Chapter 33 | An Exchange | Blue Jackets

“Now then,” said Mr Brooke, after a few minutes’ pause, “what’s the first thing, Herrick? We can’t keep watch for the junks in this boat.”

“The first thing is to get her mended, sir.”

“Yes; but how?”

“Let’s ask Ching.”

“Ching!” said Mr Brooke angrily.

“You wantee Ching?” came in the familiar highly-pitched voice from forward. “You wantee Ching go buy new boatee?”

He came hurrying aft, nearly tumbling once; while, left to his own power alone, the coxswain redoubled his efforts to keep down the water, and the tin baler went scoop scroop, scoop scroop, and splash splash, as he sent the water flying.

But the dark, angry expression of Mr Brooke’s countenance repelled the Chinaman, and he stopped short and looked from one to the other in a pleading, deprecating way, ending by saying piteously—

“You no wantee Ching?”

Mr Brooke shook his head, and our interpreter went back over the thwarts, reseated himself, and began to bale again, with his head bent down very low.

“Give way, my lads,” said Mr Brooke, bearing hard on the tiller, and the boat began to bear round as he steered for the landing-place a quarter of a mile away.

I looked up at him inquiringly, and he nodded at me.

“We can’t help it, Herrick,” he said; “if we stop afloat with the boat in this condition we shall have a serious accident. But we shall lose the junks.”

“Oh!” I ejaculated, “and after all this trouble. We had been so successful too. Couldn’t we repair the boat?”

“If we could run into a good boat-builder’s we might patch it up, but we can do nothing here.”

“Couldn’t Ching show us a place?”

“I can’t ask the scoundrel.”

I winced, for I could not feel that Ching had deceived us, and for a few moments I was silent. Then a thought struck me.

“May I ask him, sir?”

Mr Brooke was silent for a while, but he spoke at last.

“I hate risking his help again, but I am ready to do anything to try and carry out my instructions. We ought to patrol the river here to wait for the junks coming down, and then follow them, even if it is right down to sea. Well, yes; ask him it he can take us to a boat-builder’s, where we can get some tarpaulin or lead nailed on.”

I wasted no time. “Ching!” I cried; and he looked up sadly, but his face brightened directly as he read mine.

“You wantee Ching?”

“Yes; where is there a boat-builder’s where they will mend the boat directly?”

“No,” he said; “takee velly long time. Boat-builder same slow fellow. No piecee work along. Take boatee out water, mend him to-mollow, next week.”

“Then what are we to do?” I cried. “We want to watch the junks.”

“Why no takee other fellow big boatee? Plenty big boatee evelywhere. Get in big sampan junk, pilate man no sabby jolly sailor boy come along. Think other piecee fellow go catch fish.”

“Here, Mr Brooke,” I cried excitedly; “Ching says we had better take one of these boats lying moored out here, and the pirates won’t think of it being us. Isn’t it capital?”

Mr Brooke gazed sharply at us both for a few moments, and then directed the boat’s head as if going up the river again.

“Where is there a suitable boat?” he said hoarsely, and speaking evidently under great excitement, as he saw a means of saving the chance after all.

“Velly nice big boat over ’long there,” said Ching, pointing to a native craft about double the size of our cutter, lying moored about a hundred yards from the shore, and evidently without any one in her.

“Yes, that will do,” cried Mr Brooke. “Anything fits a man who has no clothes. Pull, my lads—give way!”

The men dragged at the oars, and I saw that since Ching had left off baling the water was gaining fast, and that if more power was not put on it would not be long before the boat was waterlogged or sunk.

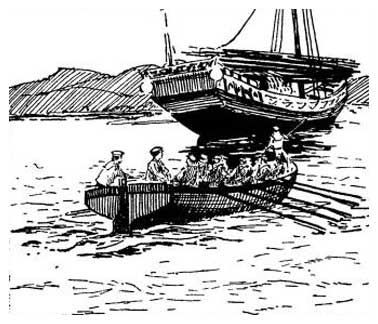

In a minute we were alongside the boat, one of a superior class, possibly belonging to some man of consequence, and Mr Brooke had run the cutter along her on the side farthest from the shore, so that our proceedings were not noticed, as we made fast.

“Now then, tumble in, my lads,” he cried; “take the oars and everything movable. Throw them in, our game and all. Here, Herrick, take both guns.”

Everything was transferred in a very short time; and this done, Mr Brooke stepped aboard the little junk-like craft, gave his orders, and a line was attached to a grating, the other end to one of the ring-bolts. Then the craft’s anchor-line was unfastened, and our painter hitched on to it instead. Next the grating was tossed overboard, with plenty of line to float it as a buoy and show where the boat had sunk, as it was pretty certain to do before long; and we, in our tiny junk, began to glide away with the tide, furnished with a serviceable boat, boasting of sails, even if they were not of a kind our men were accustomed to manage.

