Chapter 27 | Night on the Veldt | A Dash From Diamond City

The Kaffir grunted, and began what Ingleborough afterwards called “chuntering,” but he obeyed at once, leading the ponies at a quick walk in and out amongst several ostrich enclosures, till they were quite a quarter of a mile from the farm, from which there came the buzz of voices and the occasional stamp of a horse on the still night air.

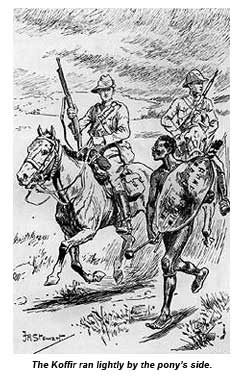

“No more wire fence!” said their guide, and indicating that they should urge the ponies forward he took his shield and spears from Ingleborough, caught hold of the mane of West’s pony, and then as they broke into a canter, ran lightly by the animal’s side, talking softly, and now and then breaking out into a merry laugh.

“Ought burn Tant’ Ann!” he said. “Wicked old witch! Very fat! Make her good vrouw!”

“I’m afraid Jack’s morals are sadly in need of improvement, lad,” said Ingleborough at last.

“What a horrible idea!” replied West, with a shudder; “and the worst of it is that the fellow seems to consider that it would have been a good piece of fun.”

“Yes, it is his nature to, as we are told of the bears and lions in the poems of Dr Watts. I dare say the old woman had been a horrible tyrant to the poor fellow!”

“But the hideous revenge!”

“Which hasn’t come off, my lad! But the black scoundrel’s ideas are shocking in the extreme, and I would not associate with him much in the future. Here! Hi! Olebo, stop!”

The young man drew rein, and the black looked up enquiringly.

“Lie down and listen for the Boers!”

The Kaffir nodded, and trotted a dozen yards away from the side of the ponies, threw himself down, listened, jumped up, and repeated the performance three times at greater distances before returning.

“No hear!” he said. “Gone other way.”

“It would be safe then to strike a match and look at the compass,” suggested West, and, taking out his box, he struck a light, shaded it in his slouch hat, and then held the little pocket compass to it.

“Well, which way are we going?”

“Due east.”

“Then we’ll turn due north, and travel that way till to-morrow night, and see what that brings forth.”

Starting off again, they journeyed on, sometimes at a walk, sometimes at an easy canter, so as to save the horses as much as possible, while the Kaffir kept up, seeming not in the slightest degree distressed, but ready to enter into conversation at any time, after changing from one side to the other so as to hold on by a different hand.

“Soon be daylight now,” said West; “but I hope this fellow does not expect to keep on with us, does he?”

“Oh no, I don’t think so for a moment. We’ll pull up before sunrise at some sheltered place and have a good look-out for danger before letting the ponies graze and having breakfast. Let’s see what happens then!”

But the sun was well up before a suitable kopje came in sight, one so small that it did not appear likely to contain enemies, but sufficiently elevated to give an observer a good view for miles through the clear veldt air.

“Looks safe!” said Ingleborough; “but burnt English children fear the Boer fire. Let’s have a good circle round.”

This was begun, and the black instantly grasped what was intended, and hanging well down from West’s stirrup-leather, he began to search the ground carefully for tracks, looking up from time to time and pointing out those of antelopes, lions, and ostriches, but never the hoof of horse or the footprint of man.

“No Boer there!” he said. “No one come. Good water,” he continued, pointing to the slight tracts of grass which had sprung up where a stream rising among the rocks was losing itself in the dry soil, but which looked brighter and greener as it was nearer to the kopje, which was fairly furnished with thorn-bush and decent-sized trees.

“Any Boers hiding there?” said West sharply.

“Boers ride there on ponies!” replied the Kaffir decisively, as he pointed down at the drab dust. “No ponies make marks.”

“That’s enough,” said Ingleborough. “Come along.”

Without hesitation now they put their mounts to a canter, rode up to the pleasant refreshing-looking place, and after leaving the ponies with the Kaffir and climbing to one of the highest points, took a good look round. This proved that there was not a mounted man in sight, and they descended to select a spot where there was plenty of herbage and water for their steeds, when they sat down and began to breakfast.

