Chapter 9 | A Tall Gentleman | Featherland

“Hum!” said Mrs Spottleover one morning to Mrs Flutethroat, after they had been having a wash in the bright pure water. “Hum!” she said, looking at the duck’s brood of little downies swimming about after her, and one of them with a bit of shell sticking to its back. “Hum! yes, pretty well, but why yellow?”

“Ah! my dear, they will come white; they’re not bleached yet. But they are strong, aren’t they? Look at the little ones, now, only four hours old, and feeding themselves! Don’t you wish yours would? Only think of the trouble they give before they can feed alone!”

“Well!” said Mrs Spottleover, “that’s all very well, but, after all, those little downy balls take as much looking after as our little ones; and then only think of one’s child growing up to say nothing better than ‘Quack-quack,’ besides being flat-nosed and frog-footed. Depend upon it, my dear, things are best as they are!”

“Well, I suppose you are right,” said Mrs Flutethroat; “but I must not stay here gossiping, for I have no end of work to do this morning.” Saying which the hen blackbird shook out her long dusky wings, cried “Pink-pink-pink,” and flew off to the laurel bush to attend to her little ones; while the thrush hopped up into a tree to see how the haws were getting on, and whether there would be a good crop for the winter.

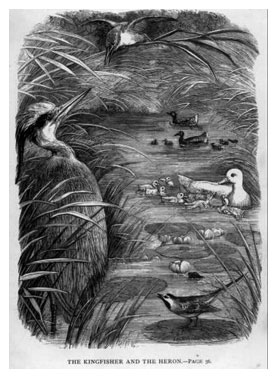

Just then there was a great shadow passed over the pond, and the ducklings splashed through the water, because they were so frightened, and then flop-flop, flip-flop, flip-flop, there came old Shadowbody, the heron, to the pond, and pitched down by the haunt of the kingfisher, where he stood with his long stilty legs half in the water, his great floppy wings doubled up close to his sides, and his long neck squeezed between his shoulders all of a bundle; and there he stood looking as though he were going to sleep; but not a bit of it, old Shadowbody, or Bluescrags, as some of the saucy young birds called him, did not stand by the side of a pond to go to sleep, but to look after his dinner.

By-and-by the ducklings, seeing that the heron did not move, came nearer to him; and at last a little white fly went sailing along under his beak, and two ducklings set off on a race over the surface of the pond to see which would get the little white fly; and so busy were they that they forgot all about the great heron, and went up close to him, splashing him all over with the bright sparkling water.

“Take that, you ugly little downy dab,” said the heron in a pet. “Do you think I came here to be made a water-mop of? Get out with you! see how you’ve wetted my waistcoat. Take that!”

And the poor little duckling did take that, and scampered off to its mother, crying out in such a pitiful voice, “Wheedle-wheedle-wheedle,” that the heron forgot his ill-humour and burst out laughing, and felt quite sorry that he had given poor little Yellow-down such a cruel poke in its back with his long sharp beak.

“Serve it right, though,” said the heron; “coming splashing, and dashing, and sending the water all over a sedate, quiet gentleman, quietly fishing by the side of a pond! And a nice pond it seems too, with plenty of fish in it. It strikes me I shall often come here.”

Just then Bluescrags made a poke at a fish, and caught it in his long bill, and gobbled it up in no time. But he was not to enjoy himself long, for the duck was telling all her neighbours about the ill-usage her little one had received; and the mischief-making little wagtail thought as he had seen the lanky bird eating what he called the kingfisher’s fishes, he would go and tell, and then sit on the bank and see the quarrel there would be; for he considered that the heron had no more business to take the fish out of the pond than the toad had to catch flies. So he ran to the blue bird’s hole, and sticking in his little thin body, he ran up it to the nest, shouting, “Neighbour, neighbour; thieves, thieves!”

“Where, where?” said Ogrebones the kingfisher.

“Here; running away with your fish by the dozen,” said the wagtail.

“Well, get out of the way,” said the kingfisher, bustling out of the nest and going towards the mouth of the hole. “There, do make haste.”

But the wagtail couldn’t make haste, for his tail was so long he could not turn round in the hole, and so had to walk backwards the best way he could, with the points of his tail-feathers catching against the wall and sending him forwards upon his beak, and making the old kingfisher so crabby, that at last he gave the poor wagtail a dig with his heavy beak that made him cry out, “Peek-peek-peek.”

“Then why don’t you get out of the way, when all one’s fish are being taken and stolen?”

Now the wagtail thought this very strange behaviour, when he had taken the trouble to let old Ogrebones know, and so he very wisely made up his mind never to interfere with other people’s business again; for, said he, as he got out of the hole at last, “I don’t know but what the heron has as good a right to the fish as old surly has; at all events, I’ll never fetch him out any more.”

Out bounced the kingfisher—“Here! hi! I say! you, there! what are you after, impudence? Do you know that you are poaching?”

“Eh?” said the heron, looking at the showy little bird that was flitting round him with his feathers sticking up, and looking as though he were in a terrible passion; “Eh?” said the heron, “what’s poaching?”