“Why, it is grand, Herrick!” cried Mr Brooke excitedly. “We shall get them after all.”

“And all Ching’s doing, sir,” I said quietly.

“Ah, yes, perhaps; he is repentant now he has been found out. But we shall see—”

“That he is quite innocent, sir,” I said.

“I hope so, my lad. Now, let’s make sail, and beat about here, to and fro. We must keep a good watch for our two friends, and if they come down we can follow till we see the Teaser in the offing. We may, I say, capture them yet.”

A sail was hoisted, and in a few minutes we found that the  craft went along easily and well, answering to her helm admirably. Her high bulwarks gave plenty of shelter, and would, I saw, well conceal our men, so that we had only to put Ching prominently in sight to pass unnoticed, or as a Chinese fishing or pleasure boat.

craft went along easily and well, answering to her helm admirably. Her high bulwarks gave plenty of shelter, and would, I saw, well conceal our men, so that we had only to put Ching prominently in sight to pass unnoticed, or as a Chinese fishing or pleasure boat.

Just then I turned and found him close behind me, rubbing his hands.

“You ask Mr Blooke he likee Ching sit where pilate see him ’gain?” he said.

“I am sure he would,” I replied.

He looked sad again directly, and just touched the sleeve of my Norfolk jacket with the long nail of his forefinger.

“Ching velly solly,” he said.

“What about?”

“Mr Blooke think Ching fliends with pilates. Velly shocking; Ching hate pilates dleadfully; hollid men.”

“Yes, I am sure you do,” I said.

The Celestial’s face lit up again directly, and he rubbed his hands.

“Ching velly—”

“Yes?” I said, for Mr Brooke called to me from the little cabin contrived for shelter in the after part of the vessel.

“Look here,” he said, as I joined him, “we can keep below here, and command the river too, without being seen. Why, Herrick, my lad, this is capital; they will never suspect this Chinese boat to be manned by a crew of Her Majesty’s Jacks.”

“Then everything has turned out for the best,” I cried eagerly.

“Humph! that remains to be proved, my lad. We’ve got to return and face Mr Reardon and the captain, and the first question asked of an officer who has been entrusted with one of Her Majesty’s boats, and who returns without it, is— What have you done with the boat or ship? We—yes, you are in the mess, sir—have to go back and say that we have lost it.”

“Why, the captain owned to Pat that a thing couldn’t be lost when you knew where it was.”

“I don’t understand you, my lad,” said Mr Brooke.

“Don’t you remember about the captain’s tea-kettle, sir, that Pat dropped overboard? It was not lost, because Pat knew where it was—at the bottom of the sea.”

“Oh yes, I remember; but I’m afraid Captain Thwaites will not take that excuse.”

“Why, she has gone down already, sir,” I said, as I looked over the side for the boat we had left.

“Yes; but I can see the grating floating. The coxswain took his jacket out of the hole.”

He pointed to the stout piece of woodwork which we had turned into a buoy, but I could not make it out, and I thought it did not much matter, for something else had begun to trouble me a great deal just then, and I waited very anxiously for my officer to make some proposal.

But it did not come at once, for Mr Brooke was planning about the watch setting, so as to guard against the junks coming down the river and passing us on their way out to sea.

But at last all was to his satisfaction, one man keeping a look-out up the river for the descending junks, the other downward to the mouth for the return of the Teaser, whose coming was longed for most intensely.

Then, with just a scrap of sail raised, the rest acting as a screen dividing the boat, we tacked about the river, keeping as near as was convenient to the spot where the Teaser had anchored, and at last Mr Brooke said to me, just in the grey of the evening—

“I’m afraid the lads must be getting hungry.”

“I know one who is, sir,” I said, laughing.

He smiled.

“Well, I have been too busy and anxious to think about eating and drinking,” he said; “but I suppose I am very hungry too. Here, my lad, pass that basket along, and serve out the provisions.”

“You likee Ching serve out plovisions?”

Mr Brooke frowned, and the Chinaman shrank away. I noticed too that when the food was served round, the men took each a good lump of salt pork and a couple of biscuits, Ching contented himself with one biscuit, which he took right forward, and there sat, munching slowly, till it was dark and the shore was lit up with thousands of lanterns swinging in shop, house, and on the river boats moored close along by the shore.

“Bad for us,” said Mr Brooke, as we sat together astern steering, and keeping a sharp look ahead for the expected enemy.

