Chapter 37 | Jack Ashore | Blue Jackets

All was quiet on the junks, not a man being visible as we sailed out of the river and along the south shore of the estuary; and now, after a long examination, Mr Brooke declared that there couldn’t be a doubt as to their being the ones we had seen up the branch river when we were in the trap.

“The rig is too heavy for ordinary traders, Herrick,” he said; and he pointed out several peculiarities which I should not have noticed.

Ching had been watching us attentively, and Mr Brooke, who evidently wanted to make up now for his harsh treatment of the interpreter, turned to him quietly—

“Well, what do you say about it, Ching?”

The interpreter smiled.

“Ching quite su’e,” he replied. “Seen velly many pilate come into liver by fancee shop. Ching know d’leckly. Velly big mast, velly big sail, go so velly fast catchee allee ship. You go waitee all dalk, burn all up.”

“What! set fire to them?”

“Yes; velly easy. All asleep, no keepee watch like Queen ship. No light. Cleep velly close up top side, big wind blow; make lit’ fire both junk and come away. Allee ’light velly soon, and make big burn.”

“What! and roast the wretches on board to death?”

“Some,” said Ching, with a pleasant smile. “Makee squeak, and cly ‘Oh! oh!’ and burn all ’way like fi’wo’k. Look velly nice when it dalk.”

“How horrid!” I cried.

“Not all bu’n up,” said Ching; “lot jump ove’board and be dlown.”

“Ching, you’re a cruel wretch,” I cried, as Mr Brooke looked at the man in utter disgust.

“No; Ching velly glad see pilate bu’n up and dlown. Dleadful bad man, bu’n ship junk, chop off head. Kill hundleds poo’ good nicee people. Pilate velly hollid man. Don’t want pilate at all.”

“No, we don’t want them at all,” said Mr Brooke, who seemed to be studying the Chinaman’s utter indifference to the destruction of human life; “there’s no room for them in the world, but that’s not our way of doing business. Do you understand what I mean?”

“Yes, Ching understand, know. Ching can’t talk velly quick Inglis, but hear evelyting.”

“That’s right. Well, my good fellow, that wouldn’t be English. We kill men in fair fight, or take them prisoners. We couldn’t go and burn the wretches up like that.”

Ching shook his head.

“All velly funnee,” he said. “Shoot big gun and make big hole in junk; knockee all man into bit; makee big junk sink and allee men dlown.”

“Yes,” said Mr Brooke, wrinkling up his forehead.

“Why not make lit’ fire and bu’n junk, killee allee same?”

“He has me there, Herrick,” said Mr Brooke.

“Takee plisoner to mandalin. Mandalin man put on heavy chain, kick flow in boat, put in plison, no give to eat, and then choppee off allee head. Makee hurt gleat deal mo’. Velly solly for plisoner. Bette’ make big fi’ and bu’n allee now.”

Mr Brooke smiled and looked at me, and I laughed.

“We’d better change the subject, Herrick,” he said. “I’m afraid there is not much difference in the cruelty of the act.”

“No, sir,” I said, giving one of my ears a rub. “But it is puzzling.”

“Yes, my lad; and I suppose we should have no hesitation in shelling and burning a pirates’ nest.”

“But we couldn’t steal up and set fire to their junks in the dark, sir?”

“No, my lad, that wouldn’t be ordinary warfare. Well, we had better run into one of these little creeks, and land,” he continued, as he turned to inspect the low, swampy shore. “Plenty of hiding-places there, where we can lie and watch the junks, and wait for the Teaser to show.”

“Velly good place,” said Ching, pointing to where there was a patch of low, scrubby woodland, on either side of which stretched out what seemed to be rice fields, extending to the hills which backed the plain. “Plenty wood makee fire—loast goose.”

I saw a knowing look run round from man to man.

“But the pirates would see our fire,” I said.

“Yes, see fi’; tink allee fish man catch cookee fish.”

