Chapter 16 | The Passage That Is Too Secret | The Young Castellan

“Going, Roy?” said Lady Royland to her son, as he rose from his seat in the library that night about an hour after Master Pawson had gone to his room, retiring early on the plea of a bad headache.

“Yes, mother; I’m going my rounds.”

Lady Royland sighed.

“It seems very hard on you, my boy—all this work and watching.”

“Oh, I don’t mind,” said the lad, smiling; “I’ve got used to it already. It makes everything go so regularly, and I feel sure that I have done everything to make the place safe.”

“But it is hard upon the sentries, who, but for this, would be peacefully sleeping in their beds.”

“Do us all good, mother. Good-night.”

There was an affectionate embrace, and Roy went to his room, buckled on his sword, put on his helmet, threw a large cloak over his shoulders, and then went down to the guard-room door in the great lower gate-way, to be challenged at once, and forced to give the word.

A faint light shone out from the open door upon the military figure on duty, and Roy recognised in him one of the men from the mill, completely transformed from the heavy plodding fellow who had come in to take service.

But the challenge had brought out the old sergeant, also in a cloak, although it was a hot night, and within it he swung a lighted lantern.

The drawbridge was up and the portcullis down, making the entrance look black and strange, and shutting off the outer gate, from which the day guard was withdrawn, though this had not been accomplished without trouble and persuasion, for old Jenkin had protested.

“Like giving up the whole castle to the enemy, Master Roy,” he said, with a full sense of the importance of his little square tower, and quite ignoring the fact that in the event of trouble he would be entirely cut off from his fellows if the drawbridge was raised.

But the old man gave in.

“Sodger’s dooty is to ’bey orders,” he said; and with the full understanding that he was to go back to his gate in the morning, he came into the guard-room to sleep on a bench every night.

“How is old Jenk?” said Roy.

“Fast asleep in his reg’lar place,” replied Ben, and he led the way back into the gloomy stone guard-room, where he held up the lantern over the venerable old fellow’s face, and Roy looked at him thoughtfully.

“Seems hard to understand it, Master Roy, don’t it?” said Ben; “but if we lives, you and me’ll grow to be as old as that. I expect to find some morning as he’s gone off too fast ever to wake up again.”

“Poor old fellow!” said Roy, laying his gloved band gently on the grey head. “How fond he always was of getting me to his room when I could only just toddle, and taking me to the moat to throw bread to the carp.”

“Fished you out one day, didn’t he, Master Roy!”

“To be sure, yes; I had almost forgotten that. I had escaped from the nurse and tumbled in.”

“Ah! he’s been a fine old fellow,” said Ben. “I used to think he was a great worry sticking out for doing this and doing that, when he wasn’t a bit of good and only in the way; but somehow, Master Roy, I began to feel that some day I might be just as old and stupid and no more use, and that made me fancy something else.”

“What was that, Ben?” said Roy, for the old soldier had paused.

“Well, sir, I began to think that I was growing into a vain old fool after all, or else I should have seen that old Jenk was perhaps of more use here than I am. Can’t you see, Master Roy?”

“I can’t see what you mean, Ben.”

“Why, that old chap’s about the finest sample of a reg’lar soldier that these young fellows can have. I believe if the enemy did come, that old man would draw the sword that shakes in his weak old hand, and march right away to meet ’em as bravely as the best here.”

“I’m sure he would, Ben,” said Roy, warmly.

“Then he’s one of our best men still, sir. Come on—I mean give the order, sir, and let’s go our rounds.”

Then, in the silence of the dark night, Roy led the way to the winding stair, and mounted silently to the ramparts, closely followed by Ben with the blinded lantern, and on reaching the top, they walked on to the left to the south-west tower; but before they could reach it a firm voice challenged them from the top. Then after giving the pass they went on through the tower and out onto the western ramparts, turning now to where the north-west tower loomed up all in darkness.

“Master Pawson’s abed, sir,” whispered Ben.

“Yes; not well,” was the reply, in the same low tone.

But there was no challenge from here, and Roy walked silently in at the arched door-way, passed the secretary’s door, and mounted the stair to severely admonish the sentry who was not keenly on the alert.

“Don’t let him off easy, Master Roy,” whispered Ben; “we might have been an enemy, sir, for aught he could tell.”