“Why?” I asked.

“Getting so dark, my lad. We shall be having the junks pass us.”

“Oh no, sir. Ching is keen-sighted, and all the men are looking out very eagerly.”

“Ah, well, I hope they will not slip by. They must not, Herrick. There is one advantage in this darkness, though: they will not find us out.”

The darkness favouring the movement, and so as to save time, ready for any sudden emergency, he ordered the men to buckle on their cutlass-belts and pouches, while the rifles were hid handy.

“In case we want to board, Herrick.”

“Then you mean to board if there is a chance?” I said.

“I mean to stop one of those junks from putting to sea, if I can,” he replied quietly. “The Teaser having left us, alters our position completely. She has gone off on a false scent, I’m afraid, and we must not lose the substance while they are hunting the shadow.”

Very little more was said, and as I sat in the darkness I had plenty to think about and picture out, as in imagination I saw our queer-looking boat hooked on to the side of a great high-pooped junk, and Mr Brooke leading the men up the side to the attack upon the fierce desperadoes who would be several times our number.

“I don’t know what we should do,” I remember thinking to myself, “if these people hadn’t a wholesome fear of our lads.”

Then I watched the shore, with its lights looking soft and mellow against the black velvety darkness. Now and then the booming of gongs floated off to us, and the squeaking of a curious kind of pipe; while from the boats close in shore the twangling, twingling sound of the native guitars was very plain—from one in particular, where there was evidently some kind of entertainment, it being lit up with a number of lanterns of grotesque shapes. In addition to the noise—I can’t call it music—of the stringed instruments, there came floating to us quite a chorus of singing. Well, I suppose it was meant for singing; but our lads evidently differed, for I heard one man say in a gruff whisper—

“See that there boat, messmate?”

“Ay,” said another. “I hear it and see it too.”

“Know what’s going on?”

“Yes; it’s a floating poulterer’s shop.”

“A what?”

“A floating poulterer’s shop. Can’t you hear ’em killing the cats?”

This interested me, and I listened intently.

“Killing the cats?” said another.

“Ay, poor beggars. Lor’ a mussy! our cats at home don’t know what horrible things is done in foreign lands. They’re killing cats for market to-morrer, for roast and biled.”

“Get out, and don’t make higgerant observations, messmate. It’s a funeral, and that’s the way these here heathens show how sorry they are.”

“Silence there, my lads,” said the lieutenant. “Keep a sharp look-out.”

“Ay, ay, sir.”

Just at that moment, as the lit-up boat glided along about a couple of hundred yards from us, where we sailed gently up-stream, there was a faint rustling forward, and Tom Jecks’ gruff voice whispered—

“What is it, messmate?”

“Ching see big junk.”

There was a dead silence, and we all strained our eyes to gaze up-stream.

“Can’t see nought, messmate,” was whispered.

“Yes; big junk come along.”

Plash! and a creaking, rattling sound came forth out of the darkness.

“It is a big junk,” said Mr Brooke, with his lips to my ear; “and she has anchored.”

Then from some distance up the river we saw a very dim lantern sway here and there, some hoarse commands were given, followed by the creaking and groaning of a bamboo yard being lowered, and then all was perfectly still.

What strange work it seemed to be out there in the darkness of that foreign river, surrounded by curious sights and sounds, and not knowing but what the next minute we might be engaged in deadly strife with a gang of desperadoes who were perfectly indifferent to human life, and who, could they get the better of us, would feel delight in slaughtering one and all. It was impossible to help feeling a peculiar creepy sensation, and a cold shiver ran through one from time to time.

So painful was this silence, that I felt glad when we had sailed up abreast of the great vessel which had dropped anchor in mid-stream, for the inaction was terrible.

We sailed right by, went up some little distance, turned and came back on the other side, so near this time that we could dimly make out the heavy masts, the huge, clumsy poop and awkward bows of the vessel lying head to stream.

Then we were by her, and as soon as we were some little distance below Mr Brooke spoke—

“Well, my lads, what do you say: is she one of the junks?”

“No pilate junk,” said Ching decisively, and I saw Mr Brooke make an angry gesture—quite a start.

“What do you say, my lads?”

“Well, sir, we all seem to think as the Chinee does—as it arn’t one of them.”

“Why?”

“Looks biggerer and clumsier, and deeper in the water.”

“Yes; tlade boat from Hopoa,” said Ching softly, as if speaking to himself.

“I’m not satisfied,” said Mr Brooke. “Go forward, Mr Herrick; your eyes are sharp. We’ll sail round her again. All of you have a good look at her rigging.”

