Chapter 22 | But All's Well | The Young Castellan

Lady Royland was surrounded by the trembling women of the household, who, scared by the firing, had sought her to find comfort and relief.

“What! the ten men safely brought in!” she cried, as her son hastened to tell his tidings. “And no one hurt?”

“No one on our side, mother,” said Roy, meaningly; “I cannot answer for those across the moat.”

“Our ten poor fellows here in safety,” cried Lady Royland, once again. “Oh, Roy, my boy, this is good news indeed! But you must be faint and exhausted. Come in the dining-room. I have something ready for you.—There, you have nothing to fear now,” she said, addressing the women; “but one of you had better go and tell Master Pawson that we are ready to sup.”

The women went out, some of them still trembling and hysterical, and all white and scared of aspect.

As soon as the door was closed, Lady Royland caught her son’s hand.

“Eight of us women,” she said, with a forced laugh: “eight, and of no use whatever; only ready to huddle together like so many sheep scared by some little dog; when, if we were men, we could be of so much help. There, come along; you look quite white. You are doing too much. For my sake, take care.”

Roy nodded and smiled, and followed his mother into the dining-room, where with loving care she had prepared everything for him, and made it attractive and tempting, so that it should be a relief to the harsh realities of the warlike preparations with which the boy was now mixed up.

“You must eat a good supper, Roy, and then go and have a long night’s rest.”

“Impossible, mother,” he said, faintly; “must go and visit the men’s posts from time to time.”

“No,” said Lady Royland, firmly, as she unbuckled her son’s sword-belt, and laid it and the heavy weapon upon a couch.

There was a tap at the door directly after, and one of the maids came back.

“If you please, my lady, I’ve been knocking ever so long at Master Pawson’s door, and he doesn’t answer. We think he has gone to bed.”

“Surely not. He must be in the upper chamber arranging about the things being removed.”

“No, my lady; that was all done a long time ago. It was finished before the fighting began, for he wouldn’t have nothing but his bed and washstand brought down. The men had to take most of the other things right down in the black cellar place underneath, so as to clear the chamber.”

“But did you ask the men on guard if they had seen him?”

“Yes, my lady; they say he shut himself up in his room.”

“That will do. Never mind,” said Lady Royland, dismissing the maid.—“Now, Roy, I am going to keep you company, and—oh, my boy! what is it? Ah! You are hurt!”

She flew to his side, and with trembling hands began to tear open his doublet, but he checked her.

“No, no, mother, I am not—indeed!”

“Then what is it? You are white and trembling, and your forehead is all wet.”

“Yes, it has come over like this,” he faltered, “all since the fight and getting the men in through the sally-port.”

“But you must have been hurt without knowing it.”

“No, no,” he moaned, as he sank back in the chair, and covered his face with his hands.

“Roy, my boy, speak out. Tell me. What is the matter?”

“I didn’t mean to speak a word, mother,” he groaned; “but I can’t keep it back.”

“Yes; speak, speak,” she said, tenderly, as she sank upon her knees by his side, and drew his head to her breast.

“Ah!” he sighed, restfully, as he flung his arms about her neck. “I can speak now. I should have fought it all back; but when I came in here, and saw all those frightened women, and you spoke as you did about being so helpless, it was too much for me.”

“Oh, nonsense!” she cried, soothingly. “Why should their—our—foolish weakness affect you, my own brave boy?”

“No, no, mother,” he cried; “don’t—don’t speak like that. You hurt me more.”

“Hurt you?” she said, in surprise.

“Yes, yes,” he cried, excitedly. “You don’t know; but you must know—you shall know. I’m not brave. I’m a miserable coward.”

“Roy! Shame upon you!” cried Lady Royland, reproachfully.

“Yes, shame upon me,” said the lad, bitterly; “but I can’t help it. I have tried so hard; but I feel such a poor weak boy—a mere impostor, trying to lord it over all these men.”

“Indeed!” said Lady Royland, gravely. “Yes? Go on.”

“I know they must see through me, from Ben down to the youngest farm hand. They’re very good and kind and obedient because I’m your son; but they, big strong fellows as they are, must laugh at me in their sleeves.”

“Ah! you feel that?” said Lady Royland.

“Yes, I feel what a poor, girlish, weak thing I am, and that all this is too much for me. Mother, if it were not for you and for very shame, I believe I should run away.”

“Go on, Roy,” sand Lady Royland; and her sweet, deep voice seemed to draw the most hidden thoughts of his breast to his lips.

“Yes, I must go on,” he cried, excitedly. “I hid it all when I went to face that officer, who saw through me in spite of my bragging words, and laughed; and in the wild excitement of listening to-night to the troopers closing us in and trying to capture those poor fellows, I did not feel anything like fear; but now it is all over and they are safe, I am—I am—oh, mother! it is madness—it is absurd for me, such a mere boy, to go on pretending to command here, with all this awful responsibility of the fighting that must come soon. I know that I can’t bear it—that I must break down—that I have broken down. I can’t go on with it; I’m far too young. Only a boy, you see, and I feel now more like a girl, for I believe I could lie down and cry at the thought of the wounds and death and horrors to come. Oh, mother, mother! I’m only a poor pitiful coward after all.”

