Chapter 9 | Four-Legged Help | A Dash From Diamond City

“Here, you two boys,” cried the director; “I’ve just heard of this wild project. Are you mad, West?”

“I hope not, sir.”

“But, my good lad, I really—I—that is—bless my soul! It’s very brave of you; but I don’t think I ought to let you go.”

“I heard you say, sir, that everyone ought to be ready to devote his life to the defence of the country.”

“Eh?” cried the director. “To be sure, yes, I did—in that speech I made to the volunteers; but then you’re not everybody, and—er—er—you see, what I said was in a speech, and sometimes one says more then than one quite means.”

“There’ll be no work doing in the office, sir,” said Ingleborough; “and I hope you will not place any obstacles in the way of our going.”

“Oh no, my dear boys! I feel that I must not; but I don’t like you to run such a terrible risk.”

“We must all run risks, sir,” said West gravely.

“And I beg your pardon: our time is up for seeing the Commandant,” said Ingleborough, referring to his watch.

“Yes, I heard you were to go to him,” said the director. “But it sounds very rash. There, go on, and come to me afterwards.”

They parted, and a few minutes later the young men were ushered into the Commandant’s room.

“Then you have not repented, my lads?” he said, smiling.

“No, sir,” replied West, speaking for both; “we are quite ready to go.”

“Then I must take you both at your word. But once more I give you both the opportunity to draw back if you like.”

“Thank you, sir,” replied West; “but if you will trust us we will take the despatch.”

“Very well,” said the Commandant, turning very stern and business-like. “Here is the despatch. It is a very small packet, and I leave it to your own ingenuity to dispose of it where it cannot be found if you have the bad luck to be captured. It must be sewn up in your pockets, or fitted into your hats, or hidden in some way or other. I leave it to you, only telling you to destroy it sooner than it should fall into the enemy’s hands.”

“We’ll consult together, sir, and decide what to do,” replied West, looking frankly in the officer’s eyes; “but—I have heard of such a thing being done, sir—”

“What do you mean?” said the Commandant sternly.

“That to ensure a despatch not falling into the enemy’s hands the bearer learned its contents carefully and then burned it.”

“Hah! Yes. That would make it safe,” cried the officer, with a satisfied look. “But, no, it could not be done in this case. I have no right to open the despatch, and I do not know its contents. You must take it as it is, and in the event of disaster burn or bury it. Destroy it somehow. It must not fall into the enemy’s hands. Here.”

“I understand, sir,” said West, taking the thick letter in its envelope, as it was extended to him; and the Commandant heaved a sigh as if of relief on being freed of a terrible incubus.

“There,” he said, “I shall tie you down to no restrictions other than these. That packet must somehow be placed in the hands of the Colonel Commandant at Mafeking. I do not like to name failure, for you are both young, strong, and evidently full of resource; but once more: if you are driven too hard, burn or destroy the packet. Now then, what do you want in the way of arms? You have your rifles, and you had better take revolvers, which you can have with ammunition from the military stores. Do you want money?”

“No, sir; we shall require no money to signify,” said Ingleborough quietly. “But we must have the best horses that can be obtained.”

“Those you must provide for yourselves. Take the pick of the place, and the order shall be made for payment. My advice is that you select as good a pair of Basuto ponies as you can obtain. They will be the best for your purpose. There, I have no more to say but ‘God speed you,’ for it is a matter of life and death.”

He shook hands warmly with both, and, on glancing back as soon as they were outside, they saw the Commandant watching them from the window, whence he waved his hand.

“He thinks we shall never get back again, Noll,” said Ingleborough, smiling; “but we’ll deceive him. Now then, what next?”

“We must see Mr Allan,” replied West.

“Then forward,” cried Ingleborough. “We must see old Norton too before we go, or he’ll feel huffed. Let’s go round by his place.”

They found the superintendent in and ready to shake hands with them both warmly.

“Most plucky!” he kept on saying. “Wish I could go with you.”

“I wish you could, and with a hundred of your men to back us up,” said West laughingly.