“Nothing like a fine appetite,” said West, after they had been eating for some little time; “but this biltong is rather like eating a leg of mahogany dining-table into which a good deal of salt gravy and furniture oil has been allowed to soak.”

“Yes, it is rather wooden,” said Ingleborough coolly. “Must wear out a man’s teeth a good deal.”

“Eland,” said the Kaffir, tapping his stick of the dried meat on seeing his companions examining and smelling the food. “Old baas shoot eland, Olebo cut him up and dry him in the sun. Good.”

“Well, it isn’t bad, O child of nature! But I say, how far do you mean to come with us?”

“No go any more,” replied the man. “Go Olebo kraal, see wife. Give her big shilling and little yellow shilling.—Good?”

He brought out the sovereign from where it had been placed, and held it up.

“Good? Yes,” said West, and he set to work to try and explain by making the black bring out a florin and then holding up his outspread ten fingers, when the man seemed to have some idea of his meaning.

“Look here, I’ll get it into his benighted intellect; but I should have thought that he would have known what a sovereign was worth.”

Just then the Kaffir nodded sharply, after examining the coin.

“Gold?” he said, in Dutch.

“Of course,” said Ingleborough, taking out a sovereign and ten more florins, which he placed in a heap and at a short distance from the little pile he laid down the sovereign. “Look here, Olebo,” he said, taking up the ten florins. “Buy four blankets!”

The Kaffir nodded, and his instructor replaced the heavy coins in his pocket to take up the sovereign.

“Now, see here,” said Ingleborough, holding it out. “Buy four blankets.”

“Ah!” cried the delighted black, snatching out his own treasured coins, the gold in one hand, the silver in the other. “Buy four blankets for Olebo wife,” he cried, holding forward the silver. Then putting it behind him he held out the sovereign: “Buy four blankets for Olebo.”

“Now we’ve got it,” cried West, laughing, and watching the way in which the black hid his cash away. “I say,” he continued, to his companion, speaking in English, “where does he put that money to keep it safe?”

“I dunno,” said Ingleborough. “It seems to come natural to these Kaffirs to hide away their treasures cunningly. See how artful they are over the diamonds! He doesn’t put the cash in his trousers pockets, nor yet in his waistcoat, nor yet his coat, because he has neither one nor the other. I expect he has a little snake-skin bag somewhere inside his leather-loincloth. But here, I’m thirsty; let’s have some water!”

As he spoke Ingleborough sprang up and walked towards the head of the spruit, followed by his companions, and they passed the two ponies, which were hard at work on the rich green herbage along the border of the stream. Then, getting well ahead of them, all lay down and thoroughly quenched their thirst.

“Now,” said West, “what next? We ought to go on at once,” and he unconsciously laid his hand upon the spot where the despatch was hidden.

“No,” replied Ingleborough, “that won’t do. We seem safe here, and we must hasten slowly. We’re ready enough to go on, but the ponies must be properly nursed. They want more grass and a rest.”

“The sun is getting hot too,” said West, in acknowledgment of his comrade’s words of wisdom.

“We’ll stop till evening, lad,” continued Ingleborough, “and take it in turn to sleep in the shade of those bushes if we can find a soft spot. We had no rest last night.”

“I suppose that must be it,” replied West, and he joined in a sigh on finding a satisfactory spot beneath a mass of granite from which overhung a quantity of thorn-bush and creeper which formed an impenetrable shade.

The black followed them, noting keenly every movement and trying hard to gather the meaning of the English words.

“Two baas lie down long time, go to sleep,” he said at last, in broken Dutch. “Olebo sit and look, see if Boer come. See Boer, make baas wake up.”

“No,” said West; “you two lie down and sleep. I’ll take the first watch.”

Ingleborough made no opposition, and after West had climbed up to a spot beneath a tree from which he could get a good stretch of the veldt in view, the others lay down at once and did not stir a limb till West stepped down to them, when the Kaffir sprang up without awakening Ingleborough.

“Olebo look for Boers now,” he said.

West hesitated, and the Kaffir grasped the meaning of his silence.

“Olebo come and tell baas when big old baas go to fetch Boers,” he said.

“So you did,” cried the young Englishman warmly, “and I’ll trust you now. Mind the ponies don’t stray away.”

