Chapter 16 | Prisoners Again | The Adventures of Don Lavington

Don’s grasp tightened on the rope, and as he lay there, half on, half off the slope, listening, with the beads of perspiration gathering on his forehead, he heard from below shouts, the trampling of feet and struggling.

“They’ve attacked Jem,” he thought. “What shall I do? Go to his help?”

Before he could come to a decision the noise ceased and all was perfectly still.

Don hung there thinking.

What should he do—slide down and try to escape, or climb back?

Jem was evidently retaken, and to escape would be cowardly, he thought; and in this spirit he began to draw himself slowly back till, after a great deal of exertion, he had contrived to get his legs beyond the eaves, and there he rested, hesitating once more.

Just then he heard voices below, and holding on by one hand, he rapidly drew up a few yards of the rope, making his leg take the place of another hand.

There was a good deal of talking, and he caught the word “rope,” but that was all. So he continued his toilsome ascent till he was able to grasp the edge of the skylight opening, up to which he dragged himself, and sat listening, astride, as he had been before the attempt was made.

All was so still that he was tempted to slide down and escape for no sound suggested that any one was on the watch. But Jem! Poor Jem! It was like leaving him in the lurch.

Still, he thought, if he did get away, he might give the alarm, and find help to save Jem from being taken away.

“And if they came up and found me gone,” he muttered, “they would take Jem off aboard ship directly, and it would be labour in vain.”

“Oh! Let go!”

The words escaped him involuntarily, for whilst he was pondering, some one had crept into the great loft floor, made a leap, and caught him by the leg, and, in spite of all his efforts to free himself, the man hung on till, unable to kick free, Don was literally dragged in and fell, after clinging for a moment to the cross-beam, heavily upon the floor.

“I’ve got him!” cried a hoarse voice, which he recognised. “Look sharp with the light.”

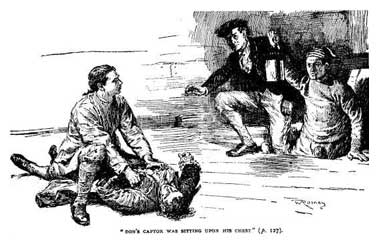

Don was on his back half stunned and hurt, and his captor, the sinister-looking man, was sitting upon his chest, half suffocating him, and evidently taking no little pleasure in inflicting pain.

Footsteps were hurriedly ascending; then there was the glow of a lanthorn, and directly after the bluff-looking man appeared, followed by a couple of sailors, one of whom bore the light. “Got him?”

“Ay, ay! I’ve got him, sir.”

“That’s right! But do you want to break the poor boy’s ribs? Get off!”

Don’s friend, the sinister-looking man, rose grumblingly from his captive’s chest, and the bluff man laughed.

“Pretty well done, my lad,” he said. “I might have known you two weren’t so quiet for nothing. There, cast off that rope, and bring him down.”

The sinister man gripped Don’s arm savagely, causing him intense pain, but the lad uttered no cry, and suffered himself to be led down in silence to floor after floor, till they were once more in the basement.

“Might have broken your neck, you foolish boy,” said the bluff man, as a rough door was opened. “You can stop here for a bit. Don’t try any more games.”

He gave Don a friendly push, and the boy stepped forward once more into a dark cellar, where he remained despairing and motionless as the door was banged behind him, and locked; and then, as the steps died away, he heard a groan.

“Any one there?” said a faint voice, followed by the muttered words,—“Poor Mas’ Don. What will my Sally do? What will she do?”

“Jem, I’m here,” said Don huskily; and there was a rustling sound in the far part of the dark place.

“Oh! You there, Mas’ Don? I thought you’d got away.”

“How could I get away when they had caught you?” said Don, reproachfully.

“Slid down and run. There was no one there to stop you. Why, I says to myself when they pounced on me, if I gives ’em all their work to do, they’ll be so busy that they won’t see Mas’ Don, and he’ll be able to get right away. Why didn’t you slither and go?”

“Because I should have been leaving you in the lurch, Jem; and I didn’t want to do that.”

“Well, I—well, of all—there!—why, Mas’ Don, did you feel that way?”

“Of course I did.”

“And you wouldn’t get away because I couldn’t?”

“That’s what I thought, Jem.”

“Well, of all the things I ever heared! Now I wonder whether I should have done like that if you and me had been twisted round; I mean, if you had gone down first and been caught.”

“Of course you would, Jem.”

“Well, that’s what I don’t know, Mas’ Don. I’m afraid I should have waited till they’d got off with you, and slipped down and run off.”

“I don’t think you’d have left me, Jem.”

“I dunno, my lad. I should have said to myself, I can bring them as ’ud help get Mas’ Don out; and gone.”

Don thought of his own feelings, and remained silent.

“I say, Mas’ Don, though, it’s a bad job being caught; but the rope was made strong enough, warn’t it?”

“Yes, but it was labour in vain.”

“Well, p’r’aps it was, sir; but I’m proud of that rope all the same. Oh!”

Jem uttered a dismal groan.

“Are you hurt, Jem?”

“Hurt, sir! I just am hurt—horrible. ’Member when I fell down and the tub went over me?”

“And broke your ribs, and we thought you were dead? Yes, I remember.”

“Well, I feel just the same as I did then. I went down and a lot of ’em fell on me, and I was kicked and jumped on till I’m just as if all the hoops was off my staves, Mas’ Don; but that arn’t the worst of it, because it won’t hurt me. I’m a reg’lar wunner to mend again. You never knew any one who got cut as could heal up as fast as me. See how strong my ribs grew together, and so did my leg when I got kicked by that horse.”

“But are you in much pain now?”

“I should just think I am, Mas’ Don; I feel as if I was being cut up with blunt saws as had been made red hot first.”

“Jem, my poor fellow!” groaned Don.

“Now don’t go on like that, Mas’ Don, and make it worse.”

“Would they give us a candle, Jem, do you think, if I was to knock?”

“Not they, my lad; and I don’t want one. You’d be seeing how queer I looked if you got a light. There, sit down and let’s talk.”

Don groped along by the damp wall till he reached the place where his companion lay, and then went down on his knees beside him.

“It seems to be all over, Jem,” he said.

“Over? Not it, my lad. Seems to me as if it’s all just going to begin.”

“Then we shall be made sailors.”

“S’pose so, Mas’ Don. Well, I don’t know as I should so much mind if it warn’t for my Sally. A man might just as well be pulling ropes as pushing casks and winding cranes.”

“But we shall have to fight, Jem.”

“Well, so long as it’s fisties I don’t know as I much mind, but if they expect me to chop or shoot anybody, they’re mistook.”

Jem became silent, and for a long time his fellow-prisoner felt not the slightest inclination to speak. His thoughts were busy over their attempted escape, and the risky task of descending by the rope. Then he thought again of home, and wondered what they would think of him, feeling sure that they would believe him to have behaved badly.

His heart ached as he recalled all the past, and how much his present position was due to his own folly and discontent, while, at the end of every scene he evoked, came the thought that no matter how he repented, it was too late—too late!

“How are you now, Jem?” he asked once or twice, as he tried to pierce the utter darkness; but there was no answer, and at last he relieved the weariness of his position by moving close up to the wall, so as to lean his back against it, and in this position, despite all his trouble, his head drooped forward till his chin rested upon his chest, and he fell fast asleep for what seemed to him only a few minutes, when he started into wakefulness on feeling himself roughly shaken.

“Rouse up, my lad, sharp!”

And looking wonderingly about him, he clapped one hand over his eyes to keep off the glare of an open lanthorn.