This was spoken with the sergeant’s lips to his young master’s ear, and a few moments later Roy was at the top of the little turret, and stood there in the door-way ready to pounce upon the man whom he expected to find asleep.

But to his great satisfaction the sentry was well on the alert, for he was kneeling at one of the crenelles, reaching out as far as he could, and evidently watching something away to the north, while all was so still and dark that the movement of a fish or water-rat in the deep moat below sounded loud and strange.

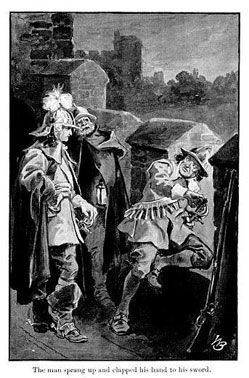

Roy stepped out silently, crossed the narrow leads, and  stood looking in the same direction as the sentinel; but he could make out nothing, and he was about to speak when the man, who had suddenly divined his presence, sprang up and clapped his hand to his sword.

stood looking in the same direction as the sentinel; but he could make out nothing, and he was about to speak when the man, who had suddenly divined his presence, sprang up and clapped his hand to his sword.

“Stand!” he cried, hoarsely.

Roy gave the word, and Ben stepped out of the door-way to his side.

“Why, sir, you quite scared me,” faltered the man; “I didn’t hear you come.”

“You should have heard,” said Roy, sternly. “What were you watching there?”

“That’s what I don’t know, sir. I see a light out yonder somewheres about where them old stones is on the hill. And then I thought I heard talking, but that’s quarter of an hour ago.”

Both Roy and his companion had a good long look, but there was nothing to see or hear; and after admonishing the man to keep an eye upon the place, they descended and visited the sentries on the north-east and south-east towers, to find them well upon the qui vive.

After this they descended, and Ben led the way to the armoury, where he set the lantern on the table, took a spare candle from a box, and a bunch of keys from a drawer.

“May mean nothing, Master Roy; but I don’t understand what light there could be up nigh the old chapel ruins, nor who could be talking there at this time of night.”

“Not likely to be anything wrong, Ben, because if they had been enemies, they would not have shown a light.”

“Signal perhaps, sir.”

“Well, they wouldn’t have talked aloud.”

“Don’t suppose they did, sir. Sound runs in a still, dark night like this. Well, anyways it seems to me as it’s quite time we had a good look round to see if there’s a hole anywhere in the bottom of the pot, so if you’re ready, so am I. Only say the word.”

“Forward!” cried Roy; and, going first with the lantern, Ben led the way along the corridor to the head of a flight of stone steps, down which they went to the underground passage, which with groined roof ran right along all four sides of the castle. The dark place seemed full of whispering echoes, as they went on past door after door leading into cellar and dungeon, all now turned into stores; for the great mass of provender brought in by Farmer Raynes’s wagons had here been carefully packed away, the contents of each place being signified by a white, neatly painted number, duly recorded in a book where the account of what number so-and-so indicated was carefully written in Master Pawson’s best hand, since he had eagerly undertaken the duties of clerk.

At each corner of the castle basement, the passage expanded into a circular crypt with a huge stone pillar, many feet in diameter, in the middle, from which radiated massive arches to rest on eight smaller pillars. This radial series of arches supported one of the towers, and, after passing the one to the north-east, Ben led on with his lantern along the passage running to the tower at the north-west corner, the dim light casting strange shadows behind, which seemed to be moving in pursuit of the two silent figures, urged on by the whispering echoes of their steps.

The pavement was smooth and perfectly dry, as were the massive stone walls; and as they went on, Roy fell into a musing fit, and thought of what a strongly built place Royland castle was, and how in times of emergency, if a garrison were hard pressed and had to yield rampart and tower to a powerful enemy, they would still have these passages and crypts as a place of refuge from which, if a bold defence were made, it would be impossible to dislodge them.

Apparently mind does influence mind under certain circumstances, for, just as Roy had arrived at this point, Ben stopped short and turned.

“Look here, Master Roy,” he said, “you ought, now we’re getting in pretty good order, to do two things.”

“Yes; what are they?”

“Have that there stone gallows on the ramparts put a bit in order. It wants a few stones and some mortar.”

“Why should I have that put in order?” said Roy, shortly.

“Case you want to hang any traitors, sir, for giving notice to the enemy of what we’re doing, or trying to open the gates to ’em.”

