Chapter 12 | In the Thick of it | A Dash From Diamond City

The report of the rifle was magical in its effect upon the Basuto ponies, each rearing up on its hind legs and striking out with its forefeet; but the same punishment was meted out by the riders—namely, a sharp tap between the ears with the barrels of the rifles—and the result was that beyond fidgeting they stood fairly still, while flash, flash, flash, three more shots were fired. The bullets whizzed by with their peculiar noise, sounding quite close, but probably nowhere near the riders—those who fired judging in the darkness quite by sound.

“Let’s keep on at a walk,” whispered West; but, low as his utterance was, the sound reached an enemy’s ears.

“Mind what you’re about!” said someone close at hand, evidently mistaking the speaker for a friend; “one of those bullets went pretty close to my ear. Whereabouts are they?”

“Away to the right,” whispered Ingleborough, in Dutch.

“Come on then,” said the former speaker. “Ck!”

The pony the man rode made a plunge as if spurs had been suddenly dug into its sides, and the dull beat of its hoofs on the dusty soil told of the course its rider was taking.

West was about to speak when the rapid beating of hoofs came from his left, and he had hard work to restrain his own mount from joining a party of at least a dozen of the enemy as they swept by noisily in the darkness.

“What do the fools think they are going to do by galloping about like that?” said Ingleborough gruffly.

“If they had kept still they might have caught us. Hallo! Firing again!”

Three or four shots rang out on the night air, and away in front of the pair the beating of hoofs was heard again.

“Why, the country seems alive with them,” whispered West. “Hadn’t we better keep on?”

“Yes, we must chance it,” was the reply. “No one can see us twenty yards away.”

“And we ought to make the most of the darkness.”

“Hist!” whispered Ingleborough, and his companion sat fast, listening to the movements of a mounted man who was evidently proceeding cautiously across their front from left to right. Then the dull sound of hoofs ceased—went on again—ceased once more for a time, so long that West felt that their inimical neighbour must have stolen away, leaving the coast quite clear.

He was about to say so to Ingleborough, but fortunately waited a little longer, and then started, for there was the impatient stamp of a horse, followed by a sound that suggested the angry jerking of a rein, for the animal plunged and was checked again.

As far as the listeners could make out, a mounted man was not forty yards away, and the perspiration stood out in great drops upon West’s brow as he waited for the discovery which he felt must be made. For a movement on the part of either of the ponies, or a check of the rein to keep them from stretching down their necks to graze, would have been enough. But they remained abnormally still, and at last, to the satisfaction and relief of both, the Boer vedette moved off at a trot, leaving the pair of listeners once more free to breathe.

“That was a narrow escape!” said West, as soon as their late companion was fairly out of hearing.

“Yes. I suppose we ought to have dismounted and crawled up to him and put a bullet through his body,” answered Ingleborough.

“Ugh! Don’t talk about it!” replied West. “I suppose we shall have plenty of such escapes as this before we have done.”

“You’re right! But we can move on now, and—Hist! There are some more on the left.”

“I don’t hear anyone. Yes, I do. Sit fast; there’s a strong party coming along.”

West was quite right, a body of what might have been a hundred going by them at a walk some eighty or ninety yards away, and at intervals a short sharp order was given in Boer-Dutch which suggested to West commands in connection with his own drill, “Right incline!” or “Left incline!” till the commando seemed to have passed right away out of hearing.

“Now then,” said West softly, “let’s get on while we have the chance.”

The words were hardly above his breath, but in the utter stillness of the night on the veldt they penetrated sufficiently far, and in an instant both the despatch-riders knew what the brief orders they had heard meant, namely that as the commando rode along a trooper was ordered to rein up at about every hundred yards and was left as a vedette.

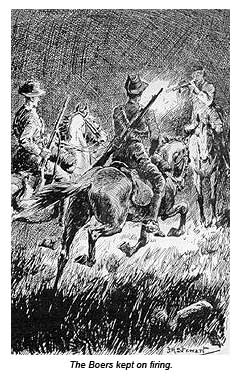

For no sooner had West spoken than there was a sharp challenge to left and right, running away along a line, and directly after the reports of rifles rang out and bullets whizzed like insects through the dark night air. Many flew around and over the heads of the fugitives; for the moment the discovery was made West and Ingleborough pressed their ponies’ sides and went forward at full gallop to pass through the fire in front of them.

