Chapter 44 | The Evasion | Yussuf the Guide

Three months had passed away, and though the hopes of the prisoners had been raised several times by the commencement of a thaw, this had been succeeded again and again by heavy falls of snow, and by repeated frosts which bound them more closely in the stronghold.

But at last the weather completely changed. The wind came one day cloud-laden, and with a peculiar sensation of warmth. Thick mists hid the mountain tops, and filled up the valleys, and a few hours later the professor and his companions had to make a rush for the shelter of the great hall that was their prison, for a terrific downpour commenced, and for the next fortnight continued almost incessantly.

The change that took place was astounding; the mountain sides seemed to be covered with rills, which rapidly grew, as they met, into mountain torrents, which swirled and foamed and cut their way through the dense masses of snow, till they were undermined and fell with loud reports; every now and then the loosened snow high up began to slide, and gathered force till it rushed down as a mighty avalanche, which crashed and thundered on its course, bearing with it rock and tree, and quite scraping bare places that had been covered with forest growth.

At first the prisoners started up in alarm as they heard some terrible rush, but where they were placed was out of danger; and by degrees they grew used to the racing down of avalanche, and the roar of the leaping and bounding torrents, and sat talking to Yussuf all through that wet and comfortless time about the probabilities of their soon being able to escape.

“The snow is going fast,” he said; “but for many days the mountain tracks will be impassable. We must wait till the torrents have subsided: we can do nothing till then.”

Nearly four months had passed, since they had met the brigands first, before Yussuf announced that he thought they might venture to make a new attempt. The snow had pretty well gone, and the guards were returning to their stations at the great gate. There was an unwonted hum in the settlement, and when the chief came he seemed to take more interest in his prisoners, as if they were so many fat creatures which he had been keeping for sale, and the time had nearly come for him to realise them, and take the money.

In fact, one day Yussuf came in hastily to announce a piece of news that he had heard.

The messengers were expected now at any moment, for a band of the brigands had been out on a long foraging excursion, and had returned with the news that the passes were once more practicable, for the snow had nearly gone, save in the hollows, and the torrents had sunk pretty nearly to their usual state.

“Then we must be going,” said Mr Burne, “eh?”

“Yes, effendi,” said the guide, “before they place guards again at our door. We have plenty of provisions saved up, and we will make the attempt to-night.”

This announcement sent a thrill through the little party, and for the rest of the day everyone was pale with excitement, and walked or sat about waiting eagerly for the coming of night.

There was no packing to do, except the tying up of the food in the roughly-made bags they had prepared, and the rolling up of the professor’s drawings—for they had increased in number, the brigand chief having, half-contemptuously, given up the paper that had been packed upon the baggage-horses.

Mr Preston was for making this into a square parcel, but Yussuf suggested the rolling up with waste paper at the bottom, and did this so tightly that the professor’s treasure, when bound with twine, assumed the form of a stout staff—“ready,” Mr Burne said with a chuckle, “for outward application to the head as well as inward.”

All through the rest of that day the motions of the people were watched with the greatest of anxiety, and a dozen times over the appearance of one of the brigands was enough to suggest that suspicion had been aroused, and that they were to be more closely watched.

But the night came at last—a dark still night without a breath of air; and as, about six o’clock as near as they could guess, everything seemed quiet, Yussuf went out and returned directly to say that there were no guards placed, and that under these circumstances it would be better to go at once. No one was likely to come again, so they might as well save a few hours and get a longer start.

This premature announcement startled Mrs Chumley, so that she turned faint with excitement, and unfortunately the only thing they could offer her as a restorative was some grape treacle.

This stuff Chumley insisted upon her taking, and the annoyance roused her into making an effort, and she rose to her feet.

“I’m ready,” she said shortly; and then in a whisper to her husband, “Oh, Charley, I’ll talk to you for this.”

“Silence!” whispered Yussuf sternly. “Are you all ready?”

