Chapter 1 | A Young Hero

Dr Martin wore a close-fitting black silk cap.

Why?

Well, the answer to the old riddle, “Why does a miller wear a white hat?” is, “To keep his head warm.”

That answer would do for a reply to the question why this grey, anxious-looking Dr Martin wore a close-fitting black silk cap as he sat poring over an old book opposite Phil Carleton, who also bent over a book; but he was not reading, for he had a pencil in his fingers and a sheet of paper covering one page, upon which sheet he was making notes.

Not a single one, for Phil was not far enough advanced for such work as that. He was drawing, after a fashion, and very busily, when the old Doctor, his tutor, suddenly looked up.

“Now, my dear boy,” he said, “can you say that declension?”

Phil started and shut up the book suddenly, turning very red the while.

“Don’t you know it yet?” said the Doctor, gravely.

The boy shook his head and looked terribly confused.

“Then you cannot have been studying it. What have you there?”

The Doctor spoke like a Frenchman, and said dere.

“Ah,” he continued, reaching out his hand and drawing out the paper. “I see, drawing-soldiers, eh?”

Phil nodded.

“Vairy fonnee soldiers, my boy. I should not know but for this sword. And is this a gun?”

Phil nodded again.

“Ah,” said the old French-Canadian, “it is a pity you think so much of soldiers. You should learn your lesson.”

“I’m going to be a soldier—some day,” said Phil.

“Ah, yes, some day. Like my dear old friend, your father,” said the Doctor, with a sigh.

“Yes,” cried the boy, eagerly. “Is he coming to see me, Dr Martin?”

“Why do you ask? Are you not happy here?”

“Not very,” said the boy, sadly.

“Ah, I am sorry. What is the reason? There, speak out.”

The boy hesitated for a few moments, and then burst out with, “It’s because of the Latin, and what Pierre said.”

“Ah, the Latin is hard, my child; but if you work hard it will grow easy. But tell me; what does Pierre say?”

“He says the French are going to fight the English and drive them out of the country, and my father is sure to be killed.”

“Pierre is a bad, cruel boy to speak to you like that. He deserves the stick.”

“Then there is not going to be any fighting, Dr Martin?”

The old man shook his head.

“I am afraid,” he said, sadly. “Perhaps you ought to know, my child. The English troops are advancing against the city yonder, and I am very anxious. I am hoping every day to obtain some news from your father—a letter or a message, to tell me what to do. It is unfortunate that we should be staying here among my people and war to begin.”

“Then there is going to be fighting?” cried the boy.

“I fear so, my boy.”

“Then I know.”

“You know what, Phil?”

“My father will come and fetch me.” The old man shook his head.

“He is with his regiment, my child, and could not come away.”

The old man stopped short, for the door was suddenly thrown open, and a big, heavy-looking boy of seventeen or eighteen came hurriedly in.

“Some one wants you, Uncle Martin,” he cried.

“Yes, quite right,” came in a sharp, short, military tone. “That will do, my young friend. Thanks.”

The speaker, a tall bronzed personage in plain clothes, strode into the room, held the door open, and signed to the big lad to pass out, which he did slowly and unwillingly, but not before he had heard Phil utter the one word, “Father!” as he sprang forward to fling his arms round the visitor’s waist.

“My boy!” was the response. Then to the Doctor, “That’s unlucky! But that boy does not understand English?”

The Doctor shook his head.

“I am afraid he does, quite well enough to grasp who you are.”

“Tut! tut! tut!” ejaculated the visitor. “But tell me; are there any troops near here?”

“Many, a few miles away,” said the Doctor.

“But he is not likely to go and tell them that there is an Englishman here?”

“I hope not. Oh, no; I will see that he does not. Then there is risk in your coming here, my friend?”

“I’m afraid so; but I was obliged to come, Martin.”

“But, father, why have you not come in your uniform?”

“Quiet, boy,” was the reply; “I have no time to explain. Look here, Martin, old friend; when I agreed that Phil here should come on this long visit with you I had no idea that matters would turn out like this. But there is no time to waste. You must get out of the country as fast as you can.”

“With your son?”

“Of course. Get south, beyond the English lines. You understand?”

“Yes. Quite.”

“Then now get me something; bread and meat or bread and water—I am nearly starved.”

“You’ll have dinner with us, father?” cried Phil.

“No, my boy; I must be off at once.”

“Oh, father, take me with you,” cried Phil, piteously.

“I cannot, my boy. I must get back to my regiment, and at once.”

“So soon?” said the old Doctor, sadly.

“Yes, so soon. If it got about that I was here I should be seized and shot for a spy.”

“Father!” cried Phil, clinging to him.

“But I am not going to be caught, nor shot neither, my boy,” cried the Captain, raising him on a chair so that they stood face to face.