It was close work, for guided by the sounds of  the ponies’ hoofs, the Boers kept on firing, one shot being from close at hand—so close that the flash seemed blinding, the report tremendous. This was followed by a sharp shock, the two companions, as they tore on, cannoning against the vedette, West’s pony striking the horse in his front full upon the shoulder and driving the poor beast right in the way of Ingleborough’s, with the consequence that there was a second collision which sent the Boer and his horse prostrate, Ingleborough’s pony making a bound which cleared the struggling pair, and then racing forward alongside of its stable companion, when they galloped on shoulder to shoulder. They were followed by a scattered fire of bullets, and when these ceased West turned in his saddle and listened, to hear the heavy beat of many hoofs, telling of pursuit; but the despatch-riders were well through the line, and galloped on at full speed for the next half-hour, when they slackened down and gradually drew rein and listened.

the ponies’ hoofs, the Boers kept on firing, one shot being from close at hand—so close that the flash seemed blinding, the report tremendous. This was followed by a sharp shock, the two companions, as they tore on, cannoning against the vedette, West’s pony striking the horse in his front full upon the shoulder and driving the poor beast right in the way of Ingleborough’s, with the consequence that there was a second collision which sent the Boer and his horse prostrate, Ingleborough’s pony making a bound which cleared the struggling pair, and then racing forward alongside of its stable companion, when they galloped on shoulder to shoulder. They were followed by a scattered fire of bullets, and when these ceased West turned in his saddle and listened, to hear the heavy beat of many hoofs, telling of pursuit; but the despatch-riders were well through the line, and galloped on at full speed for the next half-hour, when they slackened down and gradually drew rein and listened.

“Can’t hear a sound!” said West.

“Nor I,” replied Ingleborough, after a pause. “So now let’s breathe our nags and go steadily, for we may very likely come upon another of these lines of mounted men.”

A short consultation was then held respecting the line of route to be followed as likely to be the most clear of the enemy.

“I’ve been thinking,” said Ingleborough, “that our best way will be to strike off west, and after we are over the river to make a good long détour.”

West said nothing, but rode on by his companion’s side, letting his pony have a loose rein so that the sure-footed little beast could pick its way and avoid stones.

“I think that will be the best plan,” said Ingleborough, after a long pause.

Still West was silent.

“What is it?” said his companion impatiently.

“I was thinking,” was the reply.

“Well, you might say something,” continued Ingleborough, in an ill-used tone. “It would be more lively if you only gave a grunt.”

“Humph!”

It was as near an imitation as the utterer could give, and Ingleborough laughed.

“Thanks,” he said. “That’s a little more cheering. I’ve been thinking, too, that if we make this détour to the west we shall get into some rougher country, where we can lie up among the rocks of some kopje when it gets broad daylight.”

“And not go on during the day?”

“Certainly not; for two reasons: our horses could not keep on without rest, and we should certainly be seen by the Boers who are crowding over the Vaal.” West was silent again.

“Hang it all!” cried Ingleborough. “Not so much as a grunt now! Look here, can you propose a better plan?”

“I don’t know about better, but I was thinking quite differently from you.”

“Let’s have your way then.”

“Perhaps you had better not. You have had some experience in your rides out on excursions with Mr Norton, and I daresay your plan is a better one than mine.”

“I don’t know,” said Ingleborough shortly. “Let’s hear yours.”

“But—”

“Let’s—hear—yours,” cried the other imperatively, and his voice sounded so harsh that West felt annoyed, and he began:

“Well, I thought of doing what you propose at first.”

“Naturally: it seems the likeliest way.”

“But after turning it over in my mind it seemed to me that the Boers would all be hurrying across the border and scouring our country, looking in all directions as they descended towards Kimberley.”

“Yes, that’s right enough. But go on; don’t hesitate. It’s your expedition, and I’m only second.”

“So I thought that we should have a far better chance and be less likely to meet with interruption if we kept on the east side of the Vaal till it turned eastward, and then, if we could get across, go on north through the enemy’s country.”

