Chapter 5 | Pretty Pussy | Featherland

A nice job had Mr and Mrs Spottleover with their young ones; they were not amiable and dutiful children, but spent all their time in grumbling and shouting for more food, till they nearly drove the old folks mad, and Mrs Spottleover said she would never have been married if she had known; “no; that she wouldn’t.” Tiresome children hers were, for they were no sooner hatched, and lay at the bottom of the nest all eyes and mouth, with just a patch of grey woolly fluff stuck on their backs, than they began to open their great beaks, and gorge everything the old ones brought; till you would almost have thought they must have killed themselves; but they did not; they only grew; and that, too, at such a rate, that before they were fledged they used to push, crowd, and fight because, they said, the nest was too tight; and it was almost a wonder nobody fell overboard. Beautiful beaks they had, too, as they grew older, and sweet voices, that subsided into a querulous grumbling when the old birds had gone; but directly father or mother returned, tired and panting, to settle on the bush, up popped every bird, and strained every neck, and wide open sprang every beak, ready for the coming “slug, grub, or wire-worm.”

“My turn—my turn—my turn—my turn,” chorused the voices; ready to snap up the coming morsel like insatiable young monsters as they were; and this time it was a fine fat worm that Mrs Spottleover found on the grass plot far away from his hole, and had killed and then brought him in triumph to her little ones for breakfast.

“Now, one at a time, children; one at a time; don’t be greedy,” said dame Spottleover; and then she popped the beautiful, juicy, macaroni-like morsel into the beak of number one, who began to gobble it down for fear anyone else should get a taste; but number four saw a chance, and snapped hold of the other end of the worm and swallowed ever so much, till at last he and his brother had their heads close together; when they began to pull and quarrel—quarrel and pull—till Mrs Spottleover turned her own beak into a pair of scissors, snipped the disputed morsel in two, boxed both the offenders’ ears, said she would take the worm away—but did not, as it was all gone—and then flew off for a fresh supply.

In came father with three green caterpillars fresh from off the cauliflowers, popped them in as many beaks, and he, too, flew off on his day’s work to hunt out savoury morsels for his little tyrant-like children.

“I can fly,” said number three; “I know I can. I mean to try soon, and get my own bits. I know I can.”

“You can’t,” said one brother; “you can’t. You would come down wop! and couldn’t get up again. You ain’t strong enough to fly yet.”

“I am. I could fly ever so high; and I’d show you, if I liked, but I don’t like.”

“Ah! you’re afraid.”

“No; I’m not.”

“Yes; you are.”

“No; I’m not. There’s a wing now,” said the fledgeling, spreading out his half-penned pinion. “Couldn’t I fly with that?”

“Oh!” roared the other disputant, “that’s right in my eye. Oh, dear; oh, dear; won’t I tell when mother comes back.”

“Tchut, tchut, children,” said the dame, flying to the nest; “quiet, quiet, there’s the green-eyed tiger that killed your grandfather coming; so thank your stars that you are safe in the nest your father and I made for you; for yon wretch would, if it could, make mouthfuls of you all.”

But Mrs Pussy with her striped sides, and long, lithe sweeping tail, did not know of the thrushes’ nest, and so went quietly and softly down the path towards the hollow cedar-tree. Here and there lay a wet leaf or two; and when quiet Mrs Puss put her velvet paw on one it would stick to it, and set her twitching and shaking her leg till the leaf was got rid of, when she licked the place a little and went on again. Ah! so soft and smooth and velvety was Mrs Puss, looking as innocent as the youngest of kittens, and without a thought of harm to anybody. Walking along so softly, and not noticing anything with one eye, but keeping the other slyly fixed upon friend Specklems, who was high up on a dead branch, making believe to sing to his good lady, who was two feet deep in a hole of the cedar, sitting upon four beautiful blue eggs. And beautifully Specklems, no doubt, thought he sang, only to a listener it sounded to be all sputter and wheezle—chatter and whistle; but he kept on. All the while puss crept gently up to the trunk of the tree, only just to rub herself up against it, backwards and forwards; nothing more. But, somehow, Mrs Puss was soon up the trunk, and close to the nest-hole before the starling saw her; but he did at last, with her paw right down in the hole. “Now, thief,” he shouted, perking himself up and looking very fierce; but all the while trembling lest puss should draw out his wife tangled up in the nesting stuff. “Now, come, out of that.”