“Ay, ay, sir,” whispered the men; and I crept forward among them to where Ching had stationed himself, and once more we began gliding up before the wind, which was sufficiently brisk to enable us to easily master the swift tide.

As I leaned over the side, Ching heaved a deep sigh.

“What’s the matter?” I whispered.

“Ching so velly mislable,” he whispered back. “Mr Blooke think him velly bad man. Think Ching want to give evelybody to pilate man. Ching velly velly solly.”

“Hist! look out!”

I suppose our whispering had been heard, for just as we were being steered pretty close to the anchored junk, a deep rough voice hailed us something after this fashion, which is as near as I can get to the original—

“Ho hang wong hork ang ang ha?”

“Ning toe ing nipy wong ony ing!” cried Ching.

“Oh ony ha, how how che oh gu,” came from the junk again, and then we were right on ahead.

“Well,” whispered Mr Brooke, “what does he say? Is it one of the pirate vessels?”

“No pilate. Big boat come down hong, sir. Capin fellow want to know if we pilate come chop off head, and say he velly glad we all good man.”

“Are you quite sure?” said Mr Brooke.

I heard Ching give a little laugh.

“If pilate,” he said, “all be full bad men. Lightee lantern; thlow stink-pot; make noise.”

“Yes,” said Mr Brooke; “this cannot be one of them. Here, hail the man again, and ask him where he is going.”

“How pang pong won toe me?” cried Ching, and for answer there came two or three grunts.

“Yes; what does he say?”

“Say he go have big long sleep, ’cause he velly tired.”

Mr Brooke said no more, but ran the boat down the river some little distance and then began to tack up again, running across from side to side, so as to make sure that the junks did not slip by us in the darkness. But hour after hour glided on, and the lights ashore and on the boats gradually died out, till, with the exception of a few lanterns on vessels at anchor, river and shore were all alike one great expanse of darkness, while we had to go as slowly as possible, literally creeping along, to avoid running into craft moored in the stream.

And all this time perfect silence had to be kept, and but for the intense desire to give good account of the junks, the men would soon have been fast asleep.

“Do you think they will come down and try to put to sea, Ching?” I said at last, very wearily.

“Yes, allee ’flaid Queen Victolia’s jolly sailor boy come steam up liver and send boat up cleek, fight and burn junks. Come down velly quick.”

“Doesn’t seem like it,” I said, beginning at last to feel so drowsy I could not keep my eyes open.

“So velly dark, can’t see.”

“Why, you don’t think they will get by us in the darkness?” I said, waking up now with a start at his words, and the bad news they conveyed.

“Ching can’t tell. So velly dark, plenty junk go by; nobody see if velly quiet. Ching hope not get away. Wantee Mr Brooke catchee both junk, and no think Ching like pilate man.”

“Here, I must go and have a talk to Mr Brooke,” I said; and I crept back to where he sat steering and sweeping the darkness he could not penetrate on either side.

“Well, Herrick,” he said eagerly. “News?”

“Yes, sir; bad news. Ching is afraid that the junks have crept by us in the night.”

“I have been afraid so for some time, my lad, for the tide must have brought them down long enough ago.”

He relapsed into silence for a few minutes, and then said quietly—

“You can all take a sleep, my lads; Mr Herrick and I will keep watch.”

“Thankye, sir, thankye,” came in a low murmur, and I went forward to keep a look-out there; but not a man lay down, they all crouched together, chewing their tobacco, waiting; while Ching knelt by the bows, his elbows on the gunwale, his chin resting upon his hands, apparently gazing up the river, but so still that I felt he must be asleep, and at last startled him by asking the question whether he was.

“No; too much head busy go sleep. Want findee allee pilate, show Mr Blooke no like pilate. Velly ’flaid all gone.”

How the rest of that night went by, I can hardly tell. We seemed to be for hours and hours without end tacking to and fro, now going up the river two or three miles, then dropping down with the tide, and always zig-zagging so as to cover as much ground as possible. The night lengthened as if it would never end; but, like all tedious times of the kind, it dragged its weary course by, till, to my utter astonishment, when it did come, a faint light dawned away over the sea beyond the mouth of the river, just when we were about a mile below the city.

That pale light gradually broadened, and shed its ghastly chilly beams over the sea, making all look unreal and depressing, and showed the faces of our crew, sitting crouched in the bottom of the boat, silent but quite wide-awake.

Then all started as if suddenly electrified, for Ching uttered a low cry, and stood up, pointing right away east.

“What is it?” I said.

“Two pilate junk.”

We all saw them at the same time, and with a miserable feeling of despondency, for there was no hiding the fact. The river was wide, and while we were close under one bank they had glided silently down under the other, and were far beyond our reach.