Chapter 27 | Oom Startles His Friends | Diamond Dyke

The days glided peacefully by, with Dyke kept busy enough supplying the larder, especially for his brother’s benefit, and under his treatment the poor fellow grew better.

But so slowly; and he was the mere ghost of his former self when he began to crawl out of the house by the help of a stick, to sit in the shade and watch Dyke as he was busy about the place.

There was very little to vary the monotony of their life. A lion came one night, but did not molest horse or bullock. They had visits, too, from the jackals, but Tanta Sal was right—Jack came no more, and they saw nothing of the Kaffirs who had been his companions, though Dyke found a rough hut and traces of a fire in the patch of forest close to where he went to shoot the guinea-fowl, showing that he must often have been pretty near the Kaffirs’ hiding-place.

In fact, Jack had had a very severe peppering, and felt not the slightest inclination to risk receiving another.

The subject of giving up Kopfontein was often discussed, but even if it were done, it seemed evident that many months must elapse before Emson would be fit to travel; so the subject was talked of less often, though one thing was evident both to Dyke and his brother—their scheme of ostrich-farming had completely broken down, and unless a bold attempt were made to start afresh, they would gradually become poorer and poorer, for alone, all Dyke’s efforts to collect valuable skins were disposed to be rather unfruitful, try hard as he would.

Months had passed, and they had had no more black visitors, but one day Tanta Sal rushed into the house where the brothers were seated at dinner, with such a look of excitement upon her features, that Dyke sprang up, seized one of the guns and handed another to his brother, who stood up, looking weak, but determined to help if danger were at hand.

But Tanta gesticulated, pushed the guns away, and signed to Dyke to follow.

The cause of the woman’s excitement was evident directly, for there, a mile away, was a wagon drawn by a long team of oxen, and it was evident that they were to have visitors at the farm.

“Some poor wretch going up in the wilds to seek his fortune,” said Emson rather sadly. “I wish him better luck than ours, young un.”

“Oh, I say, Joe, don’t talk in that doleful way,” cried Dyke excitedly. “This is so jolly. It’s like being Robinson Crusoe and seeing a sail. Here, wait while I fetch the glass.”

Dyke returned the next minute with his hands trembling so that he could hardly focus and steady the “optic tube.” Then he shouted in his excitement, and handed the telescope to his brother.

“Why, it’s that fat old Dutchman, Morgenstern! Who’d have thought of seeing him?”

Sure enough it was the old trader, seated like the Great Mogul in the old woodcuts. He was upon the wagon-box, holding up an enormously long whip, and two black servants were with him—one at the head of the long team of twelve oxen, the other about the middle of the double line of six, as the heavy wagon came slowly along, the bullocks seeming to crawl.

“I am glad,” cried Dyke. “I say, Joe, see his great whip? He looked in the glass as if he were fishing.”

“Tant make fine big cake—kettle boil—biltong tea?” asked the Kaffir woman hospitably.

“Yes,” said Emson quietly. “But,” he continued, as Tanta Sal ran off to the back of the house, “it may not be Morgenstern, young un. Fat Germans look very much alike.”

“Oh, but I feel sure this is the old chap.—I say, what’s the German for fat old man?”

“I don’t know. My German has grown rusty out here. Dicker alte Mann, perhaps. Why?”

“Because I mean to call him that. He always called me booby.”

“No, bube:—boy,” said Emson, smiling.

They stood watching the wagon creeping nearer and nearer for a minute or two, Dyke longing to run to meet the visitors; but he suddenly recalled the orderly look at Morgenstern’s, and rushed back into the house to try to make their rough board a little more presentable; and he was still in the midst of this task, when, with a good deal of shouting from the Kaffir servants, and sundry loud cracks of the great whip, the wagon, creaking and groaning, stopped at the fence in front of the house, and the old German shouted:

“Ach! mein goot vrient Emzon, how you vas to-day? Vere is der bube?”

“Dicker alte Mann!” said Dyke between his teeth, and hurriedly brushing away some crumbs, and throwing a skin over the chest in which various odds and ends were kept, he listened to the big bluff voice outside as Morgenstern descended.

“It is goot to shack hant mit an Englander. Bood you look tin, mein vrient. You haf been down mit dem vever?”

