Chapter 29 | An Unwelcome Recognition | The Adventures of Don Lavington

“It arn’t bad,” said Jem; “but it’s puzzling.”

“What is?” said Don, who was partaking of broiled fish with no little appetite.

“Why, how savages like these here should know all about cooking.”

The breakfast was eaten with an admiring circle of spectators at hand, while Ngati kept on going from Don to his tribesmen and back again, patting the lad’s shoulder, and seeming to play the part of showman with no little satisfaction to himself, but with the effect of making Jem wroth.

“It’s all very well, Mas’ Don,” he said, with his mouth full; “but if he comes and says ‘my pakeha’ to me, I shall throw something at him.”

“Oh, it’s all kindly meant, Jem.”

“Oh, is it? I don’t know so much about that. If it is, why don’t they give us back our clothes? Suppose any of our fellows was to see us like this?”

“I hope none of our fellows will see us, Jem.”

“Tomati Paroni! Tomati Paroni!” shouted several of the men in chorus.

“Hark at ’em!” cried Jem scornfully. “What does that mean?”

The explanation was given directly, for the tattooed Englishmen came running up to the whare.

“Boats coming from the ship to search for you,” he said quickly, and then turned to Ngati and spoke a few words with the result that the chief rushed at the escaped pair, and signed to them to rise.

“Yes,” said the Englishman, “you had better go with him and hide for a bit. We’ll let you know when they are gone.”

“Tell them to give us our clothes,” said Jem sourly.

“Yes, of course. They would tell tales,” said the Englishman; and he turned again to Ngati, who sent two men out of the whare to return directly with the dried garments.

Ngati signed to them to follow, and he led them, by a faintly marked track, in and out among the trees and the cleared patches which formed the natives’ gardens, and all the while carefully avoiding any openings through which the harbour could be seen.

Every now and then he turned to speak volubly, but though he interpolated a few English words, his meaning would have been incomprehensible but for his gestures and the warnings nature kept giving of danger.

For every here and there, as they wound in and out among the trees, they came upon soft, boggy places, where the ground was hot; and as the pressure of the foot sent hissing forth a jet of steam, it was evident that a step to right or left of the narrow track meant being plunged into a pool of heated mud of unknown depth.

In other places the hot mud bubbled up in rounded pools, spitting, hissing, and bursting with faint cracks that were terribly suggestive of danger.

Over these heated spots the fertility and growth of the plants was astounding. They seemed to be shooting up out of a natural hothouse, but where to attempt to pass them meant a terrible and instant death.

“Look out, Mas’ Don! This here’s what I once heard a clown say, ‘It’s dangerous to be safe.’ I say, figgerhead, arn’t there no other way?”

“Ship! Men! Catchee, catchee,” said Ngati, in a whisper.

“Hear that, Mas’ Don? Any one’d think we was babbies. Ketchy, ketchy, indeed! You ask him if there arn’t no other way. I don’t like walking in a place that’s like so much hot soup.”

“Be quiet, and follow. Hist! Hark!”

Don stopped short, for, from a distance, came a faint hail, followed by another nearer, which seemed to be in answer.

“They’re arter us, sir, and if we’re to be ketched I don’t mean to be ketched like this.”

“What are you going to do, Jem?”

“Do?” said Jem, unrolling his bundled-up clothes, and preparing to sit down, “make myself look like an ornery Chrishtun.”

“Don’t sit down there, Jem!” cried Don, as Ngati gave a warning cry at the same moment, and started back.

But they were too late, for Jem had chosen a delicately green mossy and ferny patch, and plumped himself down, to utter a cry of horror, and snatch at the extended hands. For the green ferny patch was a thin covering over a noisome hole full of black boiling mud, into which the poor fellow was settling as he was dragged out.

“Fah!” ejaculated Jem, pinching his nose. “Here, I’ve had ’most enough o’ this place. Nice sort o’ spot this would be to turn a donkey out to graze. Why, you wouldn’t find nothing but the tips of his ears to-morrow morning.”

Another hail rang out, and was answered in two places.