“You ought to have a couple of thousand to do any good!” said the superintendent: “but even they would not ensure your delivering your despatch. By rights there ought to be only one of you. That would increase your chance. But it would be lonely work. What can I do for you before you go?”

“Only come and see us off this evening.”

“I will,” was the reply, “and wish you safe back.”

“And, I say,” said Ingleborough: “keep your eye on that scoundrel.”

“Anson? Oh yes: trust me! I haven’t done with that gentleman yet.”

Directly after they were on their way to the director’s room, and as they neared the door they could hear him pacing impatiently up and down as if suffering from extreme anxiety.

The step ceased as they reached and gave a tap at the door, and Mr Allan opened to them himself.

“Well,” he said, “has the Commandant decided to send you?”

“Yes, sir,” replied West.

“I’m very sorry, and I’m very glad; for it must be done, and I know no one more likely to get through the Boer lines than you two. Look here, you’ll want money. Take these. No questions, no hesitation, my lads; buckle on the belts beneath your waistcoats. Money is the sinews of war, and you are going where you will want sinews and bones, bones and sinews too.”

In his eagerness the director helped the young men to buckle on the two cash-belts he had given them.

“There,” he said; “that is all I can do for you but wish you good luck. By the time you come back we shall have sent the Boers to the right-about, unless they have captured Kimberley and seized the diamond-mines. Then, of course, my occupation will be gone. Goodbye. Not hard-hearted, my boys; but rather disposed to be soft. There, goodbye.”

“Now then,” said West, “we’ve no time to spare. What are we going to do about horses?”

“We’ve the money at our back,” replied Ingleborough, “and that will do anything. We are on Government service too, so that if we cannot pay we can pick out what we like and then report to headquarters, when they will be requisitioned.”

But the task proved easy enough, for they had not gone far in the direction of the mines when they met another of the directors, who greeted them both warmly.

“I’ve heard all about it, my lads,” he said, “and it’s very brave of you both.”

“Please don’t say that any more, sir,” cried West appealingly, “for all we have done yet is talk. If we do get the despatch through there will be some praise earned, but at present we’ve done nothing.”

“And we’re both dreadfully modest, sir,” said Ingleborough.

“Bah! you’re not great girls,” cried the director. “But you are not off yet, and you can’t walk.”

“No, sir,” said West; “we are in search of horses—good ones that we can trust to hold out.”

“Very well; why don’t you go to someone who has been buying up horses for our mounted men?”

“Because we don’t know of any such person,” said West. “Do you?”

“To be sure I do, my lad, and here he is.”

“You, sir?” cried Ingleborough excitedly. “Why, of course; I heard that you were, and forgot in all the bustle and excitement of the coming siege. Then you can let us have two? The Commandant will give an order for the payment.”

“Hang the Commandant’s payments!” cried the director testily. “When young fellows like you are ready to give their lives in the Queen’s service, do you think men like we are can’t afford to mount them? Come along with me, and you shall have the pick of the sturdy cob ponies I have. They’re rough, and almost unbroken—what sort of horsemen are you?”

“Very bad, sir,” replied Ingleborough: “no style at all. We ride astride though.”

“Well, so I suppose,” said the director, laughing, “and with your faces to the nag’s head. If you tell me you look towards the tail I shall not believe you. But seriously, can you stick on a horse tightly when at full gallop?”

“Oliver West can, sir,” replied Ingleborough. “He’s a regular centaur foal.”

“Nonsense! Don’t flatter,” cried West. “I can ride a bit, sir; but Ingleborough rides as if he were part of a horse. He’s accustomed to taking long rides across the veldt every morning.”

“Oh, we can ride, sir,” said Ingleborough coolly; “but whether we can ride well enough to distance the Boers has to be proved.”

“I’ll mount you, my boys, on such a pair of ponies as the Boers haven’t amongst them,” said the director warmly. “Do you know my stables—the rough ones and enclosure I have had made?”

“We heard something about the new stabling near the mine, sir,” said West; “but we’ve been too busy to pay much heed.”