“Yes.”

“Then follow as before, and without a word.”

He drew aside the rug, and the darkness was so intense that they could not see the nearest building as they stepped out; but, to the horror of all, they had hardly set off when a couple of lanterns shone out. A party of half a dozen men, whose long gun-barrels glistened in the light, came round one of the ruined buildings, and one of them, whose voice sent a shudder through all, was talking loudly.

The voice was that of the chief, and as the fugitives crouched down, Yussuf heard him bid his men keep a very stringent look-out, for the prisoners might make an attempt to escape.

Yussuf caught Lawrence’s hand and drew him gently on, while, as he had Mrs Chumley’s tightly grasped, she naturally followed, and the others came after.

“Quick!” whispered Yussuf, “or we shall be too late.”

The darkness was terrible, but it was in their favour, so long as they could find the way to the old temple; and they needed its protection, for they had not gone many yards among the ruins before there was an outcry from the prison, then a keen and piercing whistle twice repeated, and the sounds of hurrying feet.

Fortunately the old temple lay away from the inhabited portion: and as they hurried on, to the great joy of all they found that the chief and his men  were not upon their track, but were hurrying toward the great rock gates, thus proving at once, so it seemed, that they were ignorant of any other way out of the great rock-fortress.

were not upon their track, but were hurrying toward the great rock gates, thus proving at once, so it seemed, that they were ignorant of any other way out of the great rock-fortress.

Once or twice Yussuf was puzzled in the darkness, but he caught up the trail again, and in a few minutes led them to the columned entrance of the temple, into whose shelter they passed with the noise and turmoil increasing, and lights flashing in all directions.

“Hadn’t we better give up,” said Mr Chumley, with his teeth chattering from cold or dread.

“Give up! What for?” cried Mr Burne.

“They may shoot us,” whispered the little man. “I don’t mind, but—my wife.”

“Silence!” whispered Yussuf, for the noise seemed to increase, and it was evident that the people were spreading all over the place in the search.

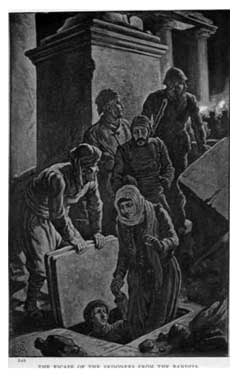

As Yussuf spoke he hurried them on, and in a minute or two reached the stone that led to the passage in the rift.

It was quite time he did, for some of the people, who knew how they had affected that place, were making for the temple.

But Yussuf lost no time. He turned up the stone in an instant, and stood holding it ready.

“Go first, Lawrence effendi,” he whispered; “help Lady Chumley and lead the way.”

Lawrence dropped down at once, and Mrs Chumley followed with unexpected agility; then Chumley, Mr Burne, the professor; and as Yussuf was following, lights flashed through the old building, and lit up the roof.

Fortunately the ruins of the ancient altar sheltered the guide, as he stepped down and carefully lowered the stone over his head as he descended; and so near was he to being seen that, as the stone sank exactly into its place, a man ran over it, followed by half a dozen more, their footsteps sounding hollow over the fugitives’ heads.

Meanwhile Lawrence hurried Mrs Chumley down, the others following closely, till the bottom of the steps and slopes was reached, and the cool night air came softly in through the opening.

There they stopped for Yussuf to act as guide; but, though his name was repeated in the darkness again and again, there was no answer, and it soon became evident that he was not with the party.

“We cannot go without him,” said Mr Preston sternly. “Stop here, all of you, and I will go back and try to find him.” But there was no need, for just then they heard him descending.

“I stopped to listen,” he said. “They have not yet found our track, and perhaps they may not; but they are searching the temple all over, for they have found something, and I don’t know what.”

“My bag of bread and curd!” said Mr Chumley suddenly. “I dropped it near the door.”