“I say, Mas’ Don, they’re hunting for us, and we shall have to run.”

He made signs to the chief indicative of a desire to run, but Ngati shook his head, and pointed onward.

They followed on, listening to the shouts, which came nearer, till Ngati suddenly took a sharp turn round a great buttress of lava, and entered a wild, narrow, forbidding-looking chasm, where on either side the black, jagged masses of rock were piled up several hundred feet, and made glorious by streams which coursed among the delicately green ferns.

“Look’s damp,” said Jem, as Ngati led them on for about fifty yards, and then began to climb, his companions following him, till he reached a shelf about a hundred feet up, and beckoned to them to come.

“Does he think this here’s the rigging of a ship, and want us to set sail?” grumbled Jem. “Here, I say, what’s the good of our coming there?”

The chief stamped his foot, and made an imperious gesture, which brought them to his side.

He pointed to a hole in the face of the precipice, and signed to them to go in.

“Men—boat,” he said, pointing, and then clapping his hand to his ear as a distant hail came like a whisper up the gully, which was almost at right angles to the beach.

“He wants us to hide here, Jem,” said Don; and he went up to the entrance and looked in. A hot, steamy breath of air came like a puff into his face, and a strange low moaning noise fell upon his ear, followed by a faint whistle, that was strongly suggestive of some one being already in hiding.

“I suppose that’s where they keeps their coals, Mas’ Don,” said Jem. “So we’ve got to hide in the coal-cellar. Why not start off and run?”

“We should be seen,” said Don anxiously. “Don’t let us do anything rash.”

“But p’r’aps it’s rash to go in there, my lad. How do we know it isn’t a trap, or that it’s safe to go in?”

“We must trust our hosts, Jem,” replied Don. “They have behaved very well to us so far.”

There was another hail from the party ashore, and still Jem hesitated.

“I don’t know but what we might walk straight away, Mas’ Don,” he said, glancing down at the garb he wore. “If any of our fellows saw us at a distance they’d say we was savages, and take no notice.”

“Not of our white faces, Jem? Come, don’t be obstinate; I’m going on.”

“Oh, well, sir, if you go on, o’ course I must follow, and look arter you; but I don’t like it. The place looks treacherous. Ugh! Wurra! Wurra! Wurra!”

That repeated word represents most nearly the shudder given by Jem Wimble as he followed Don into the cave, the chief pointing for them to go farther in, and then dropping rapidly down from point to point till he was at the bottom, Jem peering over the edge of the shelf, and watching him till he had disappeared.

“Arn’t gone to tell them where we are, have he, Mas’ Don?”

“No, Jem. How suspicious you are!”

“Ah, so’ll you be when you get as old as I am,” said Jem, creeping back to where Don was standing, looking inward. “Well, what sort of a place is it, Mas’ Don?”

“I can’t see in far, but the cavern seems to go right in, like a long crooked passage.”

“Crooked enough, and long enough,” grumbled Jem. “Hark!”

Don listened, and heard a faint hail.

“They’re coming along searching for us, I suppose.”

“I didn’t mean that sound; I meant this. There, listen again.”

Don took a step into the cave, but went no farther, for Jem gripped his arm.

“Take care, my lad. ’Tarn’t safe. Hear that noise?”

“Yes; it is like some animal breathing hard.”

“And we’ve got no pistols nor cutlashes. It’s a lion, I know.”

“There are no lions here, Jem.”

“Arn’t there? Then it’s a tiger. I know un. I’ve seen ’em. Hark!”

“But there are no tigers, nor any other fierce beasts here, Jem.”

“Now, how can you be so obstinate, Mas’ Don, when you can hear ’em whistling, and sighing and breathing hard right in yonder. No, no, not a step farther do you go.”

“Don’t be so foolish, Jem.”

“’Tarn’t foolish, Mas’ Don; and look here: I’m going to take advantage of them being asleep to put on my proper costoom, and if you’ll take my advice, you’ll do just the same.”

Don hesitated, but Jem took advantage of a handy seat-like piece of rock, and altered his dress rapidly, an example that, after a moment or two of hesitation, Don followed.