“I shall never want to hang any traitors,” said Roy, sternly.

“I don’t s’pose you will, sir; but it’s just as well to let people see that you could if you wanted to. Might keep us from having any.”

“I will not let the garrison see that I could have any such mistrust of the men who have come bravely up to help to protect my father’s property.”

“Well, Master Roy, that sounds handsome, and I like the idea of it: it’s cheering-like to a man who tries to do his best. But all people don’t think same as we do, and whenever we hear of a castle being attacked and defended, there were always people outside trying to make traitors of those who were in, and temptation’s a nasty, cunning, ’sinuating sort of a thing. But you’re castellan, and you ought to do as you please.”

“I will, Ben, over that, at all events. Fancy what my mother would think if I were to be making preparations for such a horror.”

“Hum! yes, sir. What would she think? That’s a queer thing, Master Roy, isn’t it, what a deal mothers have to do with how a man does, whether he’s a boy or whether he’s growed up?”

“Why, of course they have. It is natural.”

“Yes, sir; I suppose it is,” said the old soldier, as he went on. “You wouldn’t think it, perhaps, of such a rough ’un as me, and at my time o’ life, but I never quite get my old woman out of my head.”

“I don’t see how any one could ever forget his mother,” said Roy, flushing a little.

“He can’t, sir,” said Ben, sharply; “what she taught him and said always sticks to the worst of us. The pity of it is, that we get stoopid and ashamed of it all—nay, not all, for it comes back, and does a lot of good sometimes, and—pst!—pst!—if we talk so loud we shall be waking Master Pawson. But I say, Master Roy, it won’t do, really. Look at that now!”

They were close to the circular crypt beneath the north-west tower, and Ben was holding up his lantern towards the curve of the arches on his left.

“Roots! coming through between the stones.”

“Yes, sir, that’s it. Only the trees her ladyship had planted, and that’s the beginning of pulling this corner of the castle down. There’s nothing like roots for that job. Cannon-balls’ll do it, and pretty quickly too; but give a tree time, and it’ll shake stone away from stone, and let the water come in, and then the frost freezes it, and soon it’s all over with the strongest tower ever made. Do ’ee now ask her to have ’em cut down, and the roots burned.”

“I’m not going to ask anything of the sort, Ben,” said Roy, shortly. “Now about this passage. You think it must run somewhere from here.”

“Yes, sir,” replied the old soldier, as he stood now under one of the arches of the crypt and raised his lantern to open a door. “There, now we can see a bit better. If there is such a place, it starts, I suppose, from somewhere here.”

He walked slowly round the place, holding the lantern into the recesses, eight of which appeared between the pillars surrounding that in the centre.

“But there’s plenty of room here for storing sacks or anything else, and you can have doors made to those two that haven’t got any, if you like.”

Roy walked into one of these recesses—cellar-like places of horse-shoe curve, going in a dozen feet, and then ending in a flat wall.

“Which way am I looking here, Ben?” said Roy.

“Out’ards, sir; you’re standing about level with the bottom of the moat, or pretty nigh thereabouts. You’re—yes—that’s where you are, just at the nor’-west corner, and the moat turns there.”

“Then the places on each side here face the moat, one to the north, the other to the west.”

“Well, not exactly, sir, but nearly.”

“Then the secret passage can’t begin at the end of either of these, and been built up.”

“I dunno, sir. Folk in the past as had to do with them passages did all they could to make ’em cunning.”

“But they couldn’t have made a passage through the moat.”

“Of course not, sir; it must have gone under it.”

“Then it couldn’t have started from here.”

“Why not, sir?” said Ben, with a low laugh; “what’s to prevent there being another dungeon like this on the other side of the wall there, one with a trap-door in it leading down ever so many steps into another place, and the passage begin ten or twenty foot deeper.”

“Something like the powder-magazine is made?”

“That’s it, sir. We’re in the lower part of a big round tower, and we know there’s those floors above us one on top of the other, and we don’t know that the old Roylands who built this place mayn’t have dug down and down before they started it, and made one, two, or three floors below where we stand.”

“What? Dug right down? Impossible!”

“They dug down that time as deep into the old stone to make the big well, sir.”

“Of course; then it is possible.”

