Chapter 7 | Our Soldier Boy

In a month’s time, in spite of weakness, the Colonel had sufficiently recovered to resume the command of his regiment, and Dick was the hero and idol of the men.

But poor Mrs Corporal Beane was jealous and unhappy—jealous because the Colonel made so much of Dick; unhappy on account of the Corporal, whose recovery was very slow. But the Colonel, she owned, behaved very well to her. He said that he would not interfere much, as he looked upon herself as the boy’s mother, but sooner or later they would find out who Dick’s parents were, and that he should stay with the regiment, but he must be looked after well.

“As if he could be looked after better,” Mrs Corporal said to her invalid husband. “I do look after you well, Dick, don’t I?”

“Yes, mother; of course you do,” said the boy.

“And love you too; and you love me and father, don’t you?”

“Why, you know I do,” said the boy, laughing, “and Colonel Lavis sent for the tailor this morning, and I was measured for a new uniform like the men in the band.”

“Bless us and save us!” cried Mrs Beane. “Well, that is handsome of him, but like a drummer, Dick, not with gold lace?”

“Yes, scarlet and gold,” said the little fellow proudly; “and I’m to learn to play.”

It would be a long story to tell of the terrible fights the 200th were in all through that terrible Peninsular War: but Dick was with the regiment and through it all, not fighting, but with the doctor and the men whose duty it was to look after the wounded, and many were the blessings called down upon the head of the brave boy, who seemed to bear a charmed life, as he ran here and there with water to hold to the lips of the poor fellows who were stricken down.

But all things have an end, the bad like the good, and in the days of peace the 200th were being feasted at one of the towns by the Portuguese gentry and some of the English merchants who had been nearly ruined by the war.

Dick was in it all, for he was strong and well as could be—happy too as a boy, but his memory was still a perfect blank about the past. He could recall everything which had happened since he was nursed back to health and strength, but nothing more; and poor Corporal Joe, who was never likely to be able to join the ranks again, and only too grateful at being allowed to act as the Colonel’s servant, never mentioned to the boy the day when he found him up at the burning house.

“Only set him thinking about them murdering camp-followers, missus, and make him unhappy, and we don’t want that, do us?”

“No, Joe, dear,” she cried; “I should think we don’t.”

And so the time had nearly come for the remnant to march to the port and embark for England, when a farewell party was given to the officers by a Mr and Mrs Trevor, the principal merchant and his lady, and out of compliment the Colonel and officers sent the band up to the mansion to play in the garden during dinner, Dick being told that he might go with the musicians to see the sight.

Everyone of note was there, and the sight was grand in the lit-up grounds. There was feasting and speech-making and thanks given to the brave men who had saved the country from the oppressor, and the Colonel returned thanks.

It was just then that the band-master turned to Dick and said:—

“Go up to the Colonel and ask him if we shall play the dance music now.”

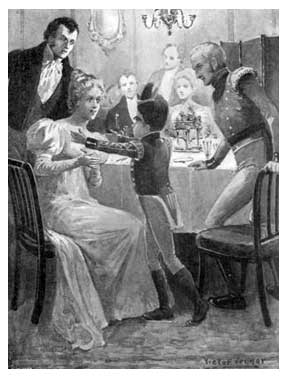

The band was stationed by one of the open windows, and Dick, in his best uniform, had only to step in and go round behind the Colonel’s chair to whisper to him.

“Ah, Dick, my boy,” he said. “Dance music? Yes. Stop; I’ll ask our hostess. By the way, Mrs Trevor,” he said, turning to the tall, sad-looking lady at whose side he was sitting, “let me introduce to you the greatest man in our corps, the brave little fellow who saved my life.”

Mrs Trevor turned smilingly round, when a sunburned gentleman on her other side gave utterance to a gasp and sprang from his chair.

“My dear madam,” cried the Colonel, “are you ill?”

For Mrs Trevor uttered a wild cry, as, to the astonishment of all, the little fellow in scarlet and gold sprang to her side and threw his arms about her neck.

“Oh, mother! Why, father,” he cried, “do you live here?”

The boy’s memory of the past had come back like a flash of light, and as he caught at Mr Trevor’s hand he suddenly turned pale, shivered, and clapped his hands to the scar upon his head, for the horror of the scene before he was struck down by one of a gang of French camp-followers came back to him with terrible vividness.

The banquet was nearly at an end when this scene took place and after warm congratulations from the visitors, they had the good taste to hurry away, and the band was dismissed, the Colonel only stopping with the boy to help him relate how he was retained in the regiment.

He heard in return an explanation from Mr Trevor, who told how it was that the burned house was their country villa among the mountains, where in ignorance of danger being near, the boy was left with the servants for a few hours, the father and mother returning to find only smoking ruins and the traces of a horrible massacre having taken place. So convinced were they that their son had perished in the fire with the servants that no search was made, and the Trevors fled, glad to escape with their lives, Mr Trevor having a hard task to restore his wife to reason after the terrible shock.