“God send our poor distressed country a hundred thousand of such poor pitiful cowards to uphold the right,” said Lady Royland, softly, as she drew her son more tightly to her swelling breast. “Hush, hush, my boy! it is your mother speaks. There, rest here as you used to rest when you were the tiny little fellow whose newly opened eyes began to know me, whose pink hands felt upward to touch my face. You a coward! Why, my darling, can you not understand?”

“Yes, I understand,” he groaned, as he clung to her, “that it is my own dear mother trying to speak comfort to me in my degradation and shame. Mother, mother! I would not have believed I was such a pitiful cur as this.”

“No,” she said, softly; “I am speaking truth. You do not understand that after the work and care of all this terrible time of preparation, ending in the great demands made upon you to-day, the strain has been greater than your young nature can bear. Bend the finest sword too far, Roy, and it will break. You are overdone—worn-out. It is not as you think.”

“Ah! it is you who do not know, mother,” he said, bitterly. “I am not fit to lead.”

“Indeed! you think so?” she said, pressing her lips to his wet, cold brow. “You say this because you look forward with horror to the bloodshed to come.”

“Yes; it is dreadful. I was so helpless to-night, and I shall be losing men through my ignorance.”

“Helpless to-night? But you beat the enemy off.”

“No, no—Ben Martlet’s doing from beginning to end.”

“Perhaps. The work of an old trained man of war, who has ridden to the fight a score of times with your father, and now your brave father’s son’s right-hand—a man who worships you, and who told me only to-day, with the tears in his eyes, how proud he was of that gallant boy—of you.”

“Ben said that—of me?”

“Yes, my boy; and do you think with all his experience he cannot read you through and through?”

“No, mother, he can’t—he can’t,” said the lad, despondently; “no one can know me as I do.”

“Poor child!” she said, fondly, as she caressed him; “what a piece of vanity is this! A boy of seventeen thinking he knows himself by heart. Out upon you, Roy, for a conceited coxcomb! Why, we all know you better than you know yourself; and surely I ought to be the best judge of what you are.”

“No,” said Roy, angrily; “you only spoil me.”

“Indeed! then I shall go on, and still spoil you in this same way, and keep you the coward that you are.”

“Mother!” he cried, reproachfully; “and with all this terrible responsibility rising like a dense black cloud before my eyes.”

“Yes, Roy, because it is night now, and black night too, in your weary brain. Ah! my boy, and to how many in this world is it the same black night. But the hours glide on, the day dawns, and the glorious sun rises again to pierce the thick cloud of darkness, and brighten the gloomy places of the earth. Just as hope and youth and your natural vigour will chase away your black cloud, after the brain has been fallow for a few hours, and you have had your rest.”

“No, no, no,” he groaned; “you cannot tell.”

“I can tell you, Roy,” she said, softly; “and I can tell you, too, that your father is just such another coward as his son.”

“My father!” cried Roy, springing to his feet, flushed and excited. “My father is the bravest, truest man who ever served the king.”

“Amen to that, my boy!” said Lady Royland, proudly; “but do you think, Roy, that our bravest soldiers, our greatest warriors, have been men made of iron—cruel, heartless beings, without a thought of the terrible responsibilities of their positions, without a care for the sufferings of the men they lead? I believe it never has been so, and never will. Come, my darling,” she continued, clinging to his hands, and drawing herself to her feet—“come here for a little while. There,” she said, softly, taking the sword from the couch; “your blade is resting for a while; why should not you? Yes: I wish it; lie right down—for a little while—before we sup. Ah, that is better!”

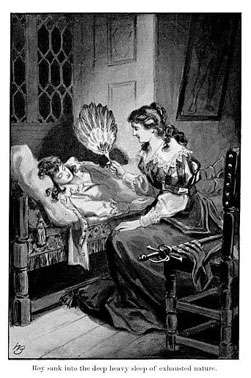

Utterly exhausted now, Roy yielded to her loving hands, and sank back upon the soft couch with a weary sigh; while, as he stretched himself out, she knelt by his side, and tenderly wiped his brow before passing her hands over his face, laying his long hair back over the pillow, and at every touch seeming to bring calm to the weary throbbing brain.

After a few minutes he began to mutter incoherently, and Lady Royland leaned back to reach a feather-fan from a side-table, and then softly wafted the air to and fro  till the words began to grow more broken, and at last ceased, as the boy uttered a low, weary sigh, his breath grew more regular, and he sank into the deep heavy sleep of exhausted nature.

till the words began to grow more broken, and at last ceased, as the boy uttered a low, weary sigh, his breath grew more regular, and he sank into the deep heavy sleep of exhausted nature.

Then the fan dropped from Lady Royland’s hand, and she rose to cross the room softly, and with a line draw up the casement of the narrow slit of a window which looked down upon the moat, for the night wind came fresher there than from the main windows looking upon the garden court.

Softly returning, she bent down, and with the lightest of fingers untied the collar of her son’s doublet and linen shirt, before bending lower, with her long curls drooping round his face, till she could kiss his brow, no longer dank and chilly, but softly, naturally warm.

This before sinking upon her knees to watch by his side for the remainder of the night; and as she knelt her lips parted to murmur—

“God save the king—my husband—and our own brave boy!”

A moment later, as if it were an answer to her prayer, a voice, softened by the distance, was heard from the ramparts somewhere above uttering the familiar reply to a challenge—

“All’s well!”