“Possible, sir? Oh yes; look at the secret passages there are in some old walls, made just in the thickness, and doors leading into ’em just where you wouldn’t expect ’em to be. Up a chimney, perhaps, or a side of a window. I heered tell of one as was quite a narrow door, just big enough for a man to pass through, and you didn’t walk into it, because it wasn’t upright; but you got into it by crawling through a square hole with a thin stone door which fell back after you were through. Then you stood up, and could go half round the old house it was in.”

“Well,” said Roy, “if there is such a passage, we must find it; but if it has been built up, we might have to pull half the place down.”

“Yes, sir; but first of all, we’ll have a good look in these cellars, for it mayn’t have been built up, and we may find it easily enough. Begin then, and let’s try.”

Ben trimmed the candle with his forefinger and thumb, making the flame brighter, and then holding the light close to the flat face of the wall, they examined stone after stone; but as far as they could make out, they had not been tampered with since the day the masons concluded their task.

Then the curved walls right and left were examined quickly, as they were little likely to contain a concealed opening; lastly, the flags on the floor, and, finally, Ben drew his sword and softly tapped each in turn.

But not one gave forth a hollow sound. Everything was solid, even the walls at the back.

“Let’s try the other open one, sir,” said Ben, and they continued their investigations in this place, which was precisely similar to the first, and yielded the same results.

Then the keys of the great bunch Ben carried were tried on one fast-closed door of oak, studded with square nails much corroded by rust, but it was not until the last key had been thrust in that with a harsh creaking the bolt of the ponderous lock shot back; and then it required the united efforts of both to get the door to turn upon the rusty hinges.

Here they were met by precisely the same appearances, and the search was made, and ended by sounding with the sword pommel.

“No, sir; there’s nothing here.”

“I’m afraid not,” said Roy; “everything sounds solid.”

“Ay, sir, and solid it is.”

“But if you tap so hard, Master Pawson will hear you,” whispered Roy, as the old soldier tried the floor again.

“Maybe not, sir; but if he do, he do. Let’s hope now he’s fast asleep; you see, he’s three floors higher up.”

“But knocking sounds travel a long distance, Ben, and I’d rather he did not know.”

“Me too, sir. Well, this is only three. Let’s try the others.”

“I hope you are not going to have so much work with the finding of the key,” said Roy; “it hinders us so.”

“Plenty of time before morning, sir,” replied Ben, coolly; and after relocking the heavy low door, he tried the key he had just withdrawn upon the next door, and, to the surprise of both, it yielded easily, and was thrown open.

Again the same clean, swept-out place, with plenty of grey cobwebs; but that was all.

Upon sounding the stones, however, at the back, they fancied that they detected a suggestion of hollowness, still not enough to make Roy determine to have the wall torn down.

This place was locked and the next tried, the only satisfactory part of the business being that the key before used evidently opened all the locks in the basement of this tower; and so it proved, as one after the other the dungeons or cellars were tried with the same unsatisfactory results, for none of the eight afforded the slightest trace of the clew they sought.

At last, pretty well tired out and covered with cobwebs, they stood in the crypt while Ben lit a fresh candle, the first having burned down into the socket, with the wick swimming in molten fat, and Roy said, with a yawn—

“I wonder whether there is a passage after all, or whether it is some old woman’s tale.”

“Nay, sir, there is,” said the old soldier, solemnly. “Your father said there was, and he must have known.”

“Well, then, where is the door?” said Roy, peevishly.

“Ah! that’s what we’ve got to find out, sir. You’re tired now, and no wonder. So let’s try another night. You’re not going to give a thing up because you didn’t do it the first time.”

“I hope not,” said Roy, with another yawn; “but I am a bit tired now. I say, Ben, though, think it’s in one of the places we’ve filled up with stores?”

“I hope not, sir; that would be making too hard a job of it.”

“Stop a moment,” cried Roy, brightening up; “I have it.”

“You know where it is, sir?” cried Ben, eagerly.

“Not this end,” said Roy, laughing, “but the other.”

“What, in the old ruins? Of course.”

“Well, why not go and find that, and then trace it down to here. It would be the easiest way.”

“There is something in that, sir, certainly,” said the old soldier, thoughtfully; “ever been there, sir?”

“Once, blackberrying; but of course I never saw anything; only a rabbit or two.”