“Yes, I’ve been very ill.”

“That is nod goot. Bood you ged besser now. Ach, here is der poy! Ach! mein goot liddle bube, ant how you vas?”

Dyke’s hands were seized, and to his horror the visitor hugged him to his broad chest, and kissed him loudly on each cheek.

“Oh, I’m quite well,” said Dyke rather ungraciously, as soon as he could get free.

“Ov goorse you vas. Grade, pig, oogly, shtrong poy. I am clad to zee you again. You did got home guite zave?”

“Eh? Oh yes. But that’s ever so long ago.”

“Zo? Ach! I haf been zo busy as neffer vas. Now you led mein two poys outspan, eh?”

“Of course,” said Emson warmly.—“Show them where the best pasture is, toward the water, Dyke.—Come in, Herr. You look hot and tired.”

“Ja, zo. I am sehr hot, and you give me zomeden to drink. I haf zom peaudivul dea in dem vagons. I give you zom to make.”

An hour later, with the visitor and his men refreshed, Morgenstern smiled at Dyke, and winked both his eyes. “You know vad I vants?” he said.

“Yes; your pipe.”

“Ja, I wand mein bibe. You gom mit me do god mein bibe und mein dobacco din; und den I light oop, und shmoke und dalk do you, und you go all round, und zhow me den ostridge-bird varm.”

They all went out together, the visitor noticing everything; and laying his hand upon Emson’s shoulder, he said: “You muss god besser, mein vrient. You are nod enough dick—doo tin.”

“Oh, I’m mending fast,” said Emson hastily, and then they stopped by the wagon, with Morgenstern’s eyes twinkling as he turned to Dyke.

“You haf been zo goot,” he said; “you make me ead und trinken zo mooch, dat I gannod shoomp indo den vagon. I am zo dick. Good! You shoomp in, and get me mein bibe und dobacco din.”

Dyke showed him that he could; fetched it out, and after the old man had filled, lit up, and begun to form smoke-clouds, he said: “You dake me now do see if mein pullocks and my poys is ead und trink.”

“Oh, they’re all right,” cried Dyke.

“Ja. Bood I always like do zee for meinzelf. Zom beobles ist nod as goot as you vas, mein vrient. A good draveller ist kind do his beast und his plack poy.”

The visitor was soon satisfied, for he was taken round to where Tanta Sal was smiling at her two guests, who, after making a tremendous meal, had lain down and gone to sleep, while the oxen could be seen at a distance contentedly grazing in a patch of rich grass.

“You haf no lions apout here,” said the old man, “to gom und shdeal mein gattle?—Ah, vot ist das?” he cried, turning pale as he heard a peculiar noise from somewhere close at hand. Quigg! “You ged der goon und shoot, or der lion gom und preak von of der oxen’s pack.”

“It’s all right,” cried Dyke, laughing. “Come and look here.”

The old man looked rather wild and strange, for, as Dyke threw open a rough door in the side of one of the sheds, the two lion cubs, now growing fast towards the size of a retriever dog, came bounding out.

“Ach! shdop. Do not led them ead der poor alter pecause he is zo nice und vat. Eh, dey will not hurt me?”

“No!” cried Dyke; “look here: they are as tame and playful as kittens.”

Dyke proved it by dropping on his knees and rolling the clumsy, heavy cubs over, letting them charge him and roll him over in turn.

“Ach! id is vonterful,” said the old man, wiping the perspiration from his face. “I did tought dey vas go to eat den alt man. You make dem dame like dot mit dem jambok.”

“With a whip? No,” cried Dyke; “with kindness. Look here: pat them and pull their ears. They never try to bite. You should see them play about with the dog.”

“Boor liddle vellows den,” said the old man, putting out his hand nervously. “Ach, no; id is doo bat, you liddle lion. Vot you mean py schmell me all over? I am nod for you do ead.”

Dyke laughed, for the cubs turned away and sneezed. They did not approve of the tobacco.

“There, come along,” he cried; and the cubs bounded to him. “I’ll shut them up for fear they should frighten your oxen.”