“Come and pay heed now, then.”

The speaker led the way towards the great mine buildings, and halted at a gate in a newly set-up fence of corrugated-iron, passing through which their eyes were gladdened by the sight of about a dozen of the rough, sturdy little cobs bred by the Basutos across country, and evidently under the charge of a couple of Kaffirs, who came hurrying up at the sight of their “baas,” as they termed him.

Here Ingleborough soon displayed the knowledge he had picked up in connection with horses by selecting two clever-looking muscular little steeds, full of spirit and go, but quite ready to prove how little they had been broken in, and promising plenty of work to their riders if they expected to keep in their saddles.

“Be too fresh for you?” said the owner.

“We shall soon take the freshness out of them, poor things!” said Ingleborough. “Would you mind having them bridled and saddled, sir?”

The order was given, and, after a good deal of trouble and narrowly escaping being kicked, the Kaffirs brought the pair selected up to where the despatch-riders were standing with the director.

Ingleborough smiled, and then bade the two Kaffirs to stand on the far side of the ponies, which began to resent the Kaffirs’ flank movements by sidling up towards the two young men.

“Ready?” said Ingleborough, in a low, sharp tone.

“Yes.”

“Mount!”

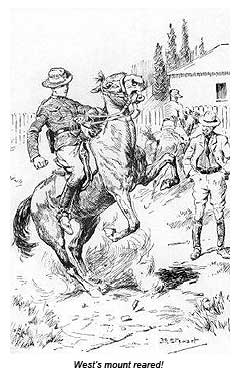

They both sprang into their saddles, to the intense astonishment of the ponies, one of which made a bound and dashed off round the enclosure at full speed, while the other, upon which West was mounted, reared straight up, and, preserving its balance upon its hind legs, kept on snorting, while it sparred out with its fore hoofs as if striking at some imaginary enemy, till the rider brought his hand down heavily upon the restive beast’s neck. The blow acted like magic, for the pony dropped on all-fours directly, gave itself a shake as if to rid itself of saddle and rider, and then  uttered a loud neigh which brought its galloping companion alongside.

uttered a loud neigh which brought its galloping companion alongside.

“Humph!” ejaculated their new friend; “I needn’t trouble myself about your being able to manage your horses, my lads. Will these do?”

“Splendidly, sir,” cried West.

“There they are, then, at your service!” And, after a few directions to the Kaffirs about having them ready when wanted, the party left the enclosure and separated with a few friendly words, the despatch-bearers making once more for the Commandant’s quarters to report what they had done so far, and to obtain a pass which would ensure them a ready passage through the lines and by the outposts.

They were soon ushered into the Commandant’s presence, and he nodded his satisfaction with the report of their proceedings before taking up a pen and writing a few lines upon an official sheet of paper.

“That will clear you both going and returning,” said he, folding and handing the permit. “Now then, when do you start?”

“Directly, sir,” said Ingleborough, who was the one addressed.

“No,” said the Commandant. “You must wait a few hours. Of course it is important that the despatch be delivered as soon as possible; but you must lose time sooner than run risks. If you go now, you will be seen by the enemy and be having your horses shot down—perhaps share their fate. So be cautious, and now once more goodbye, my lads. I shall look forward to seeing you back with an answering despatch.”

This was their dismissal, and they hurried away to have another look to their horses, and to see that they were well-fed, before obtaining a meal for themselves and a supply of food to store in their haversacks.

“There’s nothing like a bit of foresight,” said Ingleborough. “We must eat, and going in search of food may mean capture and the failure of our mission.”

The time was gliding rapidly on, the more quickly to West from the state of excitement he was in; but the only important thing he could afterwards remember was that twice over they ran against Anson, who seemed to be watching their actions, and the second time West drew his companion’s attention to the fact.

“Wants to see us off,” said Ingleborough. “I shouldn’t be surprised when we come back to find that he has eluded Norton and gone.”

“Where?” said West.

“Oh, he’ll feel that his chance here is completely gone, and he’ll make for the Cape and take passage for England.”