“Then if we can’t find it here after a good try or two, sir, we’ll have a walk over there some evening, though I don’t feel to like the idea of leaving the place, specially as all the gentry seem so unfriendly. Not a soul, you see, has been to see her ladyship. Looks bad, Master Roy, and as if there was more going on than we know of round about us.”

“Ah, well, never mind that,” said Roy; “let’s get back out of this chilly, echoing place. I’m fagged.”

“We’ll go back this way, sir,” said Ben; and he went on first with the lantern, till he came to one of the flights of stone steps leading up to the ground level.

“Let’s go on here, Ben,” said Roy; and, upon their reaching the corridor above, the boy looked back along it towards where the stairs went up into the corner tower, beneath which they had been so busy.

“Wonder whether Master Pawson heard us, Ben.”

“Can’t say, sir. I should fancy not, or he’d have been on the stir to know what was the matter.”

“Mightn’t have cared to stir in the dark, Ben. I say, I should like to know. Look here, he went off early to bed, because he said he was unwell. I’ll go and ask how he is. That’s a good excuse for seeing.”

“Well, so it is, sir,” said Ben, rubbing his ear; “and if he did hear anything, he’d be pretty sure to speak.”

“Of course. Then I will go. Come and light me.” Roy hurried along back with Ben following and casting the boy’s shadow before him, till they reached the arched door-way, where they went up the few stone steps in the spiral staircase, reached the oaken door leading into the apartments, felt for the latch, raised it, and gave it a loud click; but the door did not yield to the boy’s pressure, and he tried it again, and then gave it a shake. “Why, he has locked himself in, Ben!”

“Has he, sir? Didn’t want to be ’sturbed, maybe.”

“Perhaps he was frightened by the noise we made, and then fastened himself in,” said Roy, with a laugh.

Ben chuckled at the idea.

“Well, sir, not the first time we’ve frightened him, eh?”

“Hush! I want to let him know who it is now knocking,” said Roy; “it is startling to be woke up in the middle of the night. Master Pawson—Master Pawson!” he said, gently; and he tapped lightly with his fingers.

But there was no reply, and Roy tapped and called again, but still without result.

“He’s too fast asleep to hear you, sir.”

“Well, he ought to bear that,” said Roy, giving the door a good rattle, and then tapping loudly.

“One would think so, sir; but he don’t seem to have his ears very wide open, or else he’s too much scared to stir.”

“Master Pawson! Master Pawson!” cried Roy, loudly now; and he once more rattled the door. “How are you?”

“Fast as a church, sir,” said Ben; “and I wouldn’t rattle no more, because you’ll be having the sentry up atop after us. Better go and speak to him, or he’ll be raising the guard.”

Ben went up on the winding stair, and spoke to the sentry, who challenged him as he reached the top, and was much relieved on hearing his sergeant’s voice.

“Didn’t know what to make of it,” he said; “and I should have fired, only my piece wouldn’t go off.”

“Well, let this be a lesson to you, my lad, to keep your firelock in order.”

“Yes, sergeant; I will in future.”

“We might have been the enemy coming. See any more of that light, or hear any more noise over yonder?”

“No, nothing.”

“Not heard nothing from Master Pawson, I suppose?”

“Not since he came up and spoke to me before he went to bed. Said his head was queer or something—spoke mighty pleasant, and that he was sorry for me who had to watch all night.”

“Well?”

“That was all; only I said I was sorry for him having such a bad head.”

Ben went down to where Roy was waiting in the secretary’s door-way.

“Can’t wake him, Ben. Come along; I am tired now.”

“Feel as if an hour’s sleep wouldn’t do me much harm, sir,” said the old soldier; and they went on along the corridor, whose windows looked out upon the pleasaunce. “Master Pawson’s in the right of it. Once a man’s well asleep, it’s a woundy, tiresome thing to be wakened up. Good-night, sir.”

“Good-morning, you mean, Ben,” said Roy, laughing.

“Oh, I calls it all night till the sun’s up again, sir. You and me’ll have to try the old ruins, I s’pose, though I don’t expect we shall find anything there.”

Roy went straight to his room, half undressed, and threw himself upon the bed, to begin dreaming directly that he had discovered the entrance to the secret passage at the other end, but it was so blocked up with stones and tree-roots that there was no way in, and would not be until he had persuaded his mother to do away with the garden, cut down the trees, and turn the place back into a regular court-yard such as old Ben wished.