Chapter 18 | A Test of Manhood | Diamond Dyke

Dyke uttered a cry of horror as he ran to the bedside and sank upon his knees, gazing wildly in his brother’s dark, thin face, with its wild eyes, in which was no sign of recognition, though Emson kept on muttering in a low voice.

“Joe—Joe, old fellow, don’t you know me?” There was no reply, and in his agony of spirit Dyke caught his burning, dry hand, and pressed it.

“Speak to me!” he cried. “How long have you been ill? What is it, Joe? Tell me. What am I to do?”

No answer; but the muttering went on, and Dyke turned to the Kaffir woman. “How long has he been ill?”

“Baas Joe go die,” said the woman, nodding her head.

“No, no; he will be better soon. When was he taken ill?”

“Baas Joe go die,” said the woman with horrible persistence. “No eat—no drink—no sleep. Go die.”

“Go away!” cried Dyke wildly. “You are as bad as one of those horrible birds. Get out!”

The woman smiled, for she did not understand a word. The gesture of pointing to the door was sufficient, and she went out, leaving the brothers alone.

“Joe!” cried Dyke wildly. “Can’t you speak to me, old chap? Can’t you tell me what to do? I want to help you, but I am so stupid and ignorant. What can I do?”

The muttering went on, and the big erst strong man slowly rolled his head from side to side, staring away into the past, and sending a chill of horror through the boy.

For a few moments Dyke bowed his head right into his hands, and uttered a low groan of agony, completely overcome by the horror of his position—alone there in that wild place, five or six days’ journey from any one, and hundreds of miles from a doctor, even if he had known where to go.

He broke down, and crouched there by the bedside completely prostrate for a few minutes—not for more. Then the terrible emergency stirred him to action, and he sprang up ready to fight the great danger for his brother’s sake, and determined to face all.

What to do?

He needed no telling what was wrong; his brother was down with one of the terrible African fevers that swept away so many of the whites who braved the dangers of the land, and Dyke knew that he must act at once if the poor fellow’s life was to be saved.

But how? What was he to do?

To get a doctor meant a long, long journey with a wagon. He felt that it would be impossible to make that journey with a horse alone, on account of the necessity for food for himself and steed. But he could not go. If he did, he felt that it would be weeks before he could get back with medical assistance, even if he reached a doctor, and could prevail upon him to come. And in that time Joe, left to the care of this half-savage woman, who had quite made up her mind that her master would die, would be dead indeed.

No: the only chance of saving him was never to leave his side.

Fever! Yes, they had medicine in the house for fever. Quinine—Warburgh drops—and chlorodyne. Which would it be best to give? Dyke hurried to the chest which contained their  valuables and odds and ends, and soon routed out the medicines, deciding at once upon quinine, and mixing a strong dose of that at once, according to the instructions given upon the bottle.

valuables and odds and ends, and soon routed out the medicines, deciding at once upon quinine, and mixing a strong dose of that at once, according to the instructions given upon the bottle.

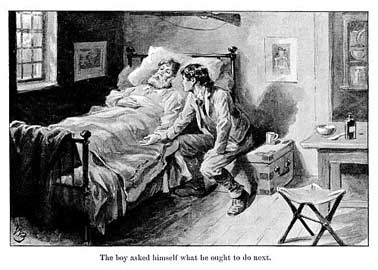

That given, the boy seated himself upon a box by the bed’s head, asking himself what he ought to do next.

He took Emson’s hand again, and felt his pulse, but it only told him what he knew—that there was a terrible fever raging, and the pulsations were quick and heavy through the burning skin.

A sudden thought struck him now. The place was terribly hot, and he hurriedly opened the little window for the breeze to pass through.

There was an alteration in the temperature at once, but he knew that was not enough, and running to the door, he picked up a bucket, and called for Tanta Sal, who came slowly.

“Baas Joe go die.—Jack?”

She pointed away over the plain, and Dyke nodded.

“Yes, Jack is coming. Go, quick! fetch water.”

The woman understood, and taking the bucket, went off at once towards where the cool spring gurgled among the rocks at the kopje.

The feeling of terrible horror and fear attacked Dyke again directly, and he shrank from going to his brother’s side, lest he should see him pass away to leave him alone there in the desert; but a sensation of shame came to displace the fear. It was selfish, he felt; and with a new thought coming, he went to the back of the door, took down the great heavy scissors with which he and Emson had often operated upon the ostrich-feathers, cutting them off short, and leaving the quill stumps in the birds’ skins, where after a time they withered and fell out, giving place to new plumes. Then kneeling down by the head of the rough bed, he began to shear away the thick close locks of hair from about the sick man’s temples, so that the brain might be relieved of some of the terrible heat.

This done, he went to the chest, and got out a couple of handkerchiefs.

His stay in that torrid clime had taught him much, but he had never thought of applying a little physical fact to the purpose he now intended. For he knew that if a bottle or jug of water were surrounded by a wet cloth and kept saturated, either in a draught or in the sun, the great evaporation which went on would cool the water within the vessel.

“And if it will do this,” Dyke thought, “why will it not cool poor Joe’s head?”

He bent down over him, and spoke softly, then loudly; but Emson was perfectly unconscious, and wandering in his delirium, muttering words constantly, but what they were Dyke could not grasp.

In a few minutes Tanta Sal re-appeared with the bucket of cool spring-water.