“If the Boers do not stop him.”

“Of course,” replied Ingleborough. “It’s my impression that he has smuggled a lot of diamonds, though we couldn’t bring it home to him.”

“I suppose it’s possible,” said West thoughtfully. “But isn’t it likely that he may make his way over to the enemy?”

Ingleborough looked at the speaker sharply.

“That’s not a bad idea of yours,” he said slowly; “but, if he does and he is afterwards caught, things might go very awkwardly for his lordship, and that flute of his will be for sale.”

“Flute for sale? What do you mean? From poverty?—no one would employ him. Oh! I understand now. Horrible! You don’t think our people would shoot him?”

“Perhaps not,” said Ingleborough coldly; “but they’d treat him as a rebel and a spy. But there, it’s pretty well time we started. Come along.”

Within half an hour they were mounted and off on their perilous journey, passing outpost after outpost and having to make good use of their pass, till, just as it was getting dusk, they parted from an officer who rode out with them towards the Boers’ encircling lines.

“There,” he said, “you’ve got the enemy before you, and you’d better give me your pass.”

“Why?” said West sharply.

“Because it has been a source of protection so far: the next time you are challenged it will be a danger.”

“Of course,” said Ingleborough. “Give it up, Oliver.”

“Or destroy it,” said the officer carelessly: “either will do.”

“Thanks for the advice,” said West, and they shook hands and parted, the officer riding back to join his men.

“You made him huffy by being suspicious,” said Ingleborough.

“I’m sorry, but one can’t help being suspicious of everything and everybody at a time like this. What do you say about destroying the Commandant’s pass?”

“I’m divided in my opinion.”

“So am I,” said West. “One moment I think it best: the next I am for keeping it in case we fall into the hands of some of our own party. On the whole, I think we had better keep it and hide it. Let’s keep it till we are in danger.”

“Chance it?” said Ingleborough laconically. “Very well; only don’t leave it till it is too late.”

“I’ll mind,” said West, and, as they rode out over the open veldt and into the gloom of the falling night, they kept a sharp look-out till they had to trust more to their ears for notice of danger, taking care to speak only in a whisper, knowing as they did that at any moment they might receive a challenge from the foe.

“What are you doing?” said Ingleborough suddenly, after trying to make out what his companion was doing. “Not going to eat yet, surely?”

“No—only preparing for the time when I must. Look here.”

“Too dark,” said Ingleborough, leaning towards his companion.

“Very well, then, I’ll tell you: I’m making a sandwich.”

“Absurd! What for?”

“I’ll tell you. You can’t see, but this is what I’m doing. I’ve two slices of bread here, and I’m putting between them something that is not good food for Boers. That’s it. I’ve doubled the pass in half, and stuck it between two slices. If we have the bad luck to be taken prisoners I shall be very hungry, and begin eating the sandwich and the pass. I don’t suppose it will do me any harm.”

“Capital idea,” said Ingleborough, laughing.

“That’s done,” said West, replacing his paper sandwich in his haversack, and a few minutes later, as they still rode slowly on, Ingleborough spoke again.

“What now?” he said.

“Making another sandwich,” was the reply.

“Another?”

“Yes, of the Mafeking despatch.”

“Ah, of course; but you will not eat that?”

“Only in the last extremity.”

“Good,” said Ingleborough, “and I hope we shall have no last extremes.”

He had hardly spoken when a sharp challenge in Boer-Dutch rang out, apparently from about fifty yards to their left, and, as if in obedience to the demand, the two Basuto ponies the young men rode stopped suddenly.

Ingleborough leaned down sidewise and placed his lips close to his companion’s ear.

“Which is it to be?” he said. “One is as easy as the other—forward or back?”

“One’s as safe as the other,” replied West, under his breath. “Forward.”

They were in the act of pressing their horses’ sides to urge them on when there was a flash of light from the position of the man who had uttered the challenge, and almost immediately the humming, buzzing sound as of a large beetle whizzing by them in its nocturnal flight, and at the same moment there was the sharp crack of a rifle.