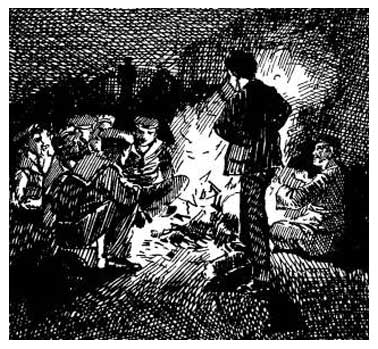

“Yes, you’re right, Ching. It will help to disarm any doubts. They will never think the Teaser’s men are ashore lighting a fire;” and, altering our course a little, he ran the boat in shore and up a creek, where we landed, made fast the boat under some low scrubby trees, and in a very short time after a couple of men were placed where they could watch the junks and give notice of any movement. The others quickly collected a quantity of drift-wood, and made a good fire, Ching tucking up his sleeves and superintending, while Mr Brooke and I went out on the other side of the little wood, and satisfied ourselves that there was no sign of human habitation on this side of the river, the city lying far away on the other.

When we came back, Ching was up to the elbows in shore mud, and we found by him a couple of our geese and a couple of ducks turned into dirt-puddings. In other words, he had cut off their heads, necks, and feet, and then cased them thickly with the soft, unctuous clay from the foot of the bank; and directly we came he raked away some of the burning embers, placed the clay lumps on the earth, and raked back all the glowing ashes before piling more wood over the hissing masses.

“Velly soon cook nicee,” he said, smiling; and then he went to the waterside to get rid of the clay with which he was besmirched.

Mr Brooke walked to the sentinels, and for want of something else to do I stood pitching pieces of drift-wood on to the fire, for the most part shattered fragments of bamboo, many of extraordinary thickness, and all of which blazed readily and sent out a great heat.

“Makes a bit of a change, Mr Herrick, sir,” said Jecks, as the men off duty lay about smoking their pipes, and watching the fire with eyes full of expectation.

“Yes; rather different to being on shipboard, Jecks,” I said.

“Ay, ’tis, sir. More room to stretch your legs, and no fear o’ hitting your head agin a beam or your elber agin a bulkhead. Puts me in mind o’ going a-gipsying a long time ago.”

“‘In the days when we went gipsying, a long time ago,’” chorussed the others musically.

“Steady there,” I said. “Silence.”

“Beg pardon, sir,” said one of the men; and Tom Jecks chuckled. “But it do, sir,” he said. “I once had a night on one o’ the Suffolk heaths with the gipsies; I was a boy then, and we had hare for supper—two hares, and they was cooked just like that, made into clay balls without skinning on ’em first.”

“But I thought they always skinned hares,” I said, “because the fur was useful.”

“So it is, sir; but there was gamekeepers in that neighbourhood, and if they’d found the gipsies with those skins, they’d have asked ’em where the hares come from, and that might have been unpleasant.”

“Poached, eh?”

“I didn’t ask no questions, sir. And when the hares was done, they rolled the red-hot clay out, gave it a tap, and it cracked from end to end, an’ come off like a shell with the skin on it, and leaving the hares all smoking hot. I never ate anything so good before in my life.”

“Yah! These here geese ’ll be a sight better, Tommy,” said one of the men. “I want to see ’em done.”

“And all I’m skeart about,” said another, “is that the Teaser ’ll come back ’fore we’ve picked the bones.”

I walked slowly away to join Mr Brooke, for the men’s words set me thinking about the gunboat, and the way in which she had sailed and left us among these people. But I felt that there must have been good cause for it, or Captain Thwaites would never have gone off so suddenly.

“Gone in chase of some of the scoundrels,” I thought; and then I began to think about Mr Reardon and Barkins and Smith. “Poor old Tanner,” I said to myself, “he wouldn’t have been so disagreeable if it had not been for old Smith. Tanner felt ashamed of it all the time. But what a game for them to be plotting to get me into difficulties, and then find that I was picked out for this expedition! I wish they were both here.”

For I felt no animosity about Smith, and as for Tanner I should have felt delighted to have him there to join our picnic dinner.

I suppose I had a bad temper, but it never lasted long, and after a quarrel at school it was all over in five minutes, and almost forgotten.