To them their child was dead, and they had felt that they would never thoroughly recover from the dreadful blow.

“But you see, Colonel, one never knows what is in store, and it is not right to despair. Now, how can we thank you enough for all that you have done?”

“I don’t want thanks,” said the Colonel. “I ought to thank you for all that he so bravely did for me; and besides, Dick, boy, there was someone else who—”

He stopped, for a servant entered the room.

“I beg pardon, sir, but there’s a woman and a soldier outside. I told them you were engaged, but the woman said she would see you.”

“A woman and a soldier?” cried Mr Trevor—“will see me?”

“I know,” cried Dick excitedly, “it’s mother and father—I mean—I—”

He too stopped short, and looked from one to the other. “I mean,” he cried bravely, “my other father and mother, who saved me and brought me back to life.”

“Where is he?” cried an angry voice in the hall. “I will see him. Dick, my darling Dick!”

Mrs Trevor turned white, and a pang shot through her, as she saw her newly-recovered son rush to the door, throw it open and call out loudly:—“Here I am, mother: this way.”

“Oh, my darling!” cried Mrs Corporal: “I’ve just heard—Oh, what does it mean? I—I beg your pardon, my lady, and you too, sir, and Colonel, but—but they’ve been telling me—”

“Yes, it’s all true,” cried Dick, interrupting her. “Mother dear, this is my other mother, and father dear, this is Corporal Joe.”

“Oh—oh—oh!” sobbed Mrs Corporal wildly; “after all this time, and me getting to love him and look upon him as my own! Oh, my lady, my lady, you never would be so cruel as to take him away? It would be so wicked, so hard upon us now.”

“My own boy?” said Mrs Trevor gently, as Dick stood gazing wildly from one to the other.

“But for us never to see him again,” cried Mrs Corporal fiercely, and she caught the boy by the arm. “Don’t say you won’t love us still, Dick dear!”

“Why should he say such cruel words to one who has been a second mother to him,—to one who brought him back to life? And why should you never see him again? We are going to England too, and while we have a home it shall be yours as well.”

Mrs Trevor took the rough woman’s hand, leaned towards her, and kissed her cheek.

“For saving my darling’s life,” she said softly, and then burst into tears.

Poor Mrs Corporal’s anger melted at this, and she caught Mrs Trevor’s hand in hers and kissed it again and again.

“Oh, my dear lady,” she sobbed; “I’m a wicked, selfish woman, and he is your own flesh and blood. Come with you to be where I could always see the dear, brave, darling boy? Oh, I’d go down on my knees and be thankful, but I can’t leave my poor man. I wouldn’t if he was strong and well, and now he’s wounded and broken and got to leave the regiment—no, not if we had to beg our bread from door to door. Kiss me, my darling boy, once more, and then—oh Joe, my man, I can’t bear it! Take me away, take me away.”

Joe, who had stood back stiffly in the background near where Dick’s father was whispering with Colonel Lavis, took two steps to the front with a painful limp, saluted the company, and caught his half-blind wife in his arms.

“It’s quite right, my lass,” he said huskily, “and—from my heart, my lady, I say thank God the dear lad’s coming to his own. Don’t mind what the missus said—she—she, you see, loved him, and—good-bye, Master Dick, my lad—good—”

“Stop,” said Mr Trevor, stepping towards him with his eyes moist, and clapping the invalided soldier on the shoulder. “Corporal, your Colonel says that you are as brave and true a man as ever stepped. I feel that it must be so. While I live the wounded soldier to whom we owe so much shall never want a home. Dick, as they call you—Frank, my boy, what do you say to this?”

“Say?” faltered the boy, as he stood trembling, and then he could not speak. The next moment he had rushed to his mother to kiss her passionately, giving her a look that seemed to say, “Don’t think I shall not love you more than ever;” and then he ran and caught Joe’s hand, holding it fast for a moment, before flinging his arms about poor Mrs Corporal’s neck, to whisper something in her ear which made the poor woman wipe away her tears.

“Hah!” cried the Colonel huskily, “this is peace indeed.”

That night mother and father stole hand in hand into the room next their own, where their son lay sleeping peacefully. They did not bend down to kiss him lest he should start awake, but they knelt by his side in thankfulness for the great joy which filled their hearts, before thinking sadly of those to whom they owed so much.

Strangely enough, just about the same time Mrs Corporal rose from her knees and said:—

“There, Joe, old man, I won’t cry another drop, for I feel now that it’s right and what should be. But just in here somewhere there’s a little place where he’ll always seem to be—our soldier boy to the very end.”