“Hah!” ejaculated Yussuf; but no one else said a word, though they thought a great deal, while Mr Chumley uttered a low cry in the darkness, such a cry as a man might give who was suffering from a sharp pinch given by his wife.

The next moment the guide passed them, and they heard him thrust out a stone, which went rushing down the precipice, and fell after some moments, as if at a great distance, with a low pat. Then Yussuf bade them follow, and one by one they passed out on to a narrow rocky shelf, to stand listening to the buzz of voices and shouting far above their heads, where a faint flickering light seemed to be playing, while they were in total darkness.

“Be firm and there is no danger,” said Yussuf; “only follow me closely, and think that I am leading you along a safe road.”

The darkness was, on the whole, favourable, for it stayed the fugitives from seeing the perilous nature of the narrow shelf, where a false step would have plunged them into the ravine below; but they followed steadily enough, with the way gradually descending. Sometimes they had to climb cautiously over the rocks which encumbered the path, while twice over a large stone blocked their way, one which took all Yussuf’s strength to thrust it from the narrow path, when it thundered into the gorge with a noise that was awful in the extreme.

Then on and on they went in the darkness, and almost in silence, hour after hour, and necessarily at a very slow pace. But there was this encouragement, that the lights and sounds of the rock-fortress gradually died out upon vision and ear, and after turning a sharp corner of the rocks they were heard no more.

“I begin to be hopeful that they have not found out our way of escape,” said Mr Preston at last in a cheerful tone; but no one spoke, and the depressing walk was continued, hour after hour, with Yussuf untiringly leading the way, and ever watchful of perils.

From time to time he uttered a few words of warning, and planted himself at some awkward spot to give a hand to all in turn before resuming his place in front.

More than once there was a disposition to cry halt and rest, for the walk in the darkness was most exhausting; but the danger of being captured urged all to their utmost endeavours, and it was not till daybreak, which was late at that season of the year, that Yussuf called a halt in a pine-wood in a dip in the mountains, where the pine needles lay thick and dry; and now, for the first time, as the little party gazed back along the faint track by which they had come through the night, they thoroughly realised the terrible nature of their road.

“Everyone lie down and eat,” said Yussuf in a low voice of command. “Before long we must start again.”

He set the example, one which was eagerly followed, and soon after, in spite of the peril of their position and the likelihood of being followed and captured by the enraged chief, everyone fell fast asleep, and felt as if his or her eyes had scarcely been closed when, with the sun shining brightly, Yussuf roused them to continue their journey.

The path now seemed so awful in places, as it ran along by the perpendicular walls of rock, that Chumley and Lawrence both hesitated, till the latter saw Yussuf’s calm smile, full of encouragement, when the lad stepped out firmly, and seeing that his wife followed, the little man drew a long breath and walked on.

Now they came to mountain torrents that had to be crossed; now they had to go to the bottom of some deep gorge; now to ascend; but their course was always downwards in the aggregate, and at nightfall, when Yussuf selected another pine-wood for their resting-place, the air was perceptibly warmer.

The next morning they continued along the faintly marked track, which was kept plain by the passage of wild animals; but it disappeared after descending to a stream in a defile; and this seemed to be its limit, for no trace of it was seen again.

For six days longer the little party wandered in the mazes of these mountains, their guide owning that he was completely at fault, but urging, as he always led them down into valleys leading to the south and west, that they must be getting farther away from danger.

It was this thought which buoyed them up during that nightmare-like walk, during which they seemed to be staggering on in their sleep and getting no farther.

It seemed wonderful that they should journey so far, through a country that grew more and more fertile as they descended from the mountains, without coming upon a village or town; but, though they passed the remains of three ancient places, which the professor was too weary to examine, it was not until the seventh day that they reached a goodly-sized village, whose head-man proved to be hospitable, and, on finding the state to which the travellers had been reduced and the perils through which they had passed, he made no difficulty about sending a mounted messenger to Ansina, ninety miles away, with letters asking for help.