“Das is goot,” said the old man with a sigh of satisfaction, as he saw the door closed upon the two great playful cats. “Bood you zhall mind, or zom day I zhall gom ant zee you, but vind you are not ad home, vor die young lion haf grow pig und ead you all oop.”

“Yes,” said Emson; “we shall have to get rid of them before very long. They may grow dangerous some day.”

“Ach! I dell you vot, mein vrient Emzon, I puy dose lion ov you, or you led me shell dem, to go do Angland or do Sharmany.”

“Do you think you could?”

“Do I dink I good? Ja, I do drade in effery dings. I gom now to puy iffory und vedders. You shell me all you vedders, und I gif you good brice.”

“I have a very poor lot, Morgenstern, but I’ll sell them to you. Dyke and I have done very badly.”

“Zo? Bood you will zell do me. I zaid do myself I vould go und zee mein vrient Emzon und den bube. He zay I am honest man.—You droost me?”

“Of course,” said Emson frankly. “I know you for what you are, Morgenstern.”

The old man lowered his pipe, and held out his fat hand.

“I dank you, Herr Emzon,” he said, shaking his host’s hand warmly. “Id is goot do veel dot von has a vrient oud here in der desert land. Bood I am gonzern apout you, mein vrient. You haf peen very pad. You do look sehr krank; unt you zay you haf tone padly. I am moch gonzern.”

“We’ve been very unlucky,” said Emson, as the old man seated himself upon a block of granite, close to one of the ostrich-pens, while an old cock bird reached over and began inspecting his straw-hat.

“Zo I am zorry. Bood vy do you not dry somedings else? Hund vor skins or vor iffory? I puy dem all. Und not dry do keep den ostridge-bird in dem gage, bood go und zhoot him, und zell die vedders do me. Or der is anodder dings. Hi! You bube: did you dell den bruders apout den diamonts?”

“Oh yes, I told him,” said Dyke sadly; “but he has been so ill. I thought once he was going to die.”

“Zo! Den tunder! what vor you no gom und vetch me und mine old vomans? Die frau gom und vrighten avay das vevers. She is vonterful old vomans. She make you like to be ill.”

“I was all alone, and couldn’t leave him,” said Dyke. “I was afraid he would die if I did.”

“Ja, zo. You vas quite right, mein young vrient Van Dyke. You are a goot poy, unt I loaf you. Zhake mein hant.”

The process was gone through, Dyke shrinking a little for fear he would be kissed.

“Und zo die pirts do nod get on?” said Morgenstern after a pause, during which he sat smoking.

“No, in spite of all our care,” said Emson.

“Ach! vot ist das?” cried the old man, looking sharply round, as his hat was snatched off by the long-necked bird which had been inspecting it. “You vill gif dot pack to me, shdupit. Id ist nod goot do eat, und I am sure id vould not vid your shdupid liddle het.—Dank you, bube,” he continued, as Duke rescued and returned the hat. “Eh? you dink it goot. Vell, it vas a goot hat; bud you go avay und schvallow shdones, und make vedders for me to puy. Ach! dey are vonny pirts, Van Dyke. Und zo dey all go die?”

“We lost a great many through the Kaffir boy we had,” said Dyke, as they walked slowly back to the house.

“Zo? He did not give them do eat?”

“We saw that the birds had enough to eat,” said Dyke; “but he used to knock their heads with a stone.”

“Zo? Dot vas nod goot. Shdones are goot for die pirts to schvallow, bud nod for outside den het. I dink, mein younger vrient, I should haf knog dot shentleman’s het outside mit a shdone, und zay do him, ‘You go avay, und neffer gom here again, or I zhall bepper your black shkin mid small shot.’”

“That’s what Dyke did do,” said Emson, smiling.

“Zo? Ach! he is a vine poy.”

“Hah!” sighed the old man as he sank upon a stool in the house. “Now I zhall shmoke mein bibe, und den go do mein wagon und haf a big long schleep, vor I am dire.”

He refilled his pipe, and smoked in silence for a few minutes, and then said thoughtfully:

“Emzon, mein vrient, I am zorry to zee you veak und krank, und I am zorry do zee your varm, und I should not be a goot vrient if I did not dell you die truth.”

“Of course not,” said Emson; and Dyke listened.