Mrs Puss gave a slight start, and peering up saw Specklems looking as fierce about the head as an onion stuck full of needles; but she did not draw forth her paw until she had, by carefully stretching it out as far as possible, found that she could not reach the nest.

“Dear me, how you startled me, Mr Specklems,” she said; “who ever would have thought of seeing you there?” and then she began sneaking and sidling up towards the bird, of course with the most innocent of intentions; and though not in the slightest degree trusting Mrs Puss, Specklems sat watching to see what she would do next.

“It’s a nice morning, isn’t it?” she continued mildly, but at the same time drawing her wicked-looking red tongue over her thin lips as though she thought Specklems would be nicer than the morning. “It’s a nice morning, isn’t it? and how Do you do, my dear sir? You see I am taking a ramble for my health. I find that I want fresh air; the heat of the kitchen fire quite upsets me sometimes, and then I come out for a stroll, and get up the trees just to hear the sweet warbling of the songsters.”

“Humph!” said Specklems to himself, “that’s meant for a compliment to my singing; but I know she’s after no good.”

“The kitchen was very, very hot this morning,” continued Puss, “and so I came out.” And this was quite true, for the kitchen was hot that morning—too hot to hold Mrs Puss, for cook had run after her with the fire-shovel for licking all the impression off one of the pats of butter, just ready for the breakfast parlour, and leaving the marks of her rough tongue all over the yellow dab, and hairs out of her whiskers in the plate; and then when cook called her a thief, she stood licking her lips at the other end of the kitchen, and looking so innocent, that cook grew quite cross, caught up the shovel, and chased puss round the kitchen, till at last the cat jumped up on cook’s shoulder, scratched off her cap, and leaped up to the open skylight and got away; while poor cook was so frightened that she fell down upon the sandy floor in a fainting fit, but knocked the milk-jug over upon the table as she went down, which served to revive her, for the milk ran in a little rivulet right into one of the poor woman’s ears, filled it at once like a little lake, and then flowed down her neck, underneath her gown, and completely soaked her clean white muslin handkerchief. And so Mrs Puss found the kitchen very hot that morning, and took a walk in the garden.

“Let me hear you sing again, sir,” said Puss, creeping nearer and nearer. “That piece of yours, where you whistle first, and then make that sweet repetition, which sounds like somebody saying ‘stutter’ a great many times over very quickly. Now, do, now; you folks that can sing always want so much pressing.”

Poor Specklems! he hardly knew what to do at first; but he had wit enough to be upon his guard while he sang two or three staves of his song.

By this time Puss had managed to creep within springing distance of poor Specklems; and just in the midst of one of her smooth oily speeches she made a jump, open-mouthed and clawed, but missed her mark, for the starling gave one flip with his wing and was out of reach in an instant, and then, with a short skim, he alighted on the thin branch of a neighbouring tree, where he sat watching his treacherous enemy, who had fared very differently. Crash went Mrs Puss right through the prickly branches of the cedar, and came down with her back across the handle of the birch-broom, which still stuck in the tree, and made her give such an awful yowl, that the birds all came flocking up in time to see Mrs Puss go spattering down the rest of the distance, and then, as a matter of course, she fell upon her feet, and walked painfully away, followed by the jeers of all the birds, who heard the cause of her fall, while she went off spitting and swearing in a most dreadful manner, and looking as though her tail had been turned into a bottle-brush, just at the time her coat was so rough that it would be useful to smooth it.

Poor Mrs Puss, she nearly broke her back, and she went off to the top of the tool-shed, where the sun shone warmly, and there she set to and licked herself all over, till her glossy coat was smooth again, when she curled herself up in a ball and went fast asleep, very much to the discomfort of a pair of redstarts, who were busy building their nest under the very tile Mrs Puss had chosen for her throne.