“Dry as a bone,” said Jem. “Come, that’s better. I feels like a human being now. Just before I felt like a chap outside one of the shows at our fair.”

He doubled up the blanket he had been wearing, and threw it over his arm; while Don folded his, and laid it down, so that he could peer over the edge of the shelf, and command the entrance to the ravine.

But all was perfectly silent and deserted, and, after waiting some time, he rose, and went a little way inside the cavern.

“Don’t! Don’t be so precious rash, Mas’ Don,” cried Jem pettishly, as, urged on by his curiosity, Don went slowly, step by step, toward what seemed to be a dark blue veil of mist, which shut off farther view into the cave.

“I don’t think there’s anything to mind, or they wouldn’t have told us to hide here.”

“But you don’t know, my lad. There may be dangerous wild critters in there as you never heard tell on. Graffems, and dragons, and beasts with stings in their tails—cockatoos.”

“Nonsense! Cockatrices,” said Don laughing.

“Well, it’s all the same. Now, do be advised, Mas’ Don, and stop here.”

“But I want to know what it’s like farther in.”

Don went slowly forward into the dim mist, and Jem followed, murmuring bitterly at his being so rash.

“Mind!” he cried suddenly, as a louder whistle than ordinary came from the depths of the cave, and the sound was so weird and strange that Don stopped short.

The noise was not repeated, but the peculiar hissing went on, and, as if from a great distance, there came gurglings and rushing sounds, as if from water.

“I know we shall get in somewhere, and not get out again, Mas’ Don. There now, hark at that!”

“It’s only hot water, the same as we heard gurgling in our bath,” said Don, still progressing.

“Well, suppose it is. The more reason for your not going. P’r’aps this is where it comes from first, and nice place it must be where all that water’s made hot. Let’s go back, and wait close at the front.”

“No; let’s go a little farther, Jem.”

“Why, I’m so hot now, my lad, I feel as if I was being steamed like a tater. Here, let’s get back, and—”

“Hist!”

Don caught his arm, for there was another whistle, and not from the depths of the dark steamy cave, but from outside, evidently below the mouth of the cave, as if some one was climbing up.

The whistle was answered, and the two fugitives crept back a little more into the darkness.

“Ahoy! Come up here, sir!” shouted a familiar voice, and a hail came back.

“Here’s a hole in the rocks up here,” came plainly now.

“Ramsden,” whispered Don in Jem’s ear.

They stole back a little more into the gloom, Jem offering no opposition now, for it seemed to them, so plainly could they see the bright greenish-hued daylight, and the configuration of the cavern’s mouth, that so sure as any one climbed up to the shelf and looked in they would be seen.

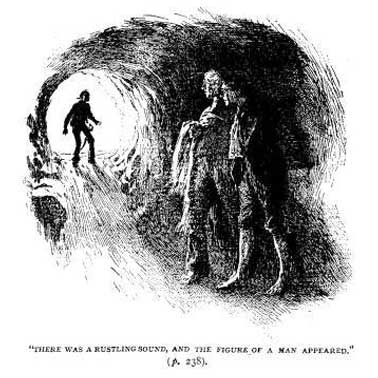

Impressed by this, Don whispered to Jem to come farther in, and they were about to back farther, when there was a rustling sound, and the figure of a man appeared standing up perfectly black against the light; but though his features were not visible, they knew him by his configuration, and that their guess at the voice was right.

“He sees us,” thought Don, and he stood as if turned to stone, one hand touching the warm rocky side of the cave, and the other resting upon Jem’s shoulder.

The man was motionless as they, and his appearance exercised an effect upon them like fascination, as he stood peering forward, and seeming to fix them with his eyes, which had the stronger fancied effect upon them for not being seen.

“Wonder whether it would kill a man to hit him straight in the chest, and drive him off that rock down into the gully below,” said Jem to himself. “I should like to do it.”

Then he shrank back as if he had been struck, for the sinister scoundrel shouted loudly,—

“Ahoy there! Now, then out you come. I can see you hiding.”