“All dese has been a misdake. You dake goot advice, mein vrient. You led die long-legged pirts roon vere dey like, und you go ant look for diamonts.”

Emson shook his head.

“No,” he said, “I am no diamond hunter. It would not be fair for my brother, either. I have made up my mind what to do. I am weak and ill, and I shall clear off and go back home.”

“Nein, nein. Dot is pecause you are krank. Bube, you make your bruder quite vell und dry again. Dot is der vay. You shall nod go home to your alt beobles und say, ‘Ve are gom pack like die pad shillings. No goot ad all.’”

“That’s what I say,” cried Dyke eagerly. “I want to hunt for diamonds, and collect feathers, and skins, and ivory.”

“Goot! Und gom und shell all to alt Oom Morgenstern.”

“Yes,” cried Dyke. “I say: help me to make my brother think as I do.”

“Of goorse I will, bube; I know,” said the old man, winking his eyes. “It ist pecause he has got das vevers in his pones; bud I haf in mein wagon zix boddles of vizzick to vrighten avay all dot. I zhall give him all die boddles, und I shall bud indo each zom quinines. Id ist pord wein, und he vill dake two glass, effery day, und fery zoon he vill laugh ad dem vevers und zay: ‘Hi! Van Dyke, get on your horse and go mit me to get iffory, und vedders, und skins, und diamonts, till we haf got a load, und den we vill go und shell dem to alt Oom Morgenstern—do dem alt ooncle, as you gall him.’—Vot haf you got dere, bube?”

“Two or three of the ostrich skulls that I found with the marks made in them by the Kaffir with a stone,” said Dyke, who had just been and opened the door of his case of curiosities.

“Zo!” said the old man. “Ah, und negs time you see dot Kaffir poy you make zome blace like dot upon der dop of his het. Und vot else have you there?—any dings to zell me?”

“Oh no; only a few curiosities I picked up. Look! I took these all out of the gizzard of an old cock ostrich we were obliged to kill, because he broke his leg.”

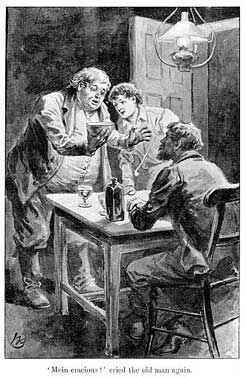

Dyke handed a rough little wooden bowl to the old man.

“Ach! Mein cracious!” he cried.

“You wouldn’t have thought it. And here’s a great piece of rusty iron that he had swallowed too; I picked it out when I had lost a knife, and thought he had swallowed it.”

“Mein cracious!” cried the old man again, and he let his pipe fall and break on the rough table.

Dyke laughed as the visitor turned over the stones and the bit of rusty iron.

“One would have thought it would kill them to swallow things like that, but they’re rare birds, Herr Morgenstern; they’ll try and swallow anything, even straw-hats.”

“Mein cracious, yes!” cried the old man again. “Und so, bube, you did vind all dose—dose dings in dem gizzard ov dot pirt?”

“Yes, all of them. I’ve got another bowlful that I picked up myself. There are a good many about here.”

“You vill let me loog ad dem, mein younger vrient?”

“Of course,” said Dyke, and he fetched from the case another rough little bowl that he had obtained from one of the Kaffirs.

There were about ten times as many of the stones, and with them pieces of quartz, shining with metallic traces, and some curious seeds.

Morgenstern turned them over again and again, and glanced at Emson, who looked low-spirited and dejected.

“Ach, zo! Mein cracious!” cried the old man; then, with his voice trembling: “Und zo there are blendy of dose shdones apout here?”

“Yes; I’ve often seen the ostriches pick them up and swallow them. I suppose it’s because they are bright.”

“Yes, I suppose it ist pecause they are zo bright,” said the old man, pouring out a handful of the stones into his hand, and reverently pouring them back into the rough wooden bowl. Then rising, he shook hands silently with Dyke.

“Going to bed?”

“No, mein younger vrient, nod yed. I haf somedings to zay to your bruder,” and turning to Emson, who rose to say good-night to him, he took both his hands in his own, and pumped them up and down.

