s the matter?”

“Be ready!” whispered West. “Someone coming; there’s no mistake now!”