“A nasty, deceitful, old, furry, green-eyed, no-winged, ground-crawling monster,” said Mrs Specklems. “There I sat, with its nasty fish-hook foot within two or three inches of my nose, and there it was opening and shutting, and clawing about in such a way, that I turned all cold and shivery all over, and I’m sure I’ve given quite a chill to the eggs; and dear, dear, what a time they are hatching! Don’t you think that if we were both to sit upon them they would be done in half the time? Here have I been sit-sit-sit for nearly twenty days down in that dark hole; and if we are to have any more such frights as that just now, why, I do declare that I will forsake the nest. The nasty spiteful thing, it ought to be pecked to death.”

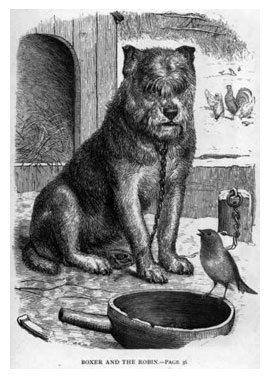

But Mrs Puss was not to go unpunished for her wrongful dealings; about half an hour after she had been asleep, who should come snuffing about in the garden but Boxer, the gardener’s ugly, old rough terrier. He had no business at all in the garden, but had managed to get his chain out of the staple, and there he was running about, and dragging it all over the flower beds, and doing no end of mischief; then he made a charge at Mrs Spottleover, who was on the lawn, where she had just punched out a fine grub, but she was so frightened at Boxer’s rough head and hair-smothered eyes, that she dropped her grub and went off in a hurry. Over and over went Boxer in the grass, having such a roll, and panting and lolling out his great red tongue with excitement, and then working away with both paws at his collar till he got it over his little cock-up ears, and then he gave his freed head such a shake that the ears rattled again. Then away he went, sniffing here, snuffing there, jumping and snapping at the birds far above, and coming down upon the ground with all four legs at once, and racing about and playing such strange antics, capers, and pranks, that the birds all laughed at the stupid, good-natured-looking dog, and did not feel a bit afraid of him.

All at once Boxer gave a sharp sniff under the cedar-tree, just where Mrs Puss had tumbled down, and then sticking his ears forward, his nose down, and his tail straight up, he trotted off along the track Mrs Puss had made, until he came close to the tool-shed, where, looking up, he could just see a part of Pussy’s shining fur coat leaning over the tiles. Now, Boxer was a very sly old gentleman, and when he saw the birds flocking after him to see what he would do, he made them a sign to be quiet, and put his paw up to the side of his wet black nose, as much as to say, “I know;” and then he trotted off to the melon frames, walked up the smooth sloping glass till he could jump on to the ivy-covered wall, where he nearly put his foot in the hedge-sparrow’s nest, and so on along the top till he came to the tool-shed, where his enemy, Mrs Puss, lay curled up, fast asleep.

They were dreadful enemies were Mrs Puss and Boxer, for the cat used to go into the yard where the dog was chained up, and, after spitting and swearing at him, on more than one occasion took advantage of his being at the end of his chain, and keeping just out of his reach scratched the side of his nose, and tore the skin so that poor Boxer ran into his kennel howling with pain, rage, and vexation; while Mrs Puss, setting her fur all up, marched out of the yard a grander body than ever. And then, too, she used to get all the titbits out of the kitchen that would have fallen to Boxer’s share; and he, poor fellow, used often to say to the robin-redbreast who came for a crumb or two, that the pieces he sometimes had smelt catty, from Puss turning them over and then refusing them, when they came to the share of the poor dog.

So Boxer never forgave the scratch on his nose, nor yet Mrs Puss’s boast that he was afraid of her; so he walked softly along the wall, and on to the tool-shed, and with one bouncing leap came down plop upon the treacherous old grimalkin.

“Worry-worry-worry-ur–r–r–ry,” said Boxer, as he got hold of Pussy’s thick skin at the nape of her neck, and shook away at it as hard as he could.