“Yoseph Emzon,” he said, in a deeply moved voice, “I like you when you virst game into dese barts, und I zay dot man is a shentleman; I loaf him, unt den bube, his bruder. Now I gom here und vind you ill, my heart ist zore. I remember, doo, you zay I vas honest man, ant I dank den Lord I am, und dot I feel dot I am, und can say do you, mein young vrient, zom beobles who know what I know now would sheat und rob you, but I vould not. I vont zom days to die, und go ver der Lord vill say, ‘Vell done, goot und vaithful zervant.’ Yoseph Emzon, I am honest man, und I zay do you, all your droubles are over. You haf been zick, but you vill zoon be quide vell und shdrong, vor you vill not haf das sore heart, und de droubles which make do hair drop out of your het.”

“Thank you, Morgenstern. I hope I shall soon be well enough to go,” said Emson, sadly.

“Bood you vill not go, mein vrient,” cried the old man. “You vill not leave here—mein cracious, no! You vill shdop und get all die ostridge you gan, und shend dem out effery day to big oop zom shdones, und den you vill dig oop der earth vor die pirts to vind more shdones, und when dey haf shvallowed all dey gan, you und der bube here vill kill dem, und empty die gizzards into die powls of water to vash dem.”

“No, no, no: what nonsense!” cried Emson, while Dyke suddenly dashed to the table, seized one bowl, looked at its contents, and banged them down again.

“Hurray!” he yelled. “Oh! Herr Morgenstern, is it real?” For like a light shot from one of the crystals, he saw the truth.

“Nonsense, Yoseph Emzon?” cried the old man. “Id is drue wisdom, as goot as der great Zolomon’s. Yoseph Emzon, I gongradulade you. You haf had a hart shdruggle, but it is ofer now. Die ostridge pirts haf made you a ferry rich man, und I know dot it is right, for you vill always do goot.”

“But—but—do I understand? Are those—those—”

“Yes, Joe,” roared Dyke, springing at his brother. “There is no more room for despair now, old chap, for you are rich; and to think we never thought of it being so when you were so unhappy, and—and—Oh, I can’t speak now. I don’t care for them—only for the good they’ll do to you, for they’re diamonds, Joe, and there’s plenty more diamonds, and all your own.”

“Yes, und pig vons, too,” said the old trader, with a look of triumph; “und now I must haf somedings to trink. I haf dalk so much, I veel as I shall shoke. Here, bube, you go und shoomp indo dem vagon, und bring one of die plack poddles out of mein box py vere I shleep. Id is der bruder’s vizzick, bud ve vill trink a trop to-night do gongradulade him, und you dwo shall trink do der health of dis honesd alt manns.”

The bottle of port was fetched, a portion carefully medicated with quinine, and Morgenstern handed it to the invalid.

“Mein vrient,” he said, “das is wein dot maketh glad das heart of man. I trink do your goot health.”

A few minutes later the old trader said softly:

“I go now to say mein brayer und get mein schleep. Goot-night, mein vrients, und Gott pless you both.”

It was about an hour later, when the faint yelping of the jackals was heard in the distance, that Emson said softly:

“Asleep, young un?”

“No, Joe; I can’t get off nohow. I say, am I dreaming, or is all this true?”

“It is true, lad, quite true; and I suppose that you and I are going to be rich men.”

“Rich man and boy, Joe. I say: are you pleased?”

“More thankful than pleased, Dyke, for now, when we like, we can start for home.”

“Without feeling shamefaced and beaten, eh, Joe? Then I am glad. I didn’t quite know before, but I do know now; and we can make the old people at home happy, too, Joe.”

“As far as money can make them so, little un.”

“Hullo!” cried Dyke; “you are a bit happy after all, Joe.”

“What makes you say that?”

“You called me ‘little un’ just in your old way, and I can feel that, with all the worry and disappointment gone now, you’ll be able to get well.”

Emson was silent for a few minutes, and then he said softly:

“Yes: I feel as if I can get better now; not that I care for the riches for riches’ sake, Dyke, but because— Are you listening, little un?”

Dyke was fast asleep, and a few minutes later Emson was sleeping too, and dreaming of faces at home in the old country welcoming him back, not for the sake of the wealth he brought, but because he was once more a hale, strong man.