“Baas Joe go die,” she said, shaking her head as she set it down; and then, without waiting to be told to go, she went round to the back, and began to pile up fuel and fan the expiring fire, before proceeding to make and bake a cake.

Meanwhile, Dyke had been busy enough. He had soaked one of the handkerchiefs in the bucket, and laid it dripping right across Emson’s brow and temples, leaving it there for a few minutes, while he prepared the other. The minutes were not many when he took off the first to find it quite hot, and he replaced it with the other, which became hot in turn, and was changed; and so he kept on for quite an hour, with the result that his brother’s mutterings grew less rapid and loud, so that now and then the boy was able to catch a word here and a word there. All disconnected, but suggestive of the trouble that was on the sick man’s mind, for they were connected with the birds, and his ill-luck, his voice taking quite a despairing tone as he cried:

“No good. Failure, failure—nothing succeeds. It is of no use.”

And then, in quite a piteous tone:

“Poor Dyke! So hard for him.”

This was too much. The tears welled up in the boy’s eyes, but he mastered his emotion, and kept on laying the saturated bandages upon his brother’s brow, watching by him hour after hour, forgetful of everything, till all at once there was a loud, deep barking, and Duke trotted into the house, to come up to the bedside, raise himself up, and begin pawing at the friend he had not seen for so long.

“It’s no good, Duke, old chap,” said Dyke sadly; “he don’t know you. Go and lie down, old man. Go away.”

The dog dropped down on all-fours at once, and quickly sought his favourite place in one corner of the room, seeming to comprehend that he was not wanted there, and evidently understanding the order to lie down.

The coming of the dog was followed by the approach of the wagon, and the lowing of the bullocks as they drew near to their familiar quarters; the cows answered, and Duke leaped up and growled, uttering a low bark, but returned to his corner as soon as bidden.

At first Dyke had felt stunned by the terrible calamity which had overtaken his brother; but first one and then another thing had been suggested to his mind, and the busy action had seemed to clear his brain.

This cool application had certainly had some effect; and as he changed the handkerchief again, he saw plainly enough what he must do next.

Wiping his hands, he sought for paper and pencil, and wrote in a big round hand:

“I came home and found my brother here, at Kopfontein, bad with fever. He does not know me. Pray send to fetch a doctor.”

He folded this, then doubled it small, and tied it up with a piece of string, after directing it to “Herr Hans Morgenstern, at the Store.”

This done, he once more changed the wet handkerchiefs, and went out to find Jack outspanning the cattle, and talking in a loud voice to his wife.

“Jack,” he said, “the baas is very bad. You must go back to Morgenstern’s and take this.”

He handed the tied-up paper to the Kaffir, who took it, turned it over, and then handed it back, looking at his young master in the most helplessly stupid way.

Dyke repeated the order, and pointed toward the direction from which they had come, forcing the letter into Jack’s hand.

It was returned, though, the next moment.

“Jack bring wagon all alone,” he said.

“Yes, I know; but you must go back again. Take plenty of mealies, and go to Morgenstern’s and give him that.”

“Jack bring wagon all alone,” the black said again; and try how Dyke would, he did not seem as if he could make the Kaffir understand.

In despair he turned to Tanta Sal, and in other words bade her tell her husband go back at once; that he might take a horse if he thought he could ride one; if not, he must walk back to Morgenstern’s, and carry the letter, and tell him that the baas was bad.

“Baas Joe go die,” said the woman, nodding her head.

“No, no; he will live if we help,” cried Dyke wildly. “Now, tell Jack he must go back at once, as soon as he has had some mealies.”

“Baas Joe go die,” reiterated the woman.

“Hold your tongue!” roared Dyke angrily. “You understand what I mean. Jack is to go back.—Do you hear, Jack? Go back, and take that to Morgenstern’s.”

The Kaffir and his wife stared at him heavily, with their lower jaws dropped, and after several more efforts, Dyke turned back to the house to continue his ministrations.

“They understand me, both of them,” he cried bitterly; “but he does not want to go, and Tant wants him to stay. What shall I do? What shall I do?”

He changed the handkerchiefs, and rushed out again, but the Kaffirs were invisible; and going round to the back, he found Jack squatted on his heels, eating the hot cake his wife was baking. But though Dyke tried command and entreaty, the pair only listened to him in a dazed kind of way, and it was quite evident that unless he tried violence he would not be able to make the Kaffir stir; while even if he did use force, he felt that Jack would only go a short distance and there remain.

“And I can’t leave here! I can’t leave here!” groaned Dyke; “it would be like saying good-bye to poor Joe for ever.”

Clinging to the faint hope that after he had been well-fed and rested, the Kaffir might be made to fulfil the duty required of him, Dyke went on tending his brother, with the satisfactory result of seeing him drop at last into a troubled sleep, from which, two hours after, he started up to call out for Dyke.

“I’m here, Joe, old chap. Can’t you see me?” said the boy piteously.

“No use: tell him no use. Madness to come. All are dying. Poor Dyke! So hard—so hard.”

Dyke felt his breast swell with emotion, and then came a fresh horror: the evening was drawing on, and he would be alone there with the sick man, watching through the darkness, and ignorant of how to act—what to do. And now the thought of his position, alone there in the great desert, seemed more than he could bear; the loneliness so terrible, that once more, in the midst of the stifling heat, he shuddered and turned cold.