“Wow-wow-wiau-au-au-aw,” yelled Puss, wakened out of her sleep, and in vain trying to escape.

“Hooray!” said the birds, flying round and round in a state of the greatest excitement.

“Give it her, Boxer,” shouted Mr Specklems, remembering the morning’s treachery.

And then off they rolled on to the ground, and over and over, righting, howling, and yelling, till Mrs Puss made a desperate rush through a gooseberry bush, and a thorn went so sharply into Boxer’s nose that he left go, and away went Puss across the garden till she came to the wall, and was scrambling up it, when Boxer had her by the tail and dragged her down again. But Puss made another rush towards the gate, dragging Boxer after her, till she came to the trellis-work opening, through which she dragged herself, and a moment after Boxer stood looking very foolish, with a handful of fur off Puss’s tail in his mouth; while she, with her ragged ornament, was glad enough to sneak in-doors frightened to death, and get to the bottom of the cellar, where she scared cook almost into fits, by sitting upon a great lump of coal, with her eyes glaring like a couple of green stars in the dark.

“Wow-wow-wow—bow-wow-wuff,” said Boxer at last, when he found that his enemy had gone. “Wuff-wuff,” he said again, trying to get rid of the fur sticking about his mouth. “Wuff-wuff,” he said, “that’s better.”

“Bravo!” chorused the birds, in a state of high delight; “well done, Boxer!”

“Ha-ha-ha; phut-phut-phut—wizzle-wizzle,” said the starling off the top of the wall.

“Wizzle-wizzle, indeed,” said Boxer grumpily; “why don’t you come down, old sharp-bill, and pull this thorn out of my nose?”

“’Tisn’t safe,” said the starling.

“Get out,” said Boxer; “why, what do you mean?”

“You’d get hold of my tail, perhaps,” said Specklems.

“Ha-ha-ha,” laughed all the birds; “that’s capital, so he would.”

“No, no; honour bright,” said Boxer. “You never knew me cheat; ask Robin, there.”

Whereupon the robin came forward in a new red waistcoat, blew his nose very loudly, and then said:—

“Gentlemen all, I could, would, should, and always have trusted my person freely with my friend—if he will allow me to call him so,”—here the robin grew quite pathetic, and said that often and often he had been indebted to his friend for a sumptuous repast, or for a draught of water when all around was ice; he assured them they might put the greatest trust in Boxer’s honour.

Whereupon Boxer laid himself in the path, and the birds dropped down one at a time, some on the beds, some on the gooseberry or currant bushes, and formed quite a cluster round the great, rough, hairy fellow, for they felt perfectly safe after what the robin had said.

First of all, the starling examined the wound with great care, and said, “The thorn is sticking in it.”

“Well, I knew that,” said Boxer; “pull it out.”

He spoke so sharply that every one jumped, and appeared as if about to fly off; but as the dog lay quite still, Specklems laid hold of the thorn, and gave a tug at it that made Boxer whine; but he did not get it out, so tried again.

“Some one come and lend a hand here,” said the starling; and then two or three birds, one after another, joined wings and pulled away with a hearty “Yo, ho,” until all at once out came the thorn, and down fell the haulers all in a heap upon the ground, where they fluttered and scrambled about, for their legs and wings had got so mixed up together that there was no telling which was which; and the only wonder was that the thrush did not come out of the scramble with the starling’s wings, and the blackbird with somebody else’s tail. However, at last they were all right again, and Boxer declared he was so deeply indebted to the birds that he must ask them all to his kennel in the yard to help him to eat his dinner next day.

Then the birds whistled and chattered, piped and sang; Boxer gave two or three barks and jumps off the ground to show his satisfaction, although his nose was bleeding; while all the time Mrs Puss sat alone in the coal-cellar, making use of most dreadful cat-language, and determining to serve the birds out for it some day.

When a proper amount of respect had been shown upon both sides, the birds flew off to their green homes, to attend to the wants of their young ones, and to finish nesting; while Boxer went back to his green kennel and made himself a nest amongst his clean straw.