“Invade the Transvaal with an army consisting of one officer and one man?”

“There!” cried West pettishly. “I felt sure that you would ridicule my plans.”

“Then you were all wrong, lad,” cried Ingleborough warmly, “for, so far from ridiculing your plans, I think them capital. There’s success in them from the very cheek of the idea—I beg your pardon: I ought to say audacity. Why, of course, if we can only keep clear of the wandering commandos—and I think we can if we travel only by night—we shall find that nearly everyone is over the border on the way to the siege of Kimberley, and when we stop at a farm, as we shall be obliged to for provisions, we shall only find women and children.”

“But they’ll give warning of our having been there on our way to Mafeking.”

“No, they will not. How will they know that we are going to Mafeking if we don’t tell them? I’m afraid we must make up a tale. Perhaps you’ll be best at that. I’m not clever at fibbing.”

“I don’t see that we need tell the people lies,” said West shortly.

“Then we will not,” said his companion. “Perhaps we shall not be asked; but if we are I shall say that we are going right away from the fighting because we neither of us want to kill any Boers.”

“Humph!” grunted West.

“What, doesn’t that suit you? It’s true enough. I don’t want to kill any Boers, and I’m sure you don’t. Why, when you come to think that we shall be telling this to women whose husbands, sons, or brothers have been commandoed, we are sure to be treated as friends.”

“We had better act on your plan,” said West, “and then we need make up no tales.”

“Wait a minute,” said Ingleborough. “Pull up.”

West obeyed, and their ponies began to nibble the herbage.

“Now listen: can you hear anything?”

West was silent for nearly a minute, passed in straining his ears to catch the slightest sound.

“Nothing,” he said at last.

“Nothing,” said his companion. “Let’s jump down!”

West followed his companion’s example, and swung himself out of the saddle.

“Now get between the nags’ heads and hold them still. You and they will form three sides of a square: I’m going to be the fourth.”

“What for?”

“To light a match.”

“Oh, don’t stop to smoke now,” said West reproachfully. “Let’s get on.”

“Who’s going to smoke, old Jump-at-conclusions? I’m going to carry out our plan.”

Scratch! and a match blazed up, revealing Ingleborough’s face as he bent down over it to examine something bright held in one hand—something he tried to keep steady till the match burned close to his fingers and was crushed out.

“Horses’ heads are now pointing due north,” he said. “Keep where you are till I’m mounted. That’s right! Now then, up you get! That’s right! Now then! Right face—forward!”

“But you’re going east.”

“Yes,” said Ingleborough, with a little laugh, “and I’m going with West or by West all the same. We must keep on till we get to the railway, cross it, and then get over the border as soon as we can.”

“What, follow out my plan?”

“Of course! It’s ten times better than mine. Look here, my dear boy, you are a deal too modest. Recollect that you are in command, and that my duty is to obey.”

“Nonsense!”

“Sense, sir; sound sense. I’ve got enough in my head to know when a thing’s good, and you may depend upon my opposing you if I feel that you are going to act foolishly. Once for all, your idea’s capital, lad; so let’s get on as fast as we can till daybreak, and then we can lie up in safely in the enemy’s country.”

In due course the railway was reached, a breeze springing up and sweeping the sky clear so that they had a better chance of avoiding obstacles in the way, and as soon as they were well over the line the ponies were kept at a canter, which was only checked here and there over broken ground. This, however, became more plentiful as the night glided away, but the rough land and low kopjes were the only difficulties that they encountered on the enemy’s side of the border, where they passed a farm or two, rousing barking dogs, which kept on baying till the fugitives were out of hearing.

At last the pale streak right in front warned them that daylight was coming on fast, and they searched the country as they cantered on till away more to the north a rugged eminence clearly seen against the sky suggested itself as the sort of spot they required, and they now hurried their ponies on till they came to a rushing, bubbling stream running in the right direction.

“Our guide, Noll,” said Ingleborough quietly; “that will lead us right up to the kopje, where we shall find a resting-place, a good spot for hiding, and plenty of water as well.”