The black showed his beautiful, white teeth in a happy satisfied laugh.

“Too much grass, too much nice water,” he said. “Basuto pony don’t go away from baas only to find grass.”

“You’re right!” said West. “Wait till the sun is there!” he continued, pointing to where it would be about two hours after mid-day, “and then wake the other baas.”

The Kaffir nodded, and West lay down to rest, as he put it to himself, for he was convinced that he would be unable to sleep; but he had not lain back five minutes, gazing at the sunlit rivulet and the ponies grazing, before his lids closed and all was nothingness till he was roused by a touch from Ingleborough.

The sun was just dipping like a huge orange ball in the vermilion and golden west.

“Had a good nap, old fellow?”

“Oh, it’s wonderful!” said the young man, springing up. “I don’t seem to have been asleep five minutes.”

“I suppose not. Well, all’s right, and Blackjack is waiting to say good-bye. He wants to start off home.”

The Kaffir came up from where he had been patting and caressing the ponies, and stood looking at them as motionless in the ruddy evening light as a great bronze image.

“Olebo go now,” he said, turning his shield to show that the remains of his share of the provisions were secured to the handle by a rough net of freshly-plaited grassy rush. “Olebo see baas, both baas, some day.” He accompanied the words with a wistful look at each, and before they could think of what to say in reply he turned himself sharply and ran off at a rapid rate, getting out of sight as quickly as he could by keeping close to the bushes, before striking out into the veldt.

“Humph! I suppose they are treacherous savages, some of them,” said Ingleborough thoughtfully; “but there doesn’t seem to be much harm in that fellow if he were used well.”

“I believe he’d make a very faithful servant,” said West sadly. “I’m beginning to be sorry we let him go.”

“So am I. We shall feel quite lonely without him. But the despatch.”

“Ah, yes, the despatch!” said West, pulling himself together. “Now then, boot and saddle, and a long night’s ride!”

“And a good day’s rest afterwards! That’s the way we must get on.”

A quarter of an hour after, they had taken their bearings by compass and mounted, when the well-refreshed ponies started off at once in a brisk canter, necessitating the drawing of the rein from time to time; and then it was on, on, on at different rates beneath the wonderfully bright stars of a glorious night, during which they passed several farms and one good-sized village, which were carefully avoided, for they had enough provisions to last them for another day, and naturally if a halt was to be made to purchase more it would have to be at a seasonable time.

“Yes,” said Ingleborough laughingly, “it would be a sure way of getting cartridges if we wanted them and roused up a Boer farmer in the night. He would soon give us some, the wrong way on.”

“Yes,” said West, “and there would be the dogs to deal with as well. Hark at that deep-mouthed brute!”

For just then the cantering of their ponies had been heard by the watch-dog at one of the farms, and it went on baying at them till the sounds grew faint.

Then it was on and on again till a strange feeling of weariness began to oppress them, and they had to fight with the desire which made them bend forward and nod over their ponies’ necks, rising up again with a dislocating start.

At the second time of this performance West made a great effort and began watching his companion, to see that he was just as bad. Then the intense desire to sleep began to master the watcher again.

“Hi, Ingle!” he cried. “Rouse up, and let’s walk for a mile or two.”

“Yes, yes.—What’s that?” cried Ingleborough, springing off his pony and cocking his rifle.

For there was a sudden rushing noise as of a great crowd of animals, of what kind it was still too dark to see; but it was evident that they had come suddenly upon a migratory herd of the graceful-limbed antelopes that had probably been grazing and had been startled into flight.

“Pity it was not light!” said Ingleborough, with a sigh. “We could have got some fresh meat, and then at the first patch of wood and pool of water we could have had a fire and frizzled antelope-steaks.”

But a couple of hours later, when they halted for their rest and refreshment, it was stale cake, hard biltong, and cool fresh water.

“Never mind, we’re miles nearer Mafeking!” said West. “How many more nights will it take?”

The answer to that question had not been arrived at when they dropped asleep, lulled by the sound of rippling water and the crop, crop, crop made by the grazing ponies, and this time their weariness was so great that sleep overcame them both. Ingleborough was to have watched, but nature was too strong, and both slept till sundown, to rise up full of a feeling of self-reproach.