“What’s poaching, ignoramus? why, taking other people’s fish. Don’t you know who I am?” said the kingfisher, sitting upon a spray and looking very self-satisfied and important.

“No,” said the heron; “I don’t know you. But you are not a bad-looking little fellow; only you are small—very small. Why, where are your legs?”

“Come, now,” said Ogrebones, “none of your impudence, old longshanks. I’m the king—the kingfisher; and I order you off; so go at once.”

“Ho-ho-ho,” laughed the tall bird. “And pray who made you a king? I’m not going to be driven off by such a scrubby little thing as you, even if you have got such grand feathers on your back. Why, if I were to shut my bill upon your neck, that head of yours would drop off regularly scissored, and then you’d be just such a king as Charles the First.”

“Oh, dear!” said the kingfisher, “only hark at him! I never heard such a character before in my life.”

“He nearly killed one of my little ones,” quacked the duck, coming up.

“Stuck his beak in my back,” said a frog, putting his nose out of the water; and then seeing that the heron was going to make a dart at him, “Ouf,” said he, popping down again in a hurry, and never stopping until had crept close down to the bottom of the pond where he crept under the weeds, and lay there all day, lost frightened to death.

“Keep your little flat bills at home, ma’am,” said the heron. “But really,” he said politely, “I did not know they were yours, or I should not have done so; but who would have thought that those little yellow dabs were children of such a beautifully white and graceful creature as you are?”

Whereupon the duck blushed, and spread one of her webbed feet before her face, and looked quite pleased at the compliment.

“Don’t listen to him,” croaked the kingfisher, backing into his hole; “he’s a cheat, and a bad character, and thief, and a—”

But the heron here made a poke at his royal highness with his great scissors bill, and the kingfisher scuffled out of sight in a fright, having learnt the lesson that a small tyrant, however grandly he may dress, is not always believed in; for with all his bright colours and gaudy plumes he was no match for the great sober-hued, flap-winged heron, who only laughed at him, and all his grand swaggering; and, as soon as he was gone, settled himself down to his work, and caught fish enough for a good meal, for he felt quite certain that he had as good a right to the fish as the little king, who had had it his own way so long that he thought everybody would give way to him.

Poke went the heron’s bill, and out came a finny struggler; but it was no use to kick, for Bluescrags never left go when once he had hold of a fish, and he was just gobbling it down when—

“Hillo-ho-ho-o-o,” cried a voice, and looking towards the place from whence the sound proceeded, the heron, as he rose from the ground, saw a man holding upon his hand a large sharp-winged bird, with a cruel-looking mouth, like that belonging to Hookbeak, the hawk, who sometimes passed over the garden, and such bright yellow and black piercing eyes, that as soon as Bluescrags felt their glance meet his, he turned all of a shiver, and his feathers began to ruffle up as though he were wet. But there was no time to shiver or shake, for the great bird was coming after him at a terrible rate, every beat of his pointed wings sending him dashing through the air, and in another moment the strange, fierce bird would have had the sharp claws he stretched out in the poor heron, but for the sudden and frantic effort he made to escape.

All this while Mrs Flutethroat was crying, “Pink-pink-pink” in the shrubbery, in a state of the greatest alarm, for a man had passed by the place where she was teaching her young ones to fly, carrying a bird on his gloved hand; while the bird had a curious cap upon its head, so contrived that it could not see anything; but the blackbird could see its yellow legs and cruel hooked claws that were stuck tightly into the thick glove the man wore.

“Well,” said Mrs Flutethroat, “I’m very glad he’s a prisoner, for the nasty, great, cruel-looking thing must be ten times worse than Hookbeak, the hawk, and if it were let loose here we should all be killed. Pink-tchink-chink,” she cried in alarm; for just then the man, who was a falconer, took his bird’s hood off, and shouted at the heron by the pond. The great flap-winged bird immediately took flight, and then, with a dash of its wings, away went the falcon, leaving Mrs Flutethroat shivering with fear.

Flip-flap, flap-flip-flop went the heron’s wings over the water; flip and skim went the falcon’s, and then away and away over the woods and fields went the two birds, circling round and round, and higher and higher; the falcon trying to get above the heron, so as to dart down upon him and break his wings; and the heron, knowing that as long as he kept up the falcon could not touch him, trying his best to keep the higher. At last the swift-winged bird darted upwards, and hovering for a moment over the poor heron, who cried out with fear, darted down with a rush, and went so close that he rustled through the quill feathers of the heron; and so swift was the dart he made, that he went down—down far enough before he could stop himself, and then when he looked up again, he saw that the heron had risen so high that there was no chance of catching him again; so off he flew, and perched in the cedar-tree at Greenlawn, where he sat cleaning and pruning his feathers, and sharpening his ugly hooked beak till it had such a point that it would have been a sad day for the poor bird who came in his clutches; while his master, who had lost sight of him, was wandering away far enough off, whistling to him to come back to his perch.