I was so deep in thought that I came suddenly upon Mr Brooke, seated near where the men were keeping their look-out. He was carefully scanning the horizon, but looked up at me as I stopped short after nearly kicking against him.

“Any sign of the Teaser sir?” I said.

“No, Herrick. I’ve been trying very hard to make her out, but there is no smoke anywhere.”

“Oh, she’ll come, sir, if we wait. What about the junks?”

“I haven’t seen a man stirring oh board either of them, and they are so quiet that I can’t quite make them out.”

“Couldn’t we steal off after dark, sir, and board one of them? If we took them quite by surprise we might do it.”

“I am going to try, Herrick,” he said quietly, “some time after dark. But that only means taking one, the other would escape in the alarm.”

“Or attack us, sir.”

“Very possibly; but we should have to chance that.” He did not say any more, but sat there scanning the far-spreading sea, dotted with the sails of fishing-boats and small junks. But he had given me plenty to think about, for I was growing learned now in the risks of the warfare we were carrying on, and I could not help wondering what effect it would have upon the men’s appetites if they were told of the perilous enterprise in which they would probably be called upon to engage that night.

My musings were interrupted by a rustling sound behind me, and, turning sharply, it was to encounter the smooth, smiling countenance of Ching, who came up looking from one to the other as if asking permission to join us.

“Well,” said Mr Brooke quietly, “is dinner ready?”

Ching shook his head, and then said sharply—

“Been thinking ’bout junks, they stop there long time.”

“Yes; what for? Are they waiting for men?”

“P’laps; but Ching think they know ’bout other big junk. Some fliends tell them in the big city. Say to them, big junk load with silk, tea, dollar. Go sail soon. You go wait for junk till she come out. Then you go ’longside, killee evelybody, and take silk, tea, dollar; give me lit’ big bit for tellee.”

“Yes, that’s very likely to be the reason they are waiting.”

“Soon know; see big junk come down liver, and pilates go after long way, then go killee evelybody. Muchee better go set fire both junk to-night.”

“We shall see,” said Mr Brooke quietly.

He rose and walked down to the two sentinels.

“Keep a sharp look-out, my lads, for any junks which come down the river, as well as for any movements on board those two at anchor. I shall send and relieve you when two men have had their dinner.”

“Thankye, sir,” was the reply; and we walked back, followed by Ching.

“That last seems a very likely plan, Herrick,” said Mr Brooke. “The scoundrels play into each other’s hands; and I daresay, if the truth was known, some of these merchants sell cargoes to traders, and then give notice to the pirates, who plunder the vessels and then sell the stuff again to the merchants at a cheap rate. But there, we must eat, my lad, and our breakfast was very late and very light. We will make a good meal, and then see what the darkness brings forth.”

We found the men carefully attending to the fire, which was now one bright glow of embers; and very soon Ching announced that dinner was cooked, proceeding directly after to hook out the hard masses of clay, which he rolled over to get rid of the powdery ash, and, after letting them cool a little, he duly cracked them, and a gush of deliciously-scented steam saluted our nostrils.

But I have so much to tell that I will not dwell upon our banquet. Let it suffice that I say every one was more than satisfied; and when the meal was over, Ching set to work again coating the rest of our game with clay, and placed them in the embers to cook.

“Velly good, velly nicee to-day,” he said; “but sun velly hot, night velly hot, big fly come to-mollow, goose not loast, begin to ’mell velly nasty.”

As darkness fell, the fire was smothered out with sand, there being plenty of heat to finish the cookery; and then, just when I least expected it, Mr Brooke gave the order for the men to go to the boat.

He counter-ordered the men directly, and turned to me.

“These are pretty contemptible things to worry about, Herrick,” he said, “but unless we are well provisioned the men cannot fight. We must wait and take that food with us.”

Ching was communicated with, and declared the birds done. This announcement was followed by rolling them out, and, after they had cooled a bit, goose and duck were borne down to the boat in their clay shells, and stowed aft, ready for use when wanted.

Ten minutes later we were gliding once more through the darkness outward in the direction of the two junks, while my heart beat high in anticipation of my having to play a part in a very rash and dangerous proceeding—at least it seemed to be so to me.