All proved as Ingleborough had so lightly stated; but before they reached the shelter amongst the piled-up masses of granite and ironstone, with shady trees growing in the cracks and crevices, their glasses showed them quite half-a-dozen farms dotted about the plain. They were in great doubt as to whether they were unseen when they had to dismount and lead their willing steeds into a snug little amphitheatre surrounded by rocks and trees, while the hollow itself was rich with pasturage such as the horses loved best, growing upon both sides of the clear stream whose sources were high up among the rocks.

“You see to hobbling the ponies, Noll,” said Ingleborough, “while I get up as high as I can with my glass and give an eye to the farms. If we’ve been seen someone will soon be after us. We can’t rest till we know. But eat your breakfast, and I’ll nibble mine while I watch. Don’t take off the saddles and bridles.”

West did as he was requested, and ate sparingly while he watched the horses browsing for quite an hour, before Ingleborough came down from the highest part of the kopje.

“It’s all right,” he said. “Let’s have off the saddles and bridles now. Have you hobbled them well?”

“Look,” said West.

“Capital. I didn’t doubt you; but you might have made a mistake, and if we dropped asleep and woke up to find that the ponies were gone it would be fatal to your despatch.”

“Yes; but one of us must keep watch while the other sleeps.”

“It’s of no use to try, my lad. It isn’t to be done. If we’re going to get into Mafeking in a business-like condition we must have food and rest. Come, the horses will not straggle away from this beautiful moist grass, so let’s lie down in this shady cave with its soft sandy bottom and sleep hard till sunset. Then we must be up and away again.”

“But anxiety won’t let me sleep,” said West. “I’ll sit down and watch till you wake, and then I’ll have a short sleep while you take my place.”

“Very well,” said Ingleborough, smiling.

“What are you laughing at?” said West, frowning.

“I was only thinking that you had a very hard day yesterday and that you have had an arduous time riding through the night.”

“Yes, of course.”

“Well, nature is nature! Try and keep awake if you can! I’m going to lie flat on my back and sleep. You’ll follow my example in less than an hour.”

“I—will—not!” said West emphatically.

But he did, as he sat back resting his shoulders against the rock and gazing out from the mouth of the cave where they had made themselves comfortable at the beautiful sunlit veldt, till it all grew dark as if a veil had been drawn over his eyes.

It was only the lids which had closed, and then, perfectly unconscious, he sank over sidewise till he lay prone on the soft sand, sleeping heavily, till a hand was laid upon his shoulder and he started into wakefulness, to see that the sun had set, that the shadows were gathering over the veldt, and then that Ingleborough was smiling in his face.

“Rested, old man?” he said. “That’s right. The nags have had a splendid feed, and they are ready for their night’s work. I haven’t seen a soul stirring. Come on! Let’s have a good drink of water and a feed, and by that time we ought to be ready to start.”

“We ought to cross the Vaal before morning,” said West.

“I doubt it,” was the reply, “for it will be rather a job, as we shall find the enemy about there. If we get across to-morrow night we shall have done well.”

“But we shall never get to Mafeking like this.”

“It’s going to be a harder task than you thought for when you volunteered so lightly, my dear boy; but we’ve undertaken to do it, and do it we will. It isn’t a work of hours nor days. It may take us weeks. Come along! I’m hungry, and so are you.”

“But tell me,” said West, “how long have you been awake?”

“Not above a quarter of an hour. We must have sleep and rest as well as food. When we’ve had the last we shall be ready for anything through the night.”

And so it proved as they rode on properly refreshed, meeting with no adventure, but being startled by the barking roars of lions twice during the night, which came to an end as they reached a very similar kopje offering just such accommodation as they had met with on the previous morning.

“Hah!” said Ingleborough. “Just enough prog left for a rough breakfast. To-morrow we shall have to begin travelling by day, so as to pay a visit to some farm, for we can’t do as the nags do, eat grass when they can get it and nibble green shoots when they can’t. Now then, my dear Noll, the orders for to-day are: sleep beneath this projecting shelf.”

“But I say,” said West, a minute or so later, “is your rifle charged? You were wiping the barrels as we rode along.”

There was no reply, for Ingleborough was fast asleep, and West soon followed his example.