“And you’ll take me with you, father?”

“Impossible, boy. Come, be a man. You shall join me soon, but I cannot take you with me. Dr Martin will bring you.”

“But, father—”

“Phil, what have I always taught you?” cried the Captain.

“To—to—be obedient.”

“That’s right. Now, do you want to help me?”

“Yes, father. So much.”

“Then listen to all I say. Now, Doctor,” continued the Captain, “I have ventured into the enemy’s camp—not as a spy, but to see you and my boy. I dare not stay ten minutes before I hurry back to join our people.”

“Then the English forces are near?” said the old Doctor, excitedly.

“That is not for you to know or question me upon. It is enough if I tell you that this is no place for my son, and if things go against us you will take him back to England. You promise that?”

“I have promised it, Carleton. I have all your old instructions, and come what may I will deliver him safely into the hands of your relatives and friends.”

“I am satisfied, Doctor,” said the Captain, huskily, “and I shall go back to my regiment in peace. Now then, the bread and meat I asked for—quick! And you will see that the lad who showed me in does not leave the place till I have been an hour upon my road? I must have that start, for my poor horse is pretty well done up.”

The Doctor made no reply, but hurried out of the room, leaving father and son together, when the Captain laid his hands upon his son’s shoulders.

“That was all very brave and well done, my boy,” he said. “Now I am going away quite at rest about you, for I know that you will do as you have promised.”

“Yes, father. But—”

“But what, Phil?”

“Oh, do, pray—pray, take me with you!”

Captain Carleton winced, and his hands tightened upon the boy’s shoulders, while his voice sounded husky as he spoke.

“Phil,” he said, “do you know what I am?”

“Yes, a soldier; one of the King’s captains, father.”

“Right, boy; and didn’t I tell you that a soldier must always do his duty?”

“Yes, father.”

“And that boys must always do theirs? Well, sir, the King says I must march with the army at once, and I say you must do your duty too.”

“Yes, father,” said Phil, in a choking voice, “and I will.”

“Spoken like a man.”

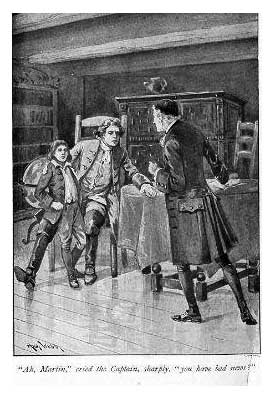

At that moment the door was re-opened hurriedly.

“Ah, Martin,” cried the Captain, sharply, “you have bad news?”

“Yes—that lad Pierre has gone across the fields towards the town.”

“Where the French soldiers are stationed?”

“Yes.”

“Then I have no time to lose. The bread—the meat!”

“I—I—” faltered the old man.

“Thought only of my safety,” said the Captain. “Here, stop! Phil! Where are you going?”

But the boy dashed through the open door, which swung to behind him.

“Call him back,” cried the Captain, excitedly. “I must say good-bye, for we may never meet again. Stop; I am weak enough without that. I ought not to have come. Martin, old friend, remember. I trust you, and if fate makes him an orphan—”

“You have known me all these years, Carleton, and I have grown to love him as if he was my own. Trust me still, and—”

There was a quick footstep, the door was kicked open, and Phil rushed in, panting and flushed, with a large loaf under one arm and a basket in his hand, out of which the crisp brown legs of a roast chicken were sticking.

“Here, father!” he cried.

“Bravo! Good forager,” cried the Captain, snatching the provisions from the boy to throw on the table before clasping Phil to his breast in one quick, tight embrace.

The next minute he had thrust the little fellow into the Doctor’s arms.

“Remember!” he cried aloud, and catching up basket and loaf, he bounded out of the open window and ran across the garden to the yard, where he had left his horse tethered to a post.

It seemed directly after that Phil was standing on the window-sill waving his hand and shouting, “Good-bye—good-bye, father!”

But his words were not heard by the Captain, who was urging his tired horse into a gallop.

It was none too soon, for a body of soldiers were coming at the double from the direction of the town, and with a cry of rage the boy whispered through his teeth:

“Look, there’s Pierre running to show them the way!”

“Hush! Quick, Phil; we must go.”

“After father?” cried the boy, joyously.

“No; we must make for the woods.”

The old man hurried out by the back door, and then keeping under the shelter of fence and hedge, they made for a patch of woodland, which hid them from the Captain’s pursuers.

“Let’s wait here for a few moments to get breath,” panted the old man.

As he spoke there was the report of a musket, followed by a scattered series of shots.

“What’s that?” whispered Phil, excitedly. “I know; but they can’t hit father, he’s riding away too fast. Do you think they’ll shoot after us? I wish I had a gun.”

“Why?” said the Doctor, smiling.

“Because I feel as if